Movies ate my brain! They’ve eaten yours, too. They are insidious and powerful, they crawl into your head through your eyes and ears, spin their nests out of sparking ganglia and creep about inciting neurons to join together in strange new patterns, arranging them cell by cell into a wholly new you, one movie at a time. I’m not talking about movies that make you see the world in a new light, that make you think new thoughts about people or ideas, although the best movies have exactly that effect. I’m talking about the movies that achieve something still deeper and weirder, those that send you out of the theater with a brain wired differently than the one you walked in with.

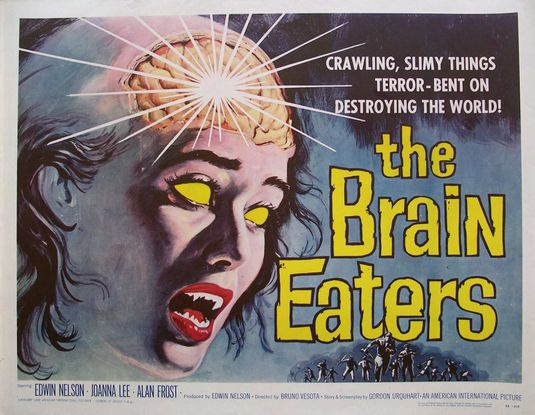

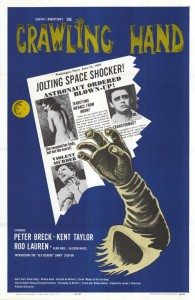

Movies got to me at a young age. Vivid memories remain from long ago. I can still see myself at nine watching the scene in The Empire Strikes Back when, ever so briefly, Darth Vader’s burned up head appears. I can still picture the Alien chest-bursting scene not as it played out in the movie, but as I imagined it when an older kid described it to me. I can still feel the terror of watching The Crawling Hand on TV on a Saturday afternoon. It was the hand of a blown-up astronaut, possessed by a space demon!

Many movies have rearranged my cranial furnishings over the course of my life. But three stand out from the rest. Three movies didn’t just rearrange the furniture, they broke in, doused the place in gasoline, torched it and rebuilt from the basement up. The thing of it is, I can’t point to anything specific these movies changed about me. I can only say I was not the same person after I’d seen them. These movies ate my brain.

An American Werewolf In London

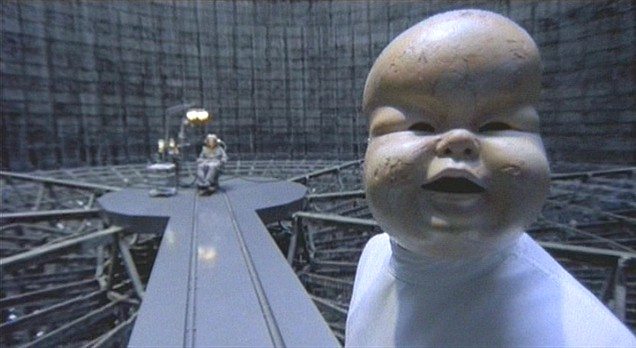

Take a look at this still from one of the dream sequences:

This is the single most frightening image I’ve ever seen. I have no idea why. It lasts for little more than a second. It’s featured in a movie that includes Nazi werewolves cutting throats, mutilated corpses eating toast, and a werewolf biting the head off a cop. Yet even now, looking at that frame, I find myself so primally disturbed that actually I’m not even looking at it. I’m going to put it in last when I’m done writing and never read this post again.

I saw Werewolf when it opened in ’81, I was ten, I said to my dad, “Dad! Werewolf movie. Let’s go!” and he said, “Werewolves? Great!” I don’t know what logic led him to take a ten year old to this violent, horrific monster movie, but it’s exactly the sort of logic I’ve used ever since (like when I was thirteen and took my grandmother to see The Terminator [she wasn’t impressed]). Unfortunately I also invited a friend who was, unlike me, a normal ten year old. Which is to say that just after the demonic Nazi attack, before our hero even turned into a werewolf, my normal friend, already having been irrevocably scarred for life, said he had to leave. I left with him. We snuck into Victory starring Sylvester Stallone, Max von Sydow and Pele. Remember that one? That’s okay, no one else does either. It features soccer playing Nazis, which aren’t nearly as frightening as the undead kind.

After the movie my dad, eyes aglow with wonder, described in detail the transformation scene, down to the stretching hands and sprouting hairs. I was devastated. How would I ever see this R-rated movie in its entirety? It was ’81. No one had VCRs yet. I was doomed!

I obsessed about this movie for a full year. I stared slack-jawed at the Life Magazine photo-spread of the transformation scene day after day. I made a new best friend who liked ghastly horrifying movies as much as I did. I took to reading Stephen King novels. And then, a year later, in the summer of ’82, Werewolf played at the glorious New Varsity Theatre on a double bill with The Howling. Lucky for us, my dad hadn’t seen The Howling. He took us to the first show, and left us alone with Werewolf.

It’s a strange movie. Not a lot happens. It’s funny in a way horror movies weren’t supposed to be back then, confusing the hell out of critics. The ending is inevitable and terribly sad and so abrupt it’s startling, with the Marcels’ doo-wop version of Blue Moon blasting over the credits. It’s horrific, bloody, hilarious, there’s a hot sex scene entirely inappropriate for ten year olds, an outrageous sequence of mayhem in Piccadilly Circus, Frank Oz appears briefly, as do the Muppets on a dream-sequence TV, and it features a still never topped werewolf transformation by the amazing Rick Baker. It was the best movie of all time. Better than Raiders, better than Star Wars, better than everything. It scared me shitless and I loved it. And it didn’t hurt that Jenny Agutter was in it.

I think Werewolf opened up a door in my brain and let the monsters in. I don’t really know what that means, but it feels right writing it that way. It’s like in Gremlins 2 when they get into the projection booth, that’s what the monsters unleashed by Werewolf did to me. They melted the film and re-spooled the projector with something entirely new and weird and I’ve been watching it ever since.

Brazil

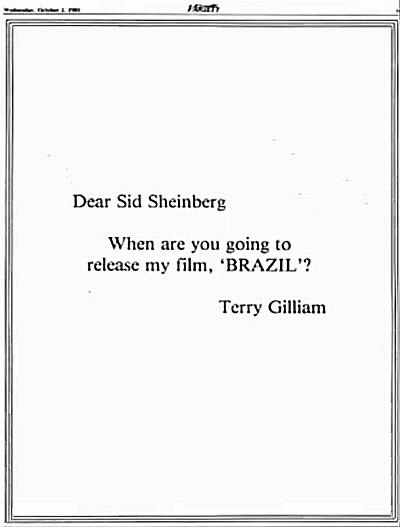

Like any self-respecting twelve year old, I was in love with all things Monty Python. When Time Bandits opened I saw it at least five times. Needless to say, its effects have lingered (name of this blog, my screen name, etc.). Then in ’85 came word of a new Terry Gilliam movie, a movie so strange that a bean-counting fuckwit producer at Universal was refusing to release it. I followed every facet of the unfolding drama, from Gilliam’s full-page ad in Variety—

–to the secret screening for the L.A. Film Critics (who promptly voted it Best Picture of the year), to the rumored studio re-edit turning it into a happy love story. Finally, months later, in Feb. ’86, it opened, in a version eleven minutes shorter than the European release, but with the edits made by Gilliam himself.

Brazil is a crazy dark movie set somewhere in the 20th century. It’s the present seen as the future filtered through the past. It’s bureaucracy overpowering imagination. It’s funny and bizarre and full of Pythonesque touches. It ends with a kind of hope so grim I’m not even sure it counts as hope. How could I not love it?

I saw it with a group of friends one afternoon at the Stanford Theatre. It re-wired my brain, replaced the whole fuse box and upped the amperage a hundredfold. Visuals crackled and popped inside my head like the whole movie was re-playing itself on the insides of my eyeballs. As friends repeated my name I’d snap out of my waking dream-state crying “Buttle!” only to fall back in. Walking down the sidewalk it happened to all of us, like the memory of the movie was a physical entity that once inside our minds wanted total control. The feeling passed, but I don’t know if it won or I did. Or if there’s a difference. I was not the same person after Brazil. I’d plugged in the monsters and lightning shot from their eyes.

Lawrence of Arabia

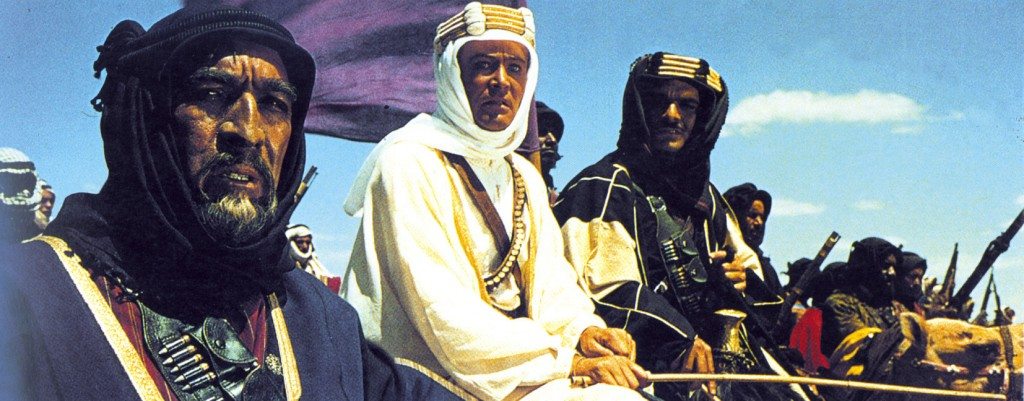

I graduated from college with a degree in anthropology and knew I had to make movies. What are movies, after all, but the study of primates? I lived in Los Angeles. I was seeing over 200 movies a year in theaters (thank you, New Beverly!) and still more on video. I made lists of famous directors and their famous movies and systematically watched them all. Under David Lean was Lawrence of Arabia and I’d come to understand that it needed to be seen on the big screen. So I waited. It was going to be an old, dull epic anyway, what was the rush? I hadn’t thrilled to The Ten Commandments, after all. Could this be any better?

Oh, ignorance! You’re so charming from a distance.

Lawrence came to The Cinerama Dome for a week-long run, a newly struck 70mm print of the recently restored (in ’89) version.

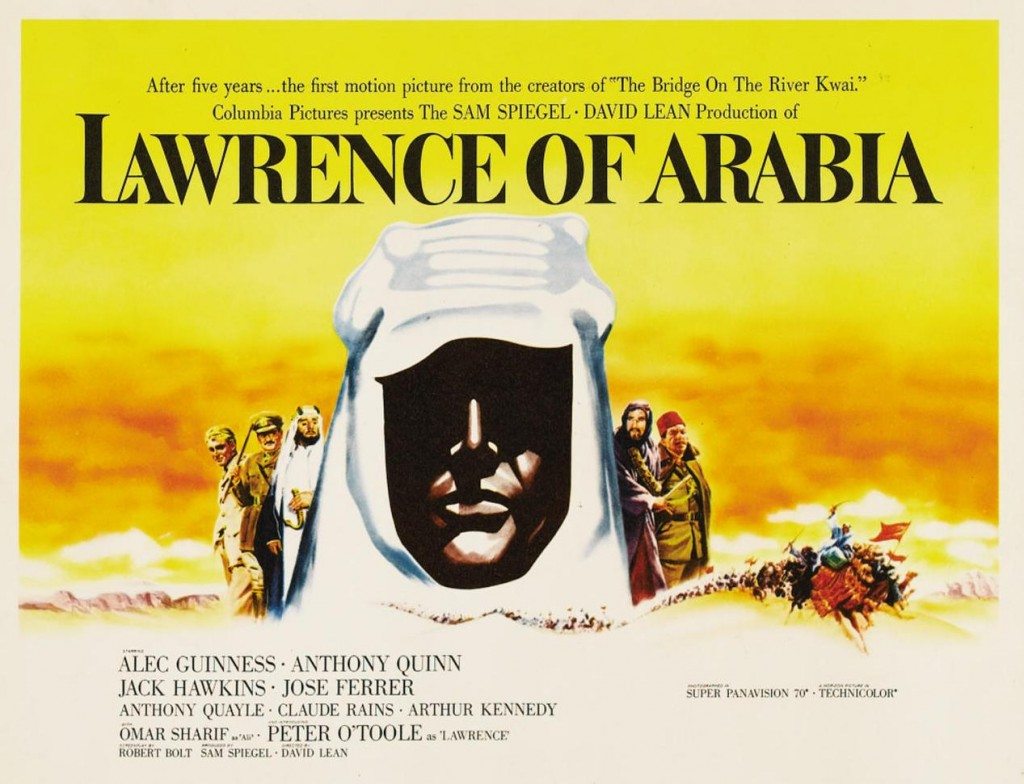

I saw it on Sunday night. I sat in the front row, gaping in awe for the full three hour and thirty-six minute running time. I could not actually believe what I was watching. The movie melted my brain with its fiery desert heat, poured it into an Aqaba-shaped mold, let it harden, and stuck it back inside my head. How had anyone made a movie like this? Why had no one made one since? The universe ceased to make sense! A movie more vast in visual scope than any I’d ever seen, yet where every scene is about one character’s interior struggle to find himself. The movie exists as one question posed over and over again: who is Lawrence? And then, in the end, it has the balls not to come up with an answer! How can that possibly work? Look at the original poster art:

Hard to imagine that Peter O’Toole’s face isn’t in the poster. Only a shadowy hidden man, invisible to himself as much as to us. But O’Toole was an unknown. He wasn’t the selling point, not yet. This was his first movie. In which he gives arguably the greatest performance of all time. There’s not a boring second in this movie. It’s shot so beautifully you could cry just thinking about it. You could cry thinking about the editing, it’s so beautiful a movie. Every line is quotable, from the most meaningful: “Colonel Lawrence, what attracts you personally to the desert?” “It’s clean.” To the most random: “He likes your lemonade.” It is in totality one of the most moving artworks in any medium I’ve ever seen. And I’ve seen some art, dammit! Any time it plays theatrically, I see it. I’ve never watched the whole thing at home. It exists for me only in a darkened theater.

And so. The electrified monsters had been given camels and ridden into the middle of the desert, that sea in which no oar is dipped, and there they would remain. Which what the hell does that mean? I don’t know. I only know that movies filled my head with monsters on camels, and that if they ever make it across the Sun’s Anvil, there’s going to be ice cream for everyone.

Many movies have seriously tinkered with my consciousness, but these three stand out. They chart a certain journey, I think. Nightmares of the monsters within at age ten, nightmares of a mechanized society crushing the imagination at age fifteen, and at age twenty-two the search for self, with no answers found. Which sounds a bit dark when I put it that way. But that’s life for you. Dark, funny, institutionally insane, there’s monsters, camels, Muppets and Nazis, you’ll cross many deserts, in the middle there’s hot sex, and in the end, whether or not you’ve been lobotomized, there awaits a dream of happiness.

When we watched American Werewolf at the New Varsity (Jesus, we were ten?), I remember being so scared in that first werewolf attack (which you had hyped up beforehand to an unbelievable extent) that had to sit with my knees covering the entire screen and my fingers in my ears, and I was still terrified. Yeah, that was awesome. I also had that Time Magazine photo spread (still do), and I looked at it all the time. I remember all those stills vividly.

And when we went to see Brazil, I remember that our plan was to go see the new funny Terry Gilliam movie, and then ride our bikes to the 7-11 to play video games. We never made it to the 7-11. I think we tried, but we just ended up on a park bench, not even talking, just trying to process. When people ask what my favorite movie is, I say Brazil, even though I don’t really believe in “best” movies, because no movie has ever affected my physically like that. I was stunned.

Glad I waited to see Lawrence in the Dome, at your insistence. Yeah, that’s a good movie.

Ah, Time Magazine. I thought it was Life. No wonder I couldn’t find that issue on the interwebs.

Pingback: Brain Changing Movies v2 | Stand By For Mind Control·

I can remember seeing Brazil on one of the big screen cinemas in London’s Leicester Sq. (Odeon I think), it wasn’t a packed house probably about half full.

When it came to the final scenes of the rescue from the torture room, the audience were cheering buoyed along with the exuberance of the moment; however when the reality was revealed that it was just his imagination saving him from the terrible situation the whole audience, myself and girlfriend of the time, were stunned to silence, the film ended the titles rolled and the house lights came up I think the whole audience still reeling in shock sat silent for several seconds only then did a low murmuring of comments start as people awkwardly composed themselves and left the theatre.

Truly an outstanding example of the power of a film that had a deep and lasting effect on my own and the minds of others.

And yes, not that I got a credit but I worked on Time Bandits doing some fill in smoke effects for bits that needed to be re-shot.

I’m not alone! Thank you for writing this. I feel the same way about the movies you mentioned. But, Blade Runner is the best movie ever made.

It’s wonderful to know that someone else grew up with a Father that allowed them to see movies that changed their lives. Python is amazing! ‘Time Bandits’ and ‘Brazil’ are life changing, as well as ‘Werewolf’ and ‘Empire Strikes Back’!

I copied your post to a Word doc, because you’re pretty damn cool! Stay open eyed and never take for granted, the beauty of cinema.

Thank you. Indeed you are not alone. I will keep my eyes open. There must be a movie around here somewhere…