Upstream Color is the new movie by the writer/director Shane Carruth, whose last, and first, movie, Primer, came out back in ’04. Primer is an odd, unique movie about time travel. Upstream Color is a very different, much more complex and intriguing movie about many things, with different viewers coming away with very different interpretations. I saw it a few weeks ago and wrote it up here. I liked it a lot.

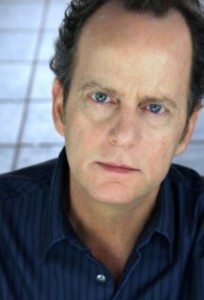

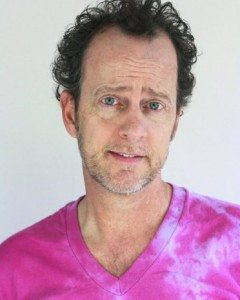

Though the leads in the movie are played by Carruth and Amy Seimetz, the strangest and most oblique character, known as The Sampler, is played by Andrew Sensenig, who in the past decade has been in more movies than you can shake a stick at. I’m not sure why you would spend your time shaking sticks at movies, but that’s a discussion for another time.

Andrew was kind enough to talk to us about his work in Upstream Color, which opens today in New York, and everywhere else in the weeks to follow. Check it out, folks. You’ve never seen anything quite like it. Love it or find it baffling, it’ll give you plenty to think and talk about.

Sean McPharlin: Thanks for taking the time to talk, Andrew. How did you come to be involved with Upstream Color?

Andrew Sensenig: I’m based in Dallas, and spend most of my time traveling for film work. Through the grapevine I heard that Shane Carruth was starting up a new film that was shooting in Dallas. I had seen Primer many times and was interested in anything Shane was doing. I did a little networking and got in touch with producer Ben LeClair, who got me the script. I read it in one sitting. It reads like the finished film. Once the energy gets moving you can’t pull away. I told Ben I was very interested, and set up a meeting with Shane, which was fantastic. We seemed to see eye to eye. I felt like I knew exactly where he wanted to go. I put a few scenes on tape, and Ben called and said they weren’t going to audition anyone else. I said I was on board.

SM: Watching the movie, it felt like it was both made with a very clear intention of what it was supposed to be, and that it was nevertheless found in the editing. Did you feel the movie changed much from script to the final film?

AS: Shane made adjustments as we moved through the production, such as writing new music. The final result wasn’t what he was expecting six months earlier, but the main story was there, the individual narratives and exploring humanity down to a very basic scientific level. He explores it down to the smallest microbe.

Shane gives a lot of credit to editor David Lowery for his work on the edit. David is a genius who really understood the story. Shane was shooting hours and days of footage, and so it wasn’t until he and David sat down together to edit it that the story really fell out. It then became clear what kind of pacing was required, the very quick editing. It’s almost like a class in editing, where you come into the scenes as late as possible, and leave as early as possible. It really keeps you wondering what’s happening, and asking things like, “Why is there a pig farmer?”

SM: Your character, The Sampler AKA the pig farmer, reminded me (and the reviewer for the NYT, I noted today) of Bruno Ganz’s angel in Wim Winders’s Wings of Desire. Did that ever occur to you or Shane?

AS: Someone else said that me too, but I’ve never seen the film. I had to look it up. I didn’t know anything about it. The Sampler is so fun to play because it’s one of those roles that people are still debating, depending on where they come from in life. They’re trying to figure out who this guy is, and what his role in the story is.

SM: It’s not easy to say. I liked how the basic cause and effect of the movie was ultimately easy to put together–in terms of what is actually happening, it’s essentially clear by the end–and yet what those events mean is completely open to interpretation.

AS: That’s right. If you sit and watch it, the storyline makes perfect sense. But then you walk away thinking, gosh, why did that happen? Does that really happen? Am I being controlled right now? Are we too caught up in a cycle? Everyone I talk to views the sense of control in the film differently. I’ve had people say my character is the villian, or that my character is the good guy, or that he’s a kind of Shakespearean tragic figure. People’s different ways of looking at the world inform how they look at the character, and at the meaning of the movie.

Is The Sampler’s tending of the pigs influencing events? Does he realize that the piglets create the worms? Or does he not know about that aspect? That’s where Shane was going. He created a triangle: The Sampler, The Thief, and the orchids. The Thief does his job, The Sampler does his job, the orchids do their job, and all of that creates a cycle that goes on for however many eons. Finally you get a person, Kris (Amy Seimetz), who figures it out and is able to break the cycle.

SM: Do you know if Shane has a role for you in his next movie, Modern Ocean?

AS: I don’t know. He’s been swamped promoting Upstream Color. It’s like a concert tour, rolling out the film, self-releasing it. The response has been greater than anyone anticipated. Shane was very determined, but didn’t know there’d be this much of a reaction.

But yes, I would love to work on Modern Ocean. We talked about it while shooting Upstream Color, and it sounds great. I’ll work for him any time.

SM: Why the decision to self-release?

AS: He decided to self-release because at the end of the day, even if the film doesn’t gross as much as it would have through using a normal distributor, Shane will make much more money because he controls it. Shane wants to make more films—more of his own films—and every penny he makes on this one he’ll put into the next.

SM: You did a lot of theater and other creative work when you were younger, then stopped, and only returned to acting recently. What brought that about?

AS: Growing up I trained in music and theater, and went to college in theater. I had grand dreams. Then I fell in love with my wife, had children, and decided to be more responsible and entrepreneurial, working in the business world, a family man. Then when my daughter turned sixteen, my wife said, “You put your dream on hold. Time to get back out there.” So I jumped back in at age 46.

It’s been very, very good. I can’t complain. I still live in Dallas, so I don’t have to deal with the hustle and bustle of L.A., and I’ve continued to work. I’ve been very lucky. But you also have to be self-motivated. It can be hard getting up in the morning and doing all of those auditions. But the rewards come through in the end.

I see my job as trying to help someone like Shane bring a two-dimensional story into a three-dimensional one. I’m not there to give my opinion or walk the red carpet. My job is to help writers and directors bring their stories to life. I get so much joy out of doing that, out of watching their faces at the end of a scene and hearing them say, “That’s what I saw when I was writing this.”

It’s amazing to take this three-dimensional object and touch people you’ve never even met. There’s someone in New York right now watching Upstream Color and The Sampler will in some way touch them. It may not be in a good way, but they’ll talk about it. It’s great to have the opportunity to work with Shane and be a part of that, where the end result encourages people to talk. It’s crazy to think that’s what you want to do for a living!

SM: Do you have a particular method for choosing roles? Are you looking for work that inspires you, or taking what comes your way, or seeking out certain filmmakers, like with Shane?

AS: All of the above. I’m always happy to work. The work is the creative and collaborative process. In terms of looking for roles, I like to go about taking on challenging roles. In general, roles that aren’t what you do in normal life. I’ve had the luxury of doing doing physical comedy to deep, dark, demented thrillers. There’s no one that I prefer. It goes back to the desire to be part of the life of the story.

SM: Any actors that have particulary inspired you along the way, or when you were younger?

AS: A lot of the usual names, DeNiro, Pacino, Hoffman, my acting heroes when I was growing up. Three today I’d love to work with are William H. Macy, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Edward Norton.

There’s no acting technique that I push towards. My own work is always just 100 percent from within. Quite often a whole backstory doesn’t matter, all you are living is that one moment, right now. On the screen, sometimes actors put too much emphasis on the 30 years that led up to that moment. As a viewer I want to be caught up in the moment.

SM: The overuse of backstory is something that drives me crazy. What I find fascinating is someone doing something. I don’t need to know about that thing that happened to them when they were ten to be interested in them now.

AS: Somebody might have two lines, but still they want to discuss with the director the drug addiction their character overcame, and all the director wants is for them to open that door and say, “Good morning.”

Shane’s work is so up close and personal that you just get it. Amy’s performance doesn’t need any backstory, because everything happening to her is brand new. Everything is changed. Someone can say that she grew up somewhere, had a relationship, and so on, but it doesn’t matter. What matters is what she’s doing at the moment, which is all new. Amy is an incredible presence. She can take one moment and tell you a thousand things that have nothing to do with backstory.

SM: I used to always ask people what their favorite movie was. But that made them feel pressured to come up with a “good” answer. So now I ask this, because it’s merely a factual question: what movie have you seen more times than any other?

AS: [Laughs] You’re going to like this—Dumb And Dumber. Because it’s pure entertainment. You just laugh. Two characters who take on the world in their own way without any worries about who cares, or what someone thinks of them. It’s refreshing that they can have an outlook on life that’s dumb, and not care.

And the other one is Magnolia. That’s one that grabs all the senses. To me it’s somewhat like Upstream Color, where I continue to be transfixed every time I watch it, with multiple stories intertwining, just like in life, where all of our stories interconnect. Paul Thomas Anderson made the film in a way where the music moves through the stories, where he keeps the music singular, so you as a viewer are never allowed to leave the scene. Typically you cut to a new story and the music changes and you get to disengage.

Upstream Color is similar. Through many edits Shane keeps the music going throughout. The scenes are changing, but they’re all interconnected. You might be looking at the pigs and then the characters, but the musical thread forces us to stay with it. It makes it so we can’t leave the film.

SM: I agree. Upstream Color exerts an hypnotic effect.

AS: It’s a beautiful film and an important film. And the discussion that comes from it is more valuable than the film itself. It forces people to reflect on life and human connection and control. Some think it deals with fate, some with addiction. The fact that it can draw so many interpretations and make people talk is what makes it so powerful. That’s the effect Shane wanted to create.

SM: I think he did a great job. I hope people see this movie. Thanks so much for taking the time to talk, Andrew.

Upstream Color is out there, folks. Support independent cinema and see it!

Tomorrow morning I’m going to try for the third time to understand the story. I’m wanting so very much to fully grasp what’s going on.

Gary

cw3riedel@gmail.com

It’s fully comprehensible emotionally, IMO Gary. On a logical/story level, the film is deliberately open to interpretation.