Not so crazy about digital projection? Feeling put out by post-converted 3D crap? Having trouble watching action films without falling into some sort of strobe-induced seizure?

Not so crazy about digital projection? Feeling put out by post-converted 3D crap? Having trouble watching action films without falling into some sort of strobe-induced seizure?

What you need is some good, old fashioned peace and quiet. And by that I mean a silent movie.

Before synchronous sound changed cinema, filmmakers told entire stories without the spoken word. Without explosions or gunfire. Without laughter. You may think that that would be a handicap, but you’d be wrong. Doing without requires imagination and intensity; and that’s where the truly creative find inspiration.

If you’ve never seen a silent film (or if you’ve only seen The Artist), you’re missing out. No matter the genre, your great grandpappy and his kin struck first and struck true. In this case, we’re going to look at what may be the first True Crime film and the first courtroom drama. We’re lucky enough—blessed even—to be able to watch:

The Passion of Joan of Arc

(La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc)

Holy Jebus Crisco. If Carl Theodore Dreyer‘s 1928 masterpiece—and that’s exactly what it is—doesn’t fill you with adoration and anguish then I don’t know what will.

Marie Falconetti

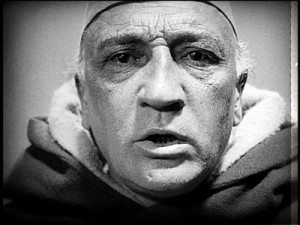

Each shot of this film is bursting with intense emotion. Despite constructing the most expensive and massive set ever made for The Passion of Joan of Arc, Dreyer shot practically the whole film in close ups. You don’t see much of the set. Instead, the screen is filled with faces—and what faces!

Without hearing a word a single character says, each personality is completely knowable through expression. And we’re not talking overdone, melodramatic stuff, either. Take a look at lead actress, Maria Falconetti. Just look at her.

This is Joan. A young woman of 19, she was commanded by god to lead the French army to crucial victories against the English during the 100 Years War. She was captured and put on trial by her enemies. This all really happened in the 15th century (assuming you believe the “commanded by god bit”).

I do not think I am spoiling anything by telling you that Joan’s story did not have a happy ending.

Was Joan crazy? A heretic as the English claimed? A saint as the Catholic Church decreed quite a bit too late to help? Watch Dreyer’s film and see: it’s based on the transcripts of her trial. Many days of inquisition are condensed into one, but the essence is in this picture. This is what it was like to be on trial for heresy in the 1400s. Not, as it turns out, a whole lot of fun.

Falconetti is only one of dozens of powerful faces that entrance you in The Passion of Joan of Arc. These close ups overflow with raw emotion and lyrical beauty. Every shot, I swear, looks like a luscious tin-type photograph; each freckle practically explodes and eyes plead and condemn so brightly it’s mesmerizing.

Falconetti is only one of dozens of powerful faces that entrance you in The Passion of Joan of Arc. These close ups overflow with raw emotion and lyrical beauty. Every shot, I swear, looks like a luscious tin-type photograph; each freckle practically explodes and eyes plead and condemn so brightly it’s mesmerizing.

Even knowing how Joan’s story ends ruins none of the pathos Dreyer brings to the screen here. We watch, along with Joan, while her morally repulsive captors taunt her, insult her faith, and refuse her even the smallest kindnesses.

Joan of Arc, as portrayed by Falconetti, is nothing if not human. She is bewildered and despondent and—insane or not—truly believes she serves the will of god. The same god that she is being punished for blaspheming.

As miraculous as this movie is, what’s almost more incredible is that we are able to see it at all. Dreyer made this film in 1928. He was not French, nor Catholic, and this infuriated nationalists who considered Joan of Arc an icon. His film was barely screened before the censors had a vicious go at it, whitewashing the portrayal of the church. Then, later the same year, fire destroyed almost all the existing copies of the film plus the negative. It became near impossible to find or see.

Undaunted, Dreyer went back and recreated the film using takes that hadn’t been in the original release. Imagine the devotion required! We’re not talking about burning another DVD—he had to dig through all the unused footage and recut his masterpiece from leftovers and scraps. But he did. And that, too, was destroyed by fire!

For most of the century, anyone who wanted to see The Passion of Joan of Arc had to hunt down an increasingly rare print of this second, alternate version; with no negative, no new prints could be made. Other versions emerged, one with tacky narration instead of title cards. It was akin to the colorized versions of classic films that Ted Turner failed to interest us in during the 1980s.

But then there was a miracle. In 1981, in a janitor’s closet, in a mental institution in Oslo Norway, some film canisters were found. When they were investigated, they turned out to contain not only a print of Dreyer’s original cut, but a print made before the church and government censors had a chance to make their changes!

That means, near 60 years after it was first made, people finally had a chance to watch the film as the director intended. And by people, I mean you.

And you don’t even have to listen to your mouth-breathing, nose-whistling husband while it’s playing! It’s silent, but it’s not silent silent.

While films from this era do not have original soundtracks or scores, music has frequently been paired with silent films to create a fuller experience. Often a soloist or orchestra would play along to a piece live, for example. In the case of The Passion of Joan of Arc, the Criterion DVD includes an oratorio soundtrack specifically written to accompany the film. This piece of choral music, “Voices of Light” by Richard Einhorn, is highly recommended.

While films from this era do not have original soundtracks or scores, music has frequently been paired with silent films to create a fuller experience. Often a soloist or orchestra would play along to a piece live, for example. In the case of The Passion of Joan of Arc, the Criterion DVD includes an oratorio soundtrack specifically written to accompany the film. This piece of choral music, “Voices of Light” by Richard Einhorn, is highly recommended.

The Passion of Joan of Arc isn’t one of those movies that you should watch because it marks a seminal moment in film history. It’s a film that’s better than almost everything else you’ve ever seen. It just happens to also be old, near lost, black & white, and silent.

yes. all of that. and more. see this movie.

This is what we call cool explanation of the point in interesting manner.

so kind of you to say, sir.

Well that’s wonderful. there should be golden words to explain it.