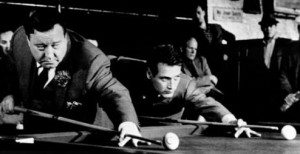

In the brilliant ’61 melodrama The Hustler, Paul Newman plays Fast Eddie Felson, basically a punk kid looking to make it big by playing and beating Minnesota Fats at straight pool (which if you’re wondering is played by sinking balls regardless of color or number, scoring one point per ball, and re-racking after the last ball is sunk, a player shooting till he misses, rack after rack, hour after hour, until reaching an agreed upon score or someone concedes defeat). But pool is only the background for most of the movie, which is centered on Eddie’s relationships to his old partner and a new girlfriend he treats miserably, which leads to tragedy, which leads to Eddie coming to terms with who he is and what he’s done, which leads to him playing and beating Fats, which leads to his being black-listed from big-time pool. What it is to win and what it is to lose is not as obvious as it seems in The Hustler.

Twenty-five years later Martin Scorsese made The Color of Money, a rare thing, a great sequel, and the thing about The Color of Money is that the opening scene is a perfect, beautiful showcase, in a way rarely seen today, of what let’s call the language of cinema. Everything you need to know about writing, directing, and editing a movie you can learn watching this one scene.

What I mean by “the language of cinema” is the use of dialogue, framing, camera movement, editing, etc., all the tools available to a filmmaker, to tell a story, to define character, to propel a movie forward, without simply pointing a camera at two people in a room and watching them talk. Which is what so many movies consist of, almost entirely, be they Oscar bait dramas or super-hero extravaganzas. Once you strip away the arty production design or the $200 million in special effects, you’re left with two people in a room telling you the story. Because it’s easy to shoot people talking, easy to listen to them tell you what they’re thinking and what the movie is about. It’s a lot harder to invest the images themselves with meaning, and to edit those images together in a way that informs character and theme and story.

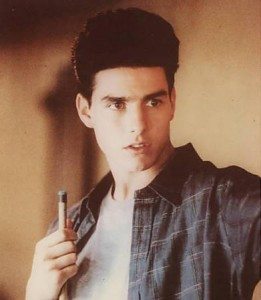

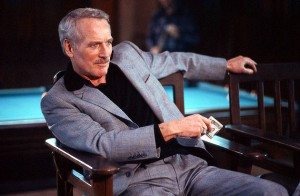

So, The Color of Money. It’s twenty-five years after the events of The Hustler. Fast Eddie Felson sells whiskey in bulk to bars, and he’s good at it, he knows how people work, so he knows how to sell. He’s a success. And then he spots Vince (Tom Cruise, expertly used by Scorsese in this role, playing to a tee a not terribly bright, hot-headed kid with a big ego), whose attitude and skill with a cue reminds him of himself. He takes Vince and his girlfriend on the road to a nine-ball tournament (it’s the ‘80s now, and nine-ball is the opposite of straight pool, fast and flashy, some games decided on the break), figuring he can use Vince’s “natural flake” to win a lot of money.

But this journey isn’t about Vince. It’s about Eddie rediscovering himself. It’s Eddie’s journey. He’s not a liquor salesman. He’s a pool player. The movie ends with him lining up a break and announcing, “I’m back!”

The opening scene lays out the entire movie in microcosm.

A close-up of a glass of whiskey and Newman’s voice, “Color, check the color,” referring not to money but to the brown of the liquor. Pan across the bar, cigarettes, twenties fanned out, and Fast Eddie pours a shot while expounding on the quality of the whiskey he’s selling. Pan up with his hand as he brings the shot to the nose of Janelle (Helen Shaver), the bar owner, asks her to smell it, and it’s obvious these two are more than friends as he tips the glass over her lips. Pan to Eddie and they’re in a two-shot, it’s just them and no one else in the world. “Very good stuff,” he says, and in the tiny pause before his next line we hear the click of pool balls somewhere in the background. She invites him to her place that night and their flirtatious talk turns to what kind of omelette he made her the last time he stayed over.

With that simple an opening, Eddie’s whole world has been established. He sells whiskey, he’s polished, he’s got money, he’s got a woman who loves him who he probably only sees whenever he’s in town. No one else is in the shot, there’s nothing else in the world but the two of them.

“Hey,” someone taps Eddie’s shoulder, he knocks the hand away, he’s talking omelettes with his girl. The hand taps him again, he knocks it away, they finish their conversation. “Excuse me,” he says to Janelle, and the camera—still the same shot—swings over to Julian (John Turturro), and now it’s just Eddie and Julian, and Eddie’s pissed off, he’s working here, but Julian is too, says he’s got a guy up to $20 a rack. “What guy?” and we cut to their POV of Vince playing the racecar videogame Stocker. The camera swings back to all three of them. Janelle looks annoyed at the interruption. Julian says he’s been playing the kid off. Eddie hands him a twenty. The camera follows the twenty into Julian’s hand, and follows Julian to the table, where he tries to get Vince away from his videogame. Vince’s girlfriend, Carmen (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), sits in the background.

Cut back to the two-shot of Eddie and Janelle over Janelle’s shoulder. He’s talking whiskey again. The distraction is gone. And yet, behind Eddie the blurry shapes of Vince and Julian play pool. Cut to the reverse over Eddie’s shoulder, and behind Janelle, reflected in the mirror over the bar, there they are again. The world of pool is very subtly creeping in to the world of whiskey.

Cut to a close-up of the stack of twenties and Julian’s hand grabbing for one. “That was quick,” says Eddie. “I slipped.” Eddie lets another twenty go, and returns to talking whiskey.

Cut to Vince breaking the balls. Cut to Eddie turning to look. “Kid’s got a sledgehammer break,” he says, watching Vince wave his cue around. And pan back to the two-shot, Eddie talking whiskey. Julian returns for another twenty, Eddie’s pissed off, “Who you working, me or him?” Cut to Vince doing some crazy-ass mimed murder of an invisible foe with his cue. He makes out with Carmen. Cut to Eddie, watching with a brief, intense look he lets drop as he turns back to Janelle, tells her to pick out a nice bottle of wine for tonight. This nutty kid has almost got him hooked now, but not quite, and then—CRACK! Another sledgehammer break and Eddie turns to look, his expression gone hard. And that’s it.

The camera follows Eddie as he walks from the bar, from Janelle, toward the pool table. She tries for a moment to get him back, asks him about some Wild Turkey labels, Scorsese does what he does best here, swings the camera back to Janelle as Eddie kind of vaguely turns, not even really looking at her, says, “Yeah, sure,” then swings away to follow Eddie to the game. That’s the last we see of Janelle in this scene.

At this point Eddie has left the world of whiskey behind. The bar, only eight feet from the pool table, might as well be in another movie all together. He’s in the world of pool now. He stands watching Vince make quick work of poor Julian. And then he notices Carmen, seated, watching the game. Eddie sits just behind Carmen in a chair that’s raised above her. Because Eddie exudes power. He is very much in charge. She ignores him.

Vince wins easily. Wants to play again. Julian says he’s done, he’s bust. Vince offers to play him just to play. Then offers to pay if he loses, but to take no money if he wins. It’s an absurd thing to say. Julian takes it as an insult and leaves without saying a word. Eddie watches it all, completely fascinated. He’s watching himself at that age, at the time of The Hustler. He’s being shown who he was, he’s being reminded of the other person inside of him, hidden for all these years.

Something else happens in this moment, not about Eddie’s inner state and eventual transformation, but purely in the sense of the story. Eddie comes to an inner decision: he sees something in this kid, and he knows how he can use that something for his own ends, i.e. money, on the surface of plot, and, in the deeper sense of theme, finding himself. How to make this work? He sees it right away: through Carmen.

Vince goes about trying to get anyone to play him, but no one dares. Carmen asks Eddie if he wants to play, “Sure.” “Twenty a rack.” “Five hundred a rack,” says Eddie, and shows her the money. She freezes up. She doesn’t know what to do. Eddie calls her on just that, says with both arms in traction Vince beats anyone in the room. He offers her the money again. She still doesn’t know what to do. He tells her she should say no, because who knows if he’s hustling her or what; he’s an unknown. “He,” pointing at Vince, “should be the unknown.” He goes on about how beautiful that would be, if one could control that. He’s getting this idea into her head without her even realizing it, the idea that real money could be made if Vince was used the right way.

He offers her the money a third time. “No,” she says immediately. He smiles. “Actually, you should have said yes.” As almost an afterthought, he offers to take them to dinner. She says he should ask Vincent. “No,” he says, “you should ask Vincent.”

That’s the scene. Eight minutes, 40 seconds for the whole movie to be laid out, both the surface mechanics of the plot, and the ultimate meaning for the man it’s all about. Every major relationship (save a later one between Vince and the bad guy Grady Seasons) is shown, we know all we need to know about the last twenty-five years of Eddie’s life, the story moves ahead, and all without a single line of expositional dialogue. We see all of this through the relationships between characters, through the way Scorsese frames the shots, how he separates the world of the bar from the world of pool, and how these moments are edited together to give it all a sense of continuous flow and forward motion. It’s a beautiful thing.

Nice, more of that

Thanks. I’ll see what I can do…

Just read this again. Really great post, this is the type of thing movie sites and magazines never do – stuff that explains the mechanics and grammar of film – they’re more concerned with being marketing funnels.

As that guy said, more of these pieces.

One actually in the works today. If it works.

Thanks. Yep, we were just talking about writing more like this.

Finally got around to watching both of these over the last two nights.

I read this post again before I watched The Color of Money, great post, it made watch the film in a different way. I was more aware of how Scorsese moves his camera and his use of zoom. There’s some great shots in it.

I really enjoyed both films but I thought that The Hustler is the better film overall, Eddie is just so much more complex a character in that and I thought Piper Laurie was given more to do than Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio.

The narrative in The Color of Money is a bit more straightforward and he’s easier to root for because some of the edge is gone from his character, and that’s just the kind of story it is but it’s done so well. Tom Cruise is so good in it. Having said that I loved the ending of The Color of Money, it’s perfect.

I think it’s interesting that people go on about the 70s being the time that Hollywood went all dark but The Hustler is 1962.

And seriously, how good looking was Paul Newman!