Nuclear devastation was big in the ‘80s. What with that son of a bitch Reagan in the White House daily taunting the Soviets, everyone pretty much assumed we’d be vaporized before the decade was out. It all started with the TV movie The Day After in ’83, directed by—hey, look at that!—Nicolas Meyer, who you will certainly remember for such gems as Time After Time and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, which was not all about nukes peppering Kansas. The Day After was about that. Khan was about Ricardo Montalban kicking ass. And Spock being awesome. Hey, quit sidetracking me.

So anyway, The Day After, very serious business at the time, we were told. Supposed to be the most realest scary-time movie ever. And maybe it was. No one’s watched it since, so it’s impossible to say. Even Reagan was scared by it, the poor old fella.

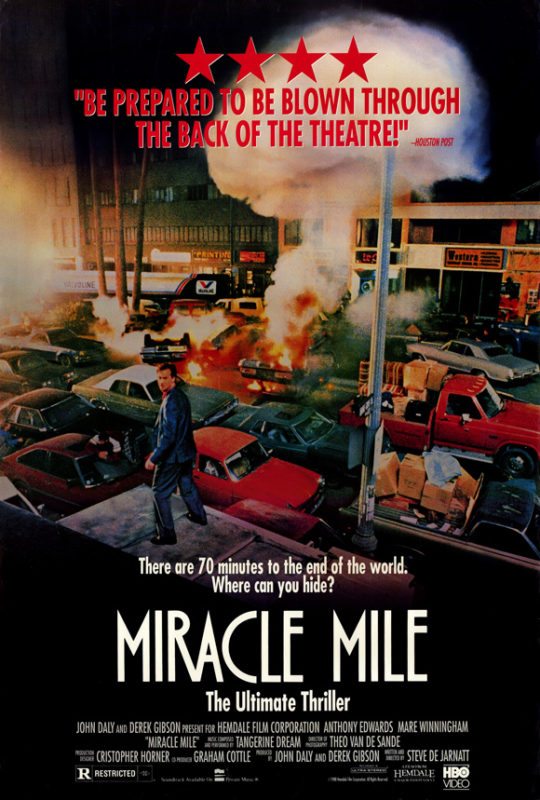

But forget that movie. I’m here to remind you of another nuclear holocaust movie that quietly turned up five years later, Miracle Mile, from ’88, written and directed by Steve De Jarnatt, who’d actually written it ten years earlier for Warner Bros. They didn’t want a first-time director in charge, and it went nowhere until De Jarnatt optioned the script himself and made the movie for a modest budget.

And it’s great. Great and totally forgotten. Maybe no one wants to remember being terrified of death by mushroom cloud? The movie starts out as this happy, dreamy love story, and then, late at night, Harry, played by Anthony Edwards, picks up a ringing phone outside a diner. The guy on the other end is freaking out. Says he’s in a silo in North Dakota, says the bombs are flying, says we’ve all got 70 minutes till they hit, and then gunfire cuts him off. An ominous voice comes on the phone and tells Harry to forget he got this call and to go back to sleep.

Harry’s convinced. He convinces the late-night diner denizens too. They flip out. And off they go to convince everyone else in the city.

Are the nukes really coming? Or was the guy on that phone crazy? Either way, as dawn approaches, Los Angeles comes alive with panic, as Harry rushes to find Julie, in theory to save her. But how do you save someone, let alone yourself, if the nukes are arriving in the hour? Would you even try? Harry has confidence in people, he has faith in kindness, but when Julie asks him if he thinks people will help each other in the aftermath, he says, “I think it’s the insects’ turn.”

It’s not a perfect movie by any means. It’s made on the cheap. There are a couple of characters that are rather baffling, like this creepy rich businesswoman with one of those late ‘80s portable phones the size of a toaster who seems to know what’s going on and requisitions a helicopter to save everyone in the diner. Other characters kind of come and go without meaning much to the story.

Yet it doesn’t seem to matter. You’re still pulled along by this rising sense of impending doom, and the central couple’s love for one another. You still feel the passion for the material the director feels. Warner Bros. offered him $400,000 to buy back the option and he turned them down. He had to make his movie, and it shows.

The whole movie is shot around the Miracle Mile in Los Angeles, a central area of the city that includes the La Brea tar pits, where the movie begins and ends.

There’s a shot at the end out the window of a helicopter of a woolly mammoth and a palm tree on fire that’s hard to get out of your head. It’s evocative in a way giant Hollywood productions dependent on expensive special effects are incapable of duplicating. It’s the simplicity of Miracle Mile that brings it to life. If you’ve never seen it, never even heard of it, it’s worth a rental.