From his first proto-indie, art house feature (Sex, Lies, and Videotape) to his big budget Hollywood successes (Ocean’s Eleven) to his bizarre experimental stuff (Full Frontal), I’ve consistently queued up to see Steven Soderbergh‘s films.

It’s not that I love all of his movies, or even that I like most of them—some honestly are fairly unbearable. (Ché almost put me to sleep, and that was just Part One.) It’s that of all the directors working today, Soderbergh is the most game.

It’s not that I love all of his movies, or even that I like most of them—some honestly are fairly unbearable. (Ché almost put me to sleep, and that was just Part One.) It’s that of all the directors working today, Soderbergh is the most game.

While he has a style, Soderbergh doesn’t work from a pattern. One’s never quite sure what one’s going to get with his projects. Will his next outing be a kinetic, martial arts B-movie? An ensemble drama? A coming of age period piece? Maybe it’s an experimental film shot with non-actors? Hell, now he’s working on a biopic about Liberace for cable.

In the end, though, I’m pro-Soderbergh because I know what he’s capable of. In the latter half of the 1990s he directed a run of three films, each of which I include on my list of personal favorites. I own them all. Without hesitation, I would tell anyone to see them.

That’s what I’m doing now. Hey you. Go see these three films.

Whether you liked Erin Brockovich and hated Contagion, or loved Ocean’s Thirteen (and no, no you didn’t) and couldn’t stand Solaris, these three films will make all of those movies more interesting in retrospect. These three are visual mono-sodium glutamate to Soderbergh’s oeuvre.

With these films, Soderbergh swung for the fences and discovered the engaging aesthetic that now pervades his work. They represent the most impressive unbroken string of genius filmmaking since Scorsese made Raging Bull, King of Comedy, and After Hours; since Joel and Ethan Coen dished out Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing, and Barton Fink (and then, for the most part, started to suck).

Watch and learn.

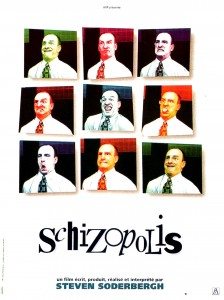

Schizopolis (1996)

You may have thought that The Master was a bold, grand film for daring to dance around the edges of Scientology. You’d be right, assuming you’d never seen Schizopolis (and cared for The Master).

You may have thought that The Master was a bold, grand film for daring to dance around the edges of Scientology. You’d be right, assuming you’d never seen Schizopolis (and cared for The Master).

To be fair, practically no one has seen Schizopolis. It barely saw the inside of theaters, being deemed too damn weird to appeal to the huddled masses. And it certainly is damned weird. It is, essentially, a comedic art film that looks at identity, communication, and something clearly intended to represent Scientology—a pseudo-religious self-help organization called ‘Eventualism.’

But what Schizopolis is about is debatable, assuming you like to have endless debates with insane people. The film starts with director, writer, cinematographer, and lead actor, Steven Soderbergh addressing an empty theater. Among other announcements, he says:

In the event that you find certain sequences or ideas (in this movie) confusing, please bear in mind that this is your fault, not ours. You will need to see the picture again and again until you understand everything.

Repeated viewings, however, may not help. They will be amusing, though, even if they cause your brain to skitter like a rabid squirrel.

The film, made for around $250,000, was shot without a script. Soderbergh made it all up on the fly or let actors improvise. Many of the cast members, such as himself, were also part of the crew. David Jensen who plays exterminator and television star Elmo Oxygen was the key grip. Betsy Brandt, who plays both the wife of and object of desire of the two main characters played by Soderbergh, is in fact Soderbergh’s ex-wife.

Oliver Stone? Never heard of him. Send meat.

Describing the plot of Schizopolis is a waste of time. The film is an experience, and one best enjoyed in company. It is not one of those art films that mopes around some lofty idea and expects you to dissect and interpret obtuse symbolism in a heightened dream state. It is one of those art films that includes a shot of a tree with a sign taped to it that reads, “idea missing.”

In the film, for example, a character writes the following letter:

Dear Attractive Woman Number 2,

Only once in my life have I responded to a person the way I’ve responded to you, but I’ve forgotten when it was or even if it was in fact me that responded. I may not know much, but I know that the wind sings your name endlessly, although with a slight lisp that makes it difficult to understand if I’m standing near an air conditioner. I know that your hair sits atop your head as though it could sit nowhere else. I know that your figure would make a sculptor cast aside his tools, injuring his assistant who was looking out the window instead of paying attention. I know that your lips are as full as that sexy French model’s that I desperately want to fuck. I know that if for an instant I could have you lie next to me, or on top of me, or sit on me, or stand over me and shake, then I would be the happiest man in my pants. I know all of this, and yet you do not know me. Change your life; accept my love. Or, at least let me pay you to accept it.

Things happen in Schizopolis. There is a story. More than that, I can’t really say. Except that I love it. It is completely unhinged.

When you’re watching it, though, there is one thing I’d like you to appreciate: this is not the work of a film student, or an avant garde artist, or someone trying to make a splash. Soderbergh made four features and a full-length documentary before making Schizopolis. This is a film he wanted to make—for himself, not for you—so he made it. Cannes didn’t care for it. Theaters wouldn’t play it. Screw ’em. He made it anyway, just for the love of filmmaking.

If you’ve ever complained about Hollywood being a business, or about films all being the same, or about a lack of creativity destroying modern cinema, then this film will shut your pie hole.*

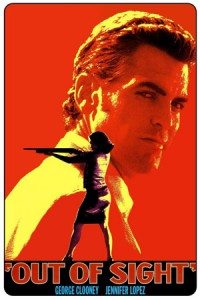

Out of Sight (1998)

After Schizopolis, you might think that Soderbergh would have felt drained of creativity. That he’d be moved to direct a bog-standard genre film. Something based on an Elmore Leonard book, starring some pretty faces. Something commercial and soulless.

After Schizopolis, you might think that Soderbergh would have felt drained of creativity. That he’d be moved to direct a bog-standard genre film. Something based on an Elmore Leonard book, starring some pretty faces. Something commercial and soulless.

He did and he didn’t.

Out of Sight is indeed from a Leonard novel. Elmore Leonard is one of those authors whose work is oft plundered for cinema; from Mr. Majestyk to 3:10 to Yuma to Get Shorty.

And pretty faces, sure. When Out of Sight was casting, George Clooney was basically just some hunk from E.R., known for being the Batman with rubber nipples. Jennifer Lopez—now one of the highest paid actresses around—had then been little more than a Fly Girl on In Living Color. Say what you will about JLo; in Out of Sight she’s spot on. Tough, quick, and rapturous. Clooney, well everyone loves him now. Out of Sight (and Three Kings) can take the credit. With those films, he transitioned from being Rosemary Clooney‘s sex symbol son to becoming our generation’s incarnation of Cary Grant.

So what is it that makes Out of Sight so much more than any given year’s contribution to the crime genre? It’s style. Soderbergh style.

Clooney, Zahn, and Rhames: in Lompoc, the color is yellow

This is the movie in which Steven Soderbergh began to play (along with editor Sarah Flack) with the stylistic elements that identify his work today. The use of color to distinguish time and location. Asynchronous sound—where voices and sound effects migrate between scenes so that we see and hear moments intermingled. Freeze frames, layers of flashbacks, careful use of score and audio cues: these things all combine to make what should have been just another crime caper into something supremely satisfying.

Because, really, there’s not too much to Out of Sight. In that way, it’s like Raiders of the Lost Ark. No deep message. Nothing ‘important’ to chew on. It is, at heart, entertainment—just flawlessly executed entertainment.

Soderbergh didn’t want to get trapped making small art house films, so he made a big commercial one.

I can tell you the story and you’ll shrug. Bank robber Jack Foley (Clooney) escapes from prison and tangles with Karen Sisco (Lopez), a U.S. Marshall. She chases him as he heads for a big score in Detroit, but he can’t help but chase her back, risking his liberty for her affection.

So it’s a crime film, and a chase movie, with comedic elements (Steve Zahn is great as Glenn), and a slice of romance. And the romance in Out of Sight is smokin’. Not in the skeezy, leering way you’d expect from a crime film; but in exactly the kind of way you want for date night.

See how the layering of asynchronous dialogue over scenes draws this whole sequence together? The way the freeze-frames catch your breath? It’s as if their falling into bed is inevitable.

I can, and do, watch Out of Sight whenever I need to just enjoy life. In it we get an exceptional supporting cast, including Albert Brooks, Don Cheadle, Catherine Keener, Viola Davis, Ving Rhames, Dennis Farina, and notably, Michael Keaton. In Out of Sight, Keaton plays Ray Niccolette—a character he also plays in Jackie Brown, which Quentin Tarantino had recently filmed and which is based on the Elmore Leonard book Rum Punch. That’s the same role in two otherwise unrelated films. Just a neat bit of trivia for you.

Watch Out of Sight and see what Soderbergh does with a big budget. Experience how deftly he locates you in time and space with color and sound. Let the small moments sink in. Leap around from high tension to deep romance to clever comedy without feeling disjointed or lost. Then, when it ends, want more.

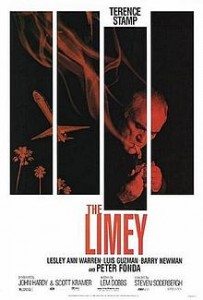

The Limey (1999)

Having proved that he can do art house madness and big budget entertainment, Soderbergh finished his trifecta by making what I think is his best film. It is, in the words of Goldilocks, just right. Not as arty, small, and perplexing as Schizopolis, nor as mass appeal and digestible as Out of Sight.

Having proved that he can do art house madness and big budget entertainment, Soderbergh finished his trifecta by making what I think is his best film. It is, in the words of Goldilocks, just right. Not as arty, small, and perplexing as Schizopolis, nor as mass appeal and digestible as Out of Sight.

The Limey as a film is like its protagonist: intensely focused. The great Terrance Stamp plays Wilson, an English ex-con who comes to California to find out what happened to his daughter, Jenny. He’s been told she died in a car wreck, but he isn’t exactly a trusting fellow.

Like in Out of Sight, Soderbergh relies heavily on flashbacks and asynchronous sound here. Adding another layer to Soderbergh’s use of disjointed time is Stamp’s back catalogue. The black and white footage used to illuminate Wilson’s early years in The Limey is actually from Ken Loach’s first film, Poor Cow, which featured Stamp.*

To the dismay of screenwriter Lem Dobbs (who also wrote Soderbergh films Kafka and Haywire), much of the script was pared away to leave Wilson front and center—and yet still hard to know. In the way of ex-cons, Wilson reveals little. What we learn of his suffering shows on his face.

He has failed his daughter time and again. Now that she’s dead, he’ll do everything he can to absolve himself of that guilt.

Wilson gets his teeth into Jenny’s boyfriend, a 1960’s slick record producer, Terry Valentine, played by Peter Fonda. Supporting characters remain hazy and peripheral (Luis Guzman stands out), but each feeds into the desperate drive Terrance Stamp etches into his every action. In story, and in its feel, The Limey reminds of earlier revenge classics like Get Carter and Point Blank.

Wilson gets his teeth into Jenny’s boyfriend, a 1960’s slick record producer, Terry Valentine, played by Peter Fonda. Supporting characters remain hazy and peripheral (Luis Guzman stands out), but each feeds into the desperate drive Terrance Stamp etches into his every action. In story, and in its feel, The Limey reminds of earlier revenge classics like Get Carter and Point Blank.

The Limey is an intense picture, but its knife-like focus can’t cut through the buried emotion that draws Wilson—and you, if you’re human—on. He is, in the end, chasing something much more complex than vengeance.

Like Schizopolis, The Limey is unhindered by the fat fingers of the money men. Like Out of Sight, it’s technically stunning. The story takes you exactly where you need to go. You cannot stop it. The Limey is inevitable. It is fucking coming.

Unsurprisingly, The Limey was also a box office disappointment. It took in less than a third of its costs. That’s alright, though. With his three best films all failing to impress the accountants, Soderbergh pivoted to make Erin Brockovich, Traffic, and the massively successful Ocean’s Eleven.

I’ve enjoyed quite a bit of his other work since then, and found much of it impressive in one way or another. For my money, though, these three easily top the bill.

I think I’ll go watch them all again.

* Speaking of weird Soderbergh films and multiple layers of Terrence Stamp, Full Frontal is an oddball Soderbergh opus that includes a cut away to scene of Mr. Stamp, as Wilson, on the airplane from The Limey. Out of nowhere, basically, just boom: there’s Wilson on the plane, as Julia Roberts and Blair Underwood act as actors playing actors playing actors.

Full Frontal is not as nutsy-cuckoo as Schizopolis, but it’s interesting in the same way, with a fascinating cast of Soderbergh irregulars, and it’s worth watching. It is also, for what it’s worth, described as an unofficial sequel to Sex, Lies, and Videotape.

As Soderbergh said of the Limey, it was Get Carter as if directed by Alain Resnais.

I really like all of the scenes in Full Frontal, which is why that movie appeals to me. The scenes don’t actually add up to much of a movie, of course, but taken as individual little pieces, it’s good stuff.

Oliver Stone? Never heard of him. Send meat.

Generic response.

Wait, there’s someone here that *hasn’t* seen Schizopolis?

What kind of goddamn riffraff are you attracting to this blog?

Also, Che, pt 1 is pretty damn dull, but pt 2 was much better.

I honestly think the point of Che Part I is to show how dull and normal the man was and thereby explode the cult of personality around him. Which, I suppose, is an interesting thing to do. It just made for a seriously dull film.

I just watched Che Part Two. It was not much better. I am very glad there isn’t a Part Three.

Yes. Agreed.

I recently showed the Mrs. “Out of Sight.” I remembered it more fondly than I experienced it this time. Performances were terrific. Look and design were all exceptional.

But the turn in the trunk of the car didn’t work for me this time. I couldn’t help but think Soderbergh was forcing a character to behave in a way that went completely against her backstory. And it was a difficult pill to swallow and accept.

I ended up going with it. The wife did not.

“The Limey,” however, is easily his best film and perfect in just about every way.

Got to see “Schizopolis” again. Holy crap did I almost black out from laughing when I first saw that one.

Interesting. I’ve never questioned the trunk scene. I think Sisco doesn’t fall for Foley in the trunk. She just doesn’t hate him; he’s not loathsome, as she expects. Her affection for him surprises her. She can’t really explain it and is embarrassed by it. And that all feels right to me. Plus she tries to shoot him at the end of that scene, right?

It’s his reaction to her that throws her off-guard and makes her second guess herself.

And it isn’t particularly contra to her backstory; it’s just contra to the backstory we expect her to have. She has a history of making rash romantic decisions. More than that, we don’t know.

See the scene in the morning at the hotel, where she questions herself, her motives, and his motives. She isn’t sure of what she’s doing at all.

She remains torn the entire film. That’s part of what makes it a great story for me. She’s chasing him, but also trying to wrestle her feelings. We don’t always love the person who’s most appropriate for us.

It’s the kind of love story where the happy ending is your girlfriend arresting you and hoping you manage to escape.

But no. It’s not as good as The Limey. The Limey is gold.

He seems to like to challenge himself. I don’t know if it’s the correct term but I consider him to be a great craftsman. He has a great ability to elevate what could normally be straight up bland by the numbers Hollywood movies and make great entertainment. Recently I watched Contagion and Magic Mike, and enjoyed both, neither is particularly amazing but both are above average multiplex movies and I think much better than they would have been in the hands of most other directors.

I’ve always liked Soderbergh because of the fact that he seems to just change things up all the time. He makes me wonder what Scorcese of Spielberg (or Bay!) would do with a a million dollars a couple of weeks to shoot something.

Not watched The Limey or Schizopolis, although I’ve had The Limey on my watch list for a long time. I think Out of Sight is close to perfect, I just text my Mrs to ask if she’s watched it. Good reason to see it again.

I remember liking Che Part one when I watched it. Still not watched part two though.

Yup. He seems to approach projects as if he’s just looking to have a good time with what he finds in front of him. He’s willing to experiment in a way that someone who is committed to their reputation rarely is.

I haven’t loved any of his recent work. I thought Contagion was dull and unengaging. Haywire was fun to watch but hardly a masterpiece. Haven’t had a chance to see Magic Mike yet. I think the last of his films I’ve really enjoyed is Ocean’s Eleven, and that’s just fluffy fun. I guess The Informant! was a good laugh.

I just watched Che Part Two last night. While it’s been a long time since I saw Che Part One, I felt almost exactly the same after watching the second part as I did the first: bored. Soderbergh is exploding the cult of personality around Guevara by showing how real he was. He’s just, in the end, a man. I thought the events of Part One were much more interesting than the events of Part Two. It was never quite clear to me from the film how many people were actually involved in the Bolivian revolution—it seemed the answer was about 30.

I’ve been on a Soderbergh kick lately, and came across your blog as I’m finishing reading Getting Away with It (Soderbergh diary entries interspersed with interviews of Richard Lester). I re-watched Out of Sight recently and will soon be watching The Limey, for only the second time. I’ll have to track down Schizopolis, too.

Your synopsis of Out of Sight is spot on. I love the fantasy sequence of J.Lo joining Clooney I’m the bath, as a cinematic solution for showing how (and how!) Karen is thinking about Foley after the abduction. In addition to Soderbergh, screenwriter Scott Frank deserves much credit for how well the movie works. He invented scenes not in the novel, such as the call from Foley to Sisco at her father’s home. There is such an economy of storytelling in that little scene! I think the movie is a rare example that surpasses its source material.

One point of fact: Rosemary Clooney was George’s aunt, not his mother. So that passage should read, “Rosemary Clooney’s sex symbol nephew.”