Last week, the Supreme Being was kind enough to share some thoughts on the films which remapped his neurons. Since we heard his confession, I’ve been trying to ensnare the cinematic wonders that did the same for me.

Upon consideration, here are a few films that I blame specifically for turning me into a film junkie.

Jaws

As far as I know, the first film I ever saw was Jaws. I was five.

My parents took us to the drive-in in Woburn, Massachusetts. Sitters were more expensive than tickets to the drive-in, so we all went. My folks aren’t crazy people, though; they went to see Annie Hall, not Jaws. This was 1977. Annie Hall had just been released and Jaws was back in theaters for another run.

Anyway, as you might imagine, being five years old, I didn’t much care for Annie Hall. I felt its over-intellectualization of romance kept the characters at a remove, so I crawled into the way-back to play. Through the big window at the butt-end of the family station wagon, I ended up watching the film on the other screen.

On the glowing wall before me, I watched the Orca chum the Atlantic—the same sea we vacationed on come summer. As Alvy Singer wooed Annie Hall through the window-mounted speaker, a monster of the depths prowled, hungry and insatiable. That may be the most astute piece of inadvertent film commentary in the universe. (There are many, actually, who will claim the novel—and by association the film—Jaws is about infidelity.)

I do not think I’m exaggerating when I say Jaws scared the pants off me. I had trouble getting in any body of water larger than a sink until I was a teenager. Even after, sharks remained my number one fear. I avoided horror movies. They were scary to me, real.

Now I can’t say how much of Jaws I truly absorbed in 1977. I do know that when I finally watched the film again, I felt as if I was as brave as Chief Brody. There was actual terror for me to conquer. Just by sitting through the film—and enjoying it—I was somehow heroic.

My fear of Diane Keaton, however, has never waned. Such is the power of the Ludovico Transformer Treatment and the Kuleshov effect. There are, indeed, strange pathways through the universe which only our brains may travel.

Whether I was cognizant of it at the time or not, I learned my first lesson in how cinema alters our perceptions of the world while I was watching a giant shark learn to smile.

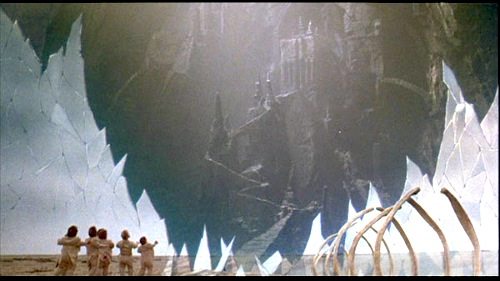

Time Bandits

Terry Gilliam has done more for this world than the United Nations and the Earl of Sandwich combined. Brazil, a film the Supreme Being included in his list of brain changing movies, is one of the finest pictures ever made. I did not see Brazil when it came out, however, and so it did not have a chance to change my young brain. Unlike the Supreme Being, I grew up in a rural area. There were no movie theaters I could get to on my bike. If I wanted to see a film (and I did), I had to beg my mom to drive me.

Time Bandits, though, was a special case. I was older by the time Time Bandits came out—nine to be exact, in November 1981. I would like to say that I begged my mother to take me to see it; that I was even aware it existed. I’m not sure I was. This was before I had devoted my free time to film. Time Bandits was my first true turn towards the light.

All I know is this: One evening, crisp and cold, my father told my mother he was taking me to the movies. If he mentioned what the film was, I don’t recall—as I said, I doubt the title would have meant anything to me then.

Dad bringing me to a movie wasn’t too unusual, either. I distinctly recall him taking me along at least once before, to see Capricorn One. What made this evening stand out was that my parents fought about it. My father wanted to take me to a late show. My mother said I was too young.

Now, my parents didn’t really fight much, or ever. But I remember my mother putting her foot down, insisting it was too late for a little pisher like me. And I remember my father saying something along the lines of, “We’re going to the movies. I’m taking the boy and that’s it!” He defied my mother and did so in my favor.

Something important was clearly happening.

And boy, was it. Time Bandits is, I sincerely believe, the best kids film ever made. It is imagination made real. It is a glimpse of the wriggly chaotic world in all of its horribly flawed magnificence. Heroes are indifferent and immoral. Villains are clever and look ever-so-much like the people you admire on the tube. The people your teachers make you memorize facts about? What are their grand aspirations? To watch little people hitting each other.

If you happened to be a solitary kid like I was, prone to sticking your nose in a book, then watching Time Bandits was the Acid Test. As far as I’m concerned, it still is. If you don’t get or don’t like Time Bandits, I’m happy to hear what you have to say, but I’m not sure I can take you seriously. You might not know, you see, that the Supreme Being is just a bureaucrat doing a rush job. That minds can be controlled, easily, by evil.

Time Bandits tells kids the one thing they most need to know: there is no grand truth to the world. The place isn’t even properly finished yet. If you want to get by, better start managing things for yourself. Good luck. Here’s a map.

This site is named after a line from the film because Time Bandits trusted me with secrets. Men, even the lords of history, are flawed. God can’t be trusted. The most fabulous object in the world is nothing but a trap. It’s evil. Don’t touch it.

Back to the Future

Four years later, in the summer 1985, my family drove across America. We took the southern route from Massachusetts to Los Angeles, then came back across the northern states. By the time we hit Wyoming, I was voluntarily riding in the back with the dog. That was better than cramming in with my sister and brother in the middle. My dad played weird new age music and I read some book I had bought second-hand from a gas station. It was about an astronaut who was captured by lobster-men and caged in a zoo on their home planet.

In Wyoming, we went to the rodeo and then hit the drive-in. The feature was Back to the Future.

Back to the Future may not compare to Time Bandits on many levels, but still: I love it. It’s an adventure story of the right temperament for a budding young sci-fi dork, trapped in the car with his siblings, stupefyingly bored of looking out the window.

But I cannot honestly say that I adore Back to the Future for it’s merits alone. This film makes the list because of circumstance. As we watched the story play out on the giant drive-in screen, the darkness of the plains flickered. We were set on the edge of a featureless expanse that drifted off into the black distance. Somewhere, beyond the screen, lightning danced—orange, blue, purple.

What we had here was a good old American lightning storm.

As Marty McFly and Doc Brown tried to scrounge up 1.21 gigawatts, the storm slowly crept our way. You could feel it in the air as brittle edge. Time was running out.

Can you picture it? Marty floors the Delorean, burning down the street, sparks crackling. Atop the clock tower, Doc fights to make the only connection that could possibly throw McFly forward through the years. The timing is crucial, but the storm is not helping. A branch falls across the wires, breaking the circuit. Beyond the screen, lighting flares as well, feeling closer, but all perspective is gone.

And just as Doc Brown grabs the loose connection ends and slams them home, just as Marty McFly snags the cable with his hot rod time machine, just as the lightning strikes the clock tower—I shit you not—a bolt of clear white electricity flings down from the heavens and slams into the projection booth.

I really don’t know what else I can say about that. The film went out, as did all of the power. People emerged from their cars and looked about at each other with befuddlement. It was as if, because of some strange flaw in reality, we had stepped inside the film.

Eventually, they got the film going again and we all watched the end. But it didn’t matter. We had seen the best part.

We had learned that a movie—a special one—isn’t a story told to you; it involves you, and, doing so, becomes real.

I was going to provide a link to the shark line in Annie Hall, but I see you got it in there. Good work.