Americans love criminals. Something to do with the old west, or anyway the idea of the old west, of gunslingers roaming free across endless stretches of unexplored country, killing to stay alive, free from law, from government, from society itself, answerable to no one but themselves, free to act as they please, no matter the consequences, every man for himself and screw the other guy, all of this bundled up into that most beloved of American concepts: individualism.

Americans love their individualism, they shine it up, put it on a pedastal, cut off its arms and head and call it art. Only how can you express your individualism with all of these other jerks expressing theirs? Them and their laws and taxes and social mores and whatnot, always knocking over your pretty headless statues. What a pain in the individual’s ass! What we all want to do is steal a Cadillac, rob a bank, and hit the road with the innocent gal/fella of our choice, shoot anyone who gets in our way, and if we end up dead, well so what? Live free or die, motherfucker! As I believe the expression ran before those damned bluenoses got to it.

Of course we’re not actually going to go out and do any of that. Instead, to sate these deepest of yearnings, for most of us unfulfilled, we will wallow in the sub-genre of the crime film known as Lovers On The Lam, where a couple of foolish, young, law-breakin’, good times havin’, murderin’ lovers commit a string of crimes with the law on their heels, in exactly the way we wish we could. Or so I surmise.

Six of the most well known Lovers On The Lam movies are:

Gun Crazy (’50)

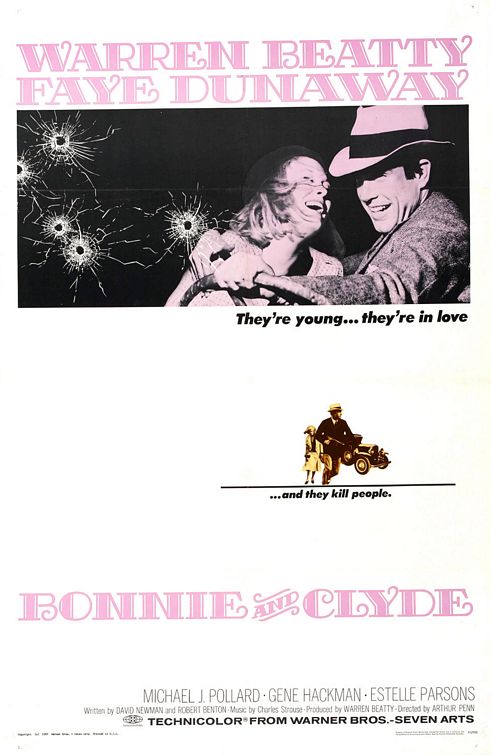

Bonnie And Clyde (’67)

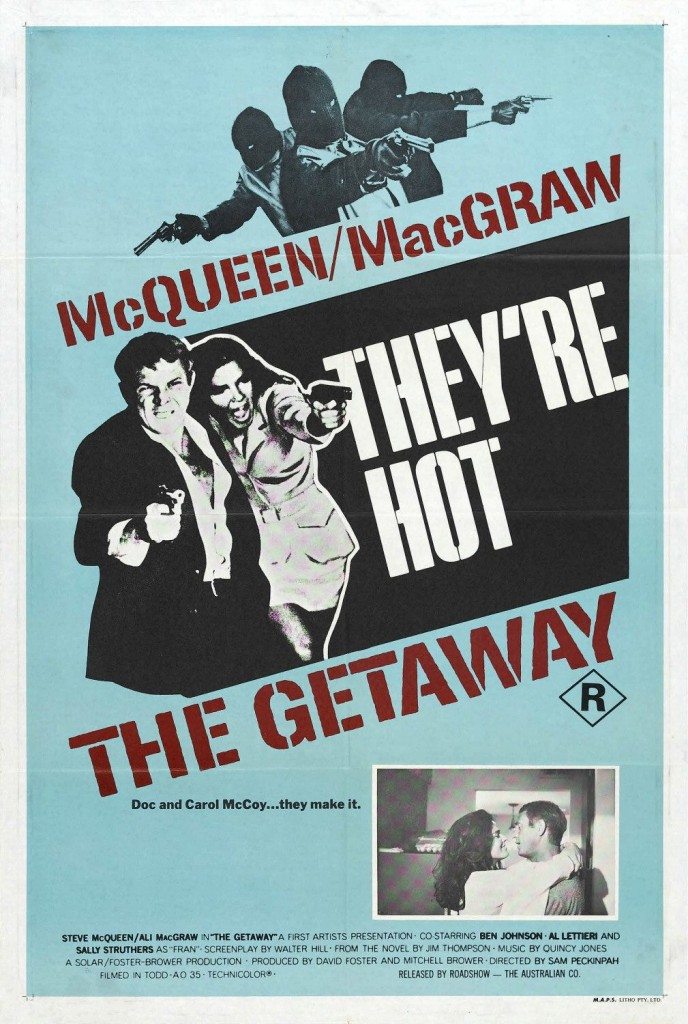

The Getaway (’72)

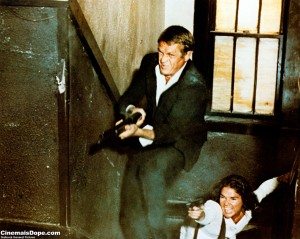

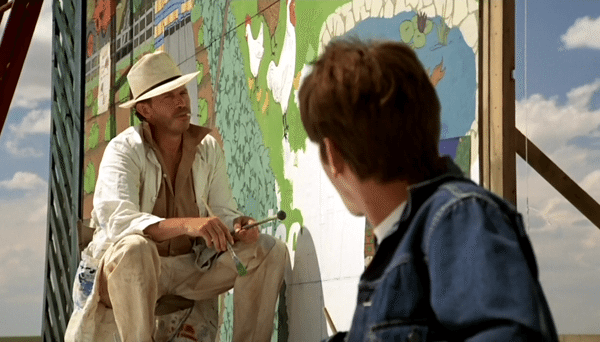

Badlands (’73)

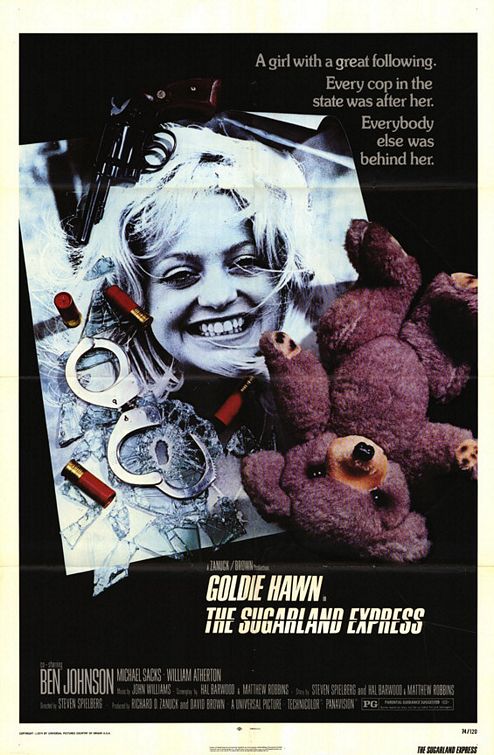

The Sugarland Express (’74)

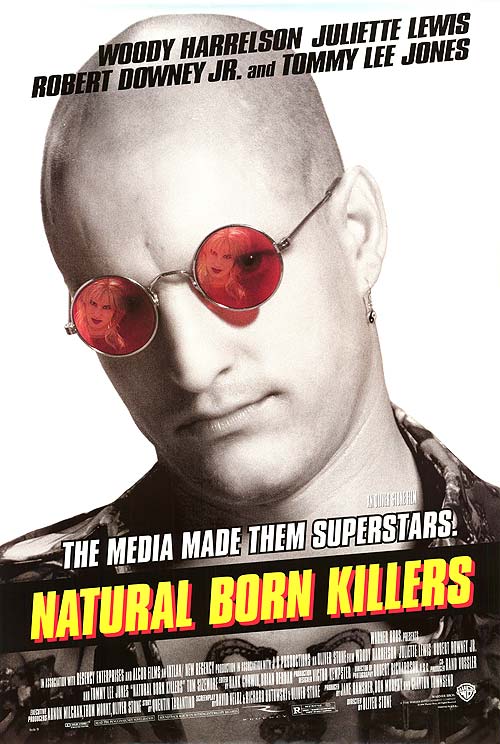

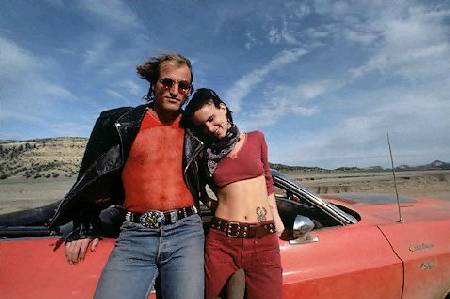

Natural Born Killers (’94)

The concentration from ’67 to ’74 is telling. Bonnie And Clyde is considered the kicking off point by many for a decade plus of movies focusing on anti-heroes and other outcasts, movies with simple stories and little in the way of plot, movies centering almost wholly on character and mood. So not only did young filmmakers looking to make a name for themselves want in on aping Bonnie And Clyde (Spielberg), so too did older, established ones (Peckinpah). Movies went through a serious slump in the ‘60s. Bonnie And Clyde freed them.

How did it do this? With inspiration from Gun Crazy, which may actually be the best of the lot. Gun Crazy drew the map for these kinds of movies, despite differing in major ways. First of all, unlike every other movie on this list, in Gun Crazy it’s the woman, Annie Starr, played with a wonderfully amoral glee by Peggy Cummins, who starts all the trouble, who lures her lover into a life of crime.

It all begins with young Bart breaking into a store and stealing a gun. Not because he wants to shoot anyone. He just really likes guns, and wants one handy at all times. Even in his grade school classroom. In fact, as all his friends attest, he wouldn’t hurt a fly, he wouldn’t even shoot a mountain lion for a bounty. A mean old judge sends him to reform school anyway. He returns to town an adult, after a stint in the army as a marksman, and happens upon a circus where Annie wows the crowd with her shooting act. Bart falls for her and joins the circus, but it’s not long before the jealous circus owner gets rid of them both.

First things first back in ’50, no matter the protagonists’ lack of morals, they get married. Because how else could they screw? Rules is rules, people. Bart’s in love. He wants to get a regular job. Annie’s in love too, but she wants the good things in life, so it’s robberies or nothing. He goes along grudgingly, the poor guy, though he has plenty of fun on jobs.

One bank robbery is filmed from the backseat of a car all in one take as Bart and Annie arrive at the bank, deal with a nosy cop, rob the place and tear on out. Which long take in an actual car, with no rear-screen projection, is mighty unusual for a movie from ’50. It looks great.

Eventually they decide on the classic “one last job,” a payroll robbery. It goes fine until Annie shoots a woman out of spite and a cop because he’s there. They’re chased into the mountains, into a misty swamp, and come on now, this is the ‘50s, it’s no surprise they both die. They have to. I won’t say how it goes down, but I will say it’s morally perfect, and profoundly twisted, all at once.

Now when Bonnie And Clyde came along, the rules of who’s good and who’s bad had yet to fall to pieces, and if you don’t know how it ends, well, sorry, but you’re about to find out. Our heroes are machine-gunned down in an orgy of bullets and blood and slow motion no one at all was prepared to see in ’67. This sort of thing simply wasn’t done. Sure, they had it coming, but this wasn’t the moralistic ‘40s. Bad as Bonnie and Clyde were, they were the heroes. In other words, the ending managed to be subversive by applying the rules of gangster films of old to modern characters. It was also one of the first movies to show bullet hits with blood bursting out of them. In the past, movie shootings were bloodless.

Sex is handled strangely in the move. Originally Clyde was supposed to be bisexual. He and Bonnie and their getaway driver were to all get it on together. Stories conflict as to why this was dropped. Arthur Penn, the director, went the opposite direction and made Clyde impotent, which really freaks out Bonnie at first. She gets over it, falls in love with him, but throughout the movie there’s an underlying tension at Clyde’s inability or unwillingness to have sex with her. He does eventually, once Bonnie’s poem about their exploits is published in the newspaper. She finally made him famous, he says, before jumping her.

The movie is full of strange tonal shifts, with robberies played close to farce followed by bloody, intense shootouts, and the kind of jarring editing becoming popular at the time, for which we can blame the French, particularly Godard and Truffaut, and their hip new-wave shenanigans.

But getting back to our lovers on the lam, Bonnie and Clyde make a great couple. They’re both screwed up, we can see that even if we don’t hear about their childhoods, and their love for one another is palpable, just as it was in Gun Crazy, despite the lack of sex. They’re fun to be with, just like Bart and Annie.

At the other end of the “fun to be with” spectrum we have The Getaway, Sam Peckinpah’s movie version of the Jim Thompson book, in which the lovers, Doc and Carol, played by Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw, are so inert, unlikeable and uninterested in each other you worry one or the other is going to collapse of boredom midway through. Which is odd, since MacGraw and McQueen had an affair (she was married to producer Robert Evans) during the production. I hope their real life love was more exciting than this movie.

I wish I could describe the plot, but none of it makes much sense. Doc is in jail and wants out, so he tells Carol to tell the warden he’s for sale. It’s unclear what Doc imagines Carol’s going to do, but what she does is fuck the warden so he’ll parole Doc. Which he does. Then he hires Doc to rob a bank with a couple of thugs, including Virgil Sollozo from The Godfather (okay, actor Al Lettieri, but he’ll always be Sollozo to me).

It all goes to hell, leaving Doc and Carol on the run with all the money from the botched robbery, and Sollozo, left for dead, on their trail in a totally bizarre subplot wherein he abducts a veterinarian and his assistant, Sally Struthers, who plays some kind of sex-starved veterinary minx in love with bad men wielding guns. They even lift the famous moment in Bonnie And Clyde where Bonnie strokes the barrel of Clyde’s gun, with Struthers practically giving a hand-job to Moe’s piece.

Inexplicably, Doc and Carol, on the run, head to the one hotel in all of the U.S. where every other character in the movie knows they’d planned to go. Everyone shows up, and Peckinpah gives us his patented slow-mo, fast-edited, blood-soaked shoot-out. Doc and Carol make it out alive and escape to Mexico with the help of Slim Pickens, and ride off into the sunset.

Is there a theme to this movie? A meaning? Beats me. Bad people who kill people are good if the other bad people are worse? So they get to live? Bonnie And Clyde tells us that you can’t live free, that the powers that be will conspire to take you out. The Getaway tells us nothing about anything.

Terrence Malick, the writer and director of Badlands, his first movie, goes back to the theme of Bonnie And Clyde: you can’t be free. Martin Sheen plays Kit, a kind of greaser kid (it’s set in the ‘50s) who takes a liking to Sissy Spacek’s teenage Holly. They start dating and sleeping together, but her dad, a mean Warren Oates, forbids them to be together. Kit shows up at their house one day and in a low-key, oddly unaffected scene, shoots Oates dead. Holly reacts with little emotion. They burn down the house and the body in it, and off they go, on the lam.

Malick has said he wanted these characters to feel as if they were in a fairy tale, and he pulls it off. Bad things happen in fairy tales, and they never cause overwrought emotional outbursts. Likewise, there’s little emotion in Badlands. Things just happen.

Following their escape, there’s a long, dreamy sequence of Kit and Holly making a treehouse in the woods and living free and happy, told in montage with Holly narrating in voiceover, a sequence very similar to those in Malick’s more recent films like The Thin Red Line and The New World.

Bounty hunters snoop them out, Kit kills everyone in his way, and they’re off. At this point they don’t seem much like a couple, let alone young lovers. Kit is a cold-blooded killer, and Holly’s just along for the ride, telling us in her voiceover that she’s considering running away, yet never doing so. Until one day when a helicopter swoops down on them and she does.

Before that they spend a fair amount of time driving through the desert, going nowhere, doing nothing. It’s a peculiar vibe this movie has, hazy and lost and burnt by an ever-orange sun, but it’s always compelling. You want to know what happens next.

Ultimately Kit gives himself up in a car chase. He has the cops beat, but decides it’s time to get caught. He and Holly have become minor celebrities for their exploits, same as Bonnie and Clyde, and the cops are no more immune to fame than anyone else. Once Kit’s in handcuffs he’s harmless and charming. He becomes likeable again. Holly narrates that Kit gets the electric chair, but we don’t see it. We see them flying off in a police airplane into the clouds.

Badlands is an odd movie, with a dreamy quality very unlike the others under discussion, a quality unique to Malick. It’s not as good a movie as Gun Crazy or Bonnie And Clyde, and it’s not as good as Malick’s subsequent films (aside from Tree of Life, which I could have done without), yet it’s still well worth watching. It takes the Lovers On The Lam movie in a different direction and infuses it with a unique atmosphere.

The same can’t be said for Steven Spielberg’s first theatrical feature (his first movie, Duel, was made for TV), The Sugarland Express. Spielberg takes all the familiar tropes and manufactures something fake and unfeeling out of them. It’s a total dud of a movie.

The couple this time are Clovis and Lou Jean Poplin, played by William Atherton (who still had a dick back in these days) and Goldie Hawn. Clovis is in a low-security prison serving only four more months, but his nut of a wife breaks him out anyway. She spent time in prison herself, during which their young child was taken away and put with a nice, respectable foster couple. She wants the kid back, so off they run.

Owing purely to panic, Lou Jean screws them even further, and soon our couple has hijacked a patrol car and the patrolman inside it. They hold a gun on him while he drives. The rest of the movie is a chase, often at slow speed, with miles of police cars tailing our heroes as they make their way to Sugarland, which is maybe a city or a town or wherever their kid is.

As in Gun Crazy, Bonnie And Clyde and Badlands, we see how the world outside is following our heroes and rooting for them, despite their outlaw ways. Only in Sugarland it’s all completely boring and unbelieveable. There is zero chemistry between Hawn and Atherton. They barely even look at one another. They might as well be in different movies. Why would he go off with this crazy wife of his? The way he acts around her, it’s impossible to tell. Does he love her? Like her? Think she’s a loon? Who knows? And how does she feel about him? She never shows a thing. All she wants is her kid.

Our couple makes a deal with the cops to get their kid back, but the cops plot to shoot them instead. This they do. Clovis takes one in the belly, they drive off, he drops dead. The hijacked cop is sad, because he came to like these two darn crazy kids, by gosh, despite the whole being abducted thing. And a final crawl informs us that after Lou Jean spent a few months in jail, she got her kid back. Because she’s such a great mom? Yikes.

The one good thing to be said about The Sugarland Express is that watching it you think, say, whoever’s directing this thing has a real eye for composition; this kid might really go places if he had a script not written by lemurs high on caffeine, maybe something about, say, a killer shark?

Let’s end this discussion with one of the most wretched turds ever smeared across the theaters of the world: Natural Born Killers. Holy god is this movie awful. I saw it when it came out and hated it then, only back in ’94 it had some kind of cache, didn’t it? It was too violent to be believed! It was a statement against our TV obsessed society! It was a movie to be talked about!

Well. Bad as it was then, it’s aged like milk. It’s based on a screenplay, heavily re-written, by Quentin Tarantino, who I’m no big fan of, but my god, whatever he wrote must have been a thousand times better than what Oliver Stone came up with. Then there’s the editing, a nonstop barrage of different film stocks, crazy angles, nearly sublimal flashes of blood-covered faces and screaming devils, none of which look anything but cheap and ugly. Stone has a knack for making exploitation look bland. He’s even quoted as saying his technique for the movie was inspired by the final scene of Bonnie And Clyde, with it’s harsh cutting, moments of slo-mo, and overall shocking nature. Because as Stone must have thought, if a powerful technique stuns you in a single, meaningful scene, it will only be more powerful used for every single moment of an entire movie. Sigh.

The story follows Mickey and Mallory Knox, played by Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis, two kids with rotten childhoods who run off together and shoot everyone they come across. Mallory’s childhood is filmed as a bad sitcom, complete with laughtrack. This sequence fails so spectacularly you want to claw your own eyes out watching it. There’s nothing funny, meaningful or insightful about it at all. What’s the point? Are we to find America itself in this sitcom? Did we, all Americans, in the form of Rodney Dangerfield, rape our own daughter? Fuck if I know.

At least we get the impression these two wacky, gun totin’ kids like each other, unlike in Sugarland or The Getaway. So there’s that. They’re not believeable as human beings in the actual world we all inhabit, but you can’t ask for everything.

Anyhow, they run into an old, wise Indian in a tepee in the desert (it’s an Oliver Stone movie, remember, so it’s as subtle as being beaten to death with a hammer), whom they shoot because Mickey has a sad dream about his mean daddy.

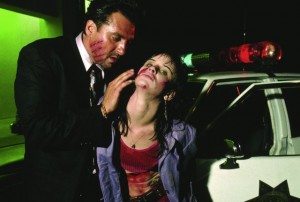

A couple of rattlesnake bites later, and our heroes are nabbed by Scagnetti, the most evil cop in the history of movies (then again, The Bad Lieutenant‘s Harvey Keitel would eat this guy for lunch), played by Tom Sizemore as though told by Stone to imagine that in every scene he’s biting the head off a live chicken. Tommy Lee Jones shows up as the warden. He and Scagnetti wear ties from the ‘70s and plot to have the Knoxes murdered in the desert.

Meanwhile, Robert Downey Jr. plays Wayne Gale, host of an America’s Most Wanted-type TV show. He talks with an outrageous Australian accent because…um, yeah, I don’t know, you tell me. He gets Mickey to sit down for a prison interview, in which Mickey spouts a lot of boilerplate psycho-talk about killing being an act of purity and so forth. Which incites a prison riot that lasts long enough for one to go to the kitchen and bake some nice cookies or maybe read a book.

Doing so you might be lucky enough to miss the scene where Scagnetti tries to rape Mallory and gets stabbed in the neck and shot in the head. Which come on, he totally had that coming! Lots and lots of deaths later, Mickey and Mallory haul their captive Gale (and his ever-running TV camera, broadcasting live, because this movie is all about the corruption of the media, people, don’t ever forget that) into the woods. Gale by this time has turned murdering accomplice, or so he thinks. The Knoxes explain that he’s mistaken; they’re going to have to shoot him on live TV. Which they do. And then run away free and happy. Cut to a future scene in an RV with their adorable kids.

Stone says the ending is meant to be happy and hopeful. Because, you see, the bad TV man gets killed, and the heroes get away and live happily ever after. Yay! This makes complete sense because even though they’ve killed like 100 people in cold blood, they, um, well, they had these bad childhoods, so, or, no, wait, it’s because they’re in love that, I mean, the point is—oh, fuck it. They’ve got guns! They’re sexy! They kill people! Woo-hoo! Only no, ooh, I’m bad for liking them, there’s all the shots in the movie of dumb citizens on TV saying how much they love the Knoxes, and that’s supposed to be us. Oh my, I see, we’re bad people for liking them, and for watching TV shows and movies that glorify them. And also, hooray, they get away in the end! It’s a hopeful, joyful movie! Thanks, Oliver!

Leave it to Oliver Stone to kill a perfectly good genre of film. Well, I’m being too harsh. You can’t kill the Lovers On The Lam trope. They’re all over the place, in one form or another. They’ll keep coming back and we’ll never stop loving them. We’re Americans, goddammit.

Gun Crazy sounds good. I’ll have to put that on the list.

Bonnie & Clyde is brilliant. I love that movie. Whatsername, the sister in law, is the most wonderfully irritating character ever.

Have you watched God Bless America? New Bobcat Goldthwait film? Haven’t seen it, but it sounds like it’s trying to fit the bill. Only fair reviews though. His last one, World’s Greatest Dad, was worth watching. Not a great movie but a bold story to tell.

I, too, was intrigued with “Gun Crazy” and purchased it on iTunes.

Unfortunately, I did not notice that it was not “Gun Crazy.” It was “Guncrazy.” With Drew Barrymore. From 1992.

And I can only assume it is even worse than even the horrific cinematic atrocity I imagine it to be.

So, buyer beware.