What can be intelligently said about Django Unchained? If we leave aside all of the fanboy love and the howls of the haters, what sense remains?

What can be intelligently said about Django Unchained? If we leave aside all of the fanboy love and the howls of the haters, what sense remains?

Is this what you ask of me?

If you are among the healthy ranks who think Quentin Tarantino a genius, then you will likely enjoy the film’s rambunctious dialogue, exuberant displays of blood-letting, and knowing humor. If you are among those who do not, you will probably find it insipid and morally dubious.

But whether or not Quentin Tarantino is a genius is a point with little meaning.

The word “genius” doesn’t even really have an objective definition. A genius, by the dictionary’s reckoning, is one with “exceptional intelligence or ability.” Exceptional being a fairly low bar to vault. Who is a genius ends up being a matter of perspective. A question of respect.

So: do we respect Quentin Tarantino? Do you think that he is attempting and succeeding at artistic endeavors (exceptionally) or is he a just a galoot who knows how to raise a stylish ruckus?

Perhaps you can sense which way I tend from my phrasing.

I have not seen the brilliance in QTs body of work that others do. That does not necessarily mean it is not there, though, as some of these others hold opinions I respect. Perhaps I am just looking with the wrong eyes?

I’ve liked some of Tarantino’s films. Some of them I’ve even liked after the second viewing. Lately, not so much. And so I’ve gone digging to see what his proponents have to say in his favor. FILM CRIT HULK, for example, talks about Tarantino’s use of dialogue to create tension. I see that. A reasonable point, HULK.

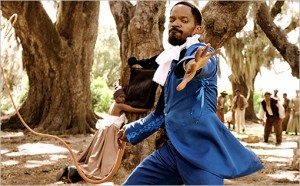

In fact, one of the scenes I liked best in Django Unchained was a tension-inducing post-prandial skull-measuring scene in which Leonardo DiCaprio’s Calvin Candie turns the tables on our unlikely heroes: Jaime Foxx as Django and Christoph Waltz as Dr. King Schultz.

Making a point about the inferiority of slaves, Candie removes a ghostly white skull from a velvet case, saws its back off, and brandishes proof of the African’s weakness. All while ramping up his monologue to a violent denouement.

Why, precisely, Monsieur Candie had saved his longtime servant’s skull in a special case and chosen this moment to destroy his creepy memento was not made clear, however.

Candie had previously mentioned his interest in phrenology, so the ostensible subject of his rant has roots in the story. But the rest? Candie is angry at being conned, even though he’s lost nothing tangible and was in no danger. His melodramatic riposte in this scene, then, is contextually cartoonish and, worse, comic.

It’s a good scene, as long as you don’t expect it to make sense as part of the film.

See, Django wants his wife back. Candie owns his wife. Rather than just offering to buy her, as she’s a slave, Django and Schultz concoct a bizarre plot in which they pretend they want to purchase a Mandingo fighter (a slave who will participate in fights to the death) for an exorbitant amount so they can casually tack on the purchase of Broomhilde (Django’s wife, so named for oblique reasons). Except, oh no, clever head house slave Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson) gets wise and monkey wrenches.

End synopsis. Back to perspective.

Where HULK sees elegantly constructed scenes, I see scenes left orphaned by an intoxicated plot. Why have Django and Schultz constructed such an intricate ruse? If Candie will sell one of his prized Mandingo fighters for an exorbitant sum, would he not be quicker to sell a disobedient slave for substantially less? And although Django and Schultz never intended on paying any exorbitant sum, when they are forced to anyway it seems to cause them no pain whatsoever. $12,000 is taken from Schultz’s billfold in cash on the spot. The bills seem to represent a small fraction of what the Doctor carries around as spending money.

And why, I wonder, upon discovering the ruse, does Candie even care? His complaint, that they’ve wasted his time, is petulant (and in character) but it’s certainly not worth a whole hullabaloo with guns and skull sawing. And white cake.

But again, perspective. If we are inclined to credit Tarantino, we accept these plot devices as within the genre’s fast and loose style. We enjoy the ride.

But I don’t and I didn’t.

To me, looking at the structure of the story, trying to determine what—if anything—Tarantino is attempting to say, the fact that a few of the dialogue scenes build tension elegantly is beside the point. How can I care that a scene unconnected to reality builds tension? Especially when there is also a scene in which a mob of men stops to complain at length about how difficult it is to see whilst wearing Klan-type masks? That’s 10 minutes of out-of-place KKK comic relief in a movie about slaves, men torn apart by dogs, and implied rape. As if to say, “Hey guys, don’t take all this slavery stuff too seriously. It’s just a lark. Those guys! They sure were dopes, har har!”

And then I think about what I have come to the theater expecting. A movie. A fun one, presumably, but with Tarantino’s brand of violence. A film about slavery. An exploitation picture in the spaghetti western style. So, something not serious, but which appropriates serious topics for subject matter.

What is that? Like a pop-up book about birth defects? Who makes such a thing? Do you have something to say or not, Quentin? Or is the drama of the world just grist for another of your adolescent fantasies (which you should have gotten out of your system after your personal dream-come-true film, True Romance.)

Django Unchained is a cartoonish revenge doodle that is no more about slavery than Inglourious Basterds was about the Holocaust. Django Unchained utilizes the slavery era as a setting and employs matching set pieces mainly to justify its extensive use of the word nigger. Otherwise, forget it. It’s got nothing of any heft to say about slavery.

Picture, if you will, the scene early on in which we cross a plantation filled with well-dressed slaves lounging about on swings. Literally; they’re swinging under the dogwoods, or whatever. But at the same time another slave on the same plantation is being whipped for dropping an egg. Is that a statement? What could it mean? That slave masters are capricious? Or did Tarantino just want to show attractive black women in period dresses lounging about in the sunshine (so we could then watch them get their clothes torn off for a whipping)?

Suddenly I feel a little nauseous.

Here’s a much stronger example of the film’s lack of moral sensibility, one which SPOILS the ending of the film.

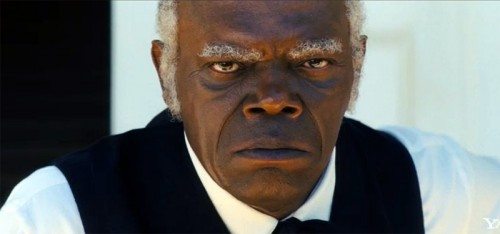

This slave-revenge fantasy, in which Django rescues his stolen wife from a Mandingo-fight-staging, phrenology-espousing, release-the-hounding, slave-owning, semi-psychotic, sister-loving, pretentious shithead has one clear villain. That villain is the shithead’s house slave, Stephen, played by Samuel L. Jackson. It is Stephen who gets fetishistically knee-capped and who goes down (or up, as the case may be) with the plantation. It is Jackson who must be killed for the film to finally end. For vengeance to be Django’s, as they say.

It is Jackson’s race-betrayer slave whose death we’re meant to savor watching. We don’t much care about the slave owners when they get got.

DiCapario’s Candie—the shithead—gets shot much earlier, casually. Killed because, as Christoph Waltz’s Dr. Schultz says “I couldn’t resist.” Bang, dead, done. The film goes on for another half hour. The other bad men are dispatched with all the grace of Gallagher having a go at watermelon and with the same amount of splatter.

Plus, in the real world? No such thing as Mandingo fighting. Slaves in America were not set against each other to fight to the death in any organized way. So, you know, Tarantino just put that central conceit in his movie for fun. So we could enjoy watching men tear out each other’s eyes—as they literally do in Django Unchained.

I appear to be losing perspective. Or gaining one. Is historical accuracy even important here? I hope not. Relax. Have fun. Enjoy watching people get puréed by rifle blasts.

Do not go to see Django Unchained as Spike Lee’s date or you will surely be unable to shut him up. Do not even go in prepared to think about anything other than what cinema is and has been and whether or not style can qualify as substance. Tarantino’s style, that is. Something Tarantino clearly has. He invented it and you bought it, whatever it might be and regardless of how original it is.

Django Unchained is a spaghetti western. It is a tribute to and extension of films which were themselves tributes to and extensions of films. Those films, the Carbucci Django films, were about violence and heroics in a world of muddled morality.

So on that score, Django Unchained hits home.

Job well done?

Does Django Unchained hold any message? If it does, I don’t immediately see what that could be. Carbucci’s Django didn’t mean anything either, though. It didn’t even really have a plot. There was something about gold, or revenge, or both, but then neither. It was mostly just people being violent to one another somewhat stylishly. And so it’s a cult film.

Does Django Unchained hold any message? If it does, I don’t immediately see what that could be. Carbucci’s Django didn’t mean anything either, though. It didn’t even really have a plot. There was something about gold, or revenge, or both, but then neither. It was mostly just people being violent to one another somewhat stylishly. And so it’s a cult film.

Did the pinnacle of spaghetti westerns, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly have something to say? Assuredly. It was illustrative of the effects of greed on men. The situations it presented were remarkable, but not unbelievable. Blondie, Tuco, and Angel Eyes took Dr. Schultz’s advice and stuck to character throughout the entire film. They reacted to situations honestly and found drama and humor within those plot-driven situations. And style? Each shot, each scene will make you weep. Not at the expense of story and character, because of it. That’s why that film is a classic. That’s genius.

But Django Unchained didn’t want to be The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. It wanted to emulate something lesser and it did so successfully, I guess. It even started with the original Django theme song—not even a cover version; the actual song from the ’66 film. Then, for some reason, Tarantino started spinning hip hop.

So that’s my perspective on Django Unchained. It, more than anything, reminded me of Exit Through the Gift Shop‘s Thierry Guetta. A bunch of hype over nothing and all the real ideas were someone else’s anyway.

UPDATE: Could it be? Is it possible to watch the same film two completely different ways? I’m not yet sure but I’m very grateful to the patrons at Bad Ass Digest for attempting to change my thinking on Quentin Tarantino. Read their well-considered opinions here.

UPDATE 2: If you have found this post because you are searching for information on phrenology, here is all you need to know: it is bullshit. “Phrenology has been thoroughly discredited and has been recognized as having no scientific merit.”

Though I’ve seen few of Tarantino’s films and am thus almost wholly unqualified to render judgment, I heartily agree with you. In his work I see a lot is style and not much substance. I see a juvenile, reflexive need to shock–the more casually, the better. I see a dude well into middle age who is still obsessed with being ‘cool’. Thanks for getting into some details and making some of these points.

you’re welcome. you should check out the Update link just above to hear what the die-hard fans cite as reasons to rethink Tarantino.

are they right? it’s hard to say. either way, it’s food for thought. and i try to keep an open mind.

I agree wholeheartedly with Mr. Bricca. Although I would also add that Tarantino’s films are also all marked with troubling racial overtones. (I didn’t say “undertones,” because everything in his films blare at the same Nigel Tufnel 11 setting)

Tarantino’s strange — and frankly upsetting — fascination with Black slurs is at best odd and at worst hateful. And they often lack any context or purpose in the scene, other than to be naughty. He sort of reminds me of the stupid 12 year old suburban white boys I knew back in Boston who used to get a superior rush being racist without fully understanding the ugly things they were saying.

Of course, Mr. Tarantino is not a 12 year old boy. He fully knows the power of those words, so it calls into question just what the hell he’s really trying to do. I guess sell tickets. I guess generate press. And I guess he’s successful at both.

But that’s hardly a difficult task, if all you’re selling is pornography. I mean, pornography sells. In fact, it’s the easiest way to make money in the world (as long as you’re able to get over the moral hurdle of actually making porn).

And that’s all his recent films are — porn. Violent porn. Racist porn. Hipster porn. These films have no purpose other than to excite and titillate.

In the end, Tarantino has more in common with Kim Kardashian than Martin Scorcese. He’s not making challenging movies. He’s making the cinematic equivalent of a sex tape, followed by carefully constructed outrageous interviews that generate the right amount of press.

Predictably shocking.

Which isn’t shocking at all.

yeah. i’m in the midst of a conversation with people who are claiming he does all this deliberately to stimulate a meta conversation.

which i’d immediately dismiss except some smart people are involved.

but then i can’t yet correlate my impressions of his work with the words i’m hearing. and if the communication doesn’t come through—even when one is listening—is it communication?

or is QTs work an acquired taste, like lütfisk or heroin or something? once you get it, you’re hooked, but until then it seems the people enjoying it are out of their fucking gourds.

honestly don’t know. still open to being convinced i’ve been wrong about him, but… i keep circling back to this fact: his films haven’t communicated anything intelligent to me on their own merits. if i need to be led down the path to taking him seriously, he needs to own a healthy chunk of that failure. and other directors manage to write a meta story with comprehensive themes without offering up stories that don’t stand up on a surface level.

people say his films are meant to be watched with awareness that you’re watching a movie. if that’s so, i suspect i’ll never love them. appreciate them on one level; maybe.

it comes back to perspective.

You are right on the money regarding the ridiculousness of the entire ruse surrounding the buying of the mandingo fighter. That entire scheme made absolutely no sense to me. If all they wanted was Django’s wife, why not come right out and say it and pay for her? Why the deception? It seems to over-complicate matters needlessly. And Candie’s reaction once everything was revealed was also way over the top as you said. In my book, QT has created only 2 good works: Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill. That’s it. And I’m only giving him credit for Kill Bill because the Pai Mei character was so awesome!