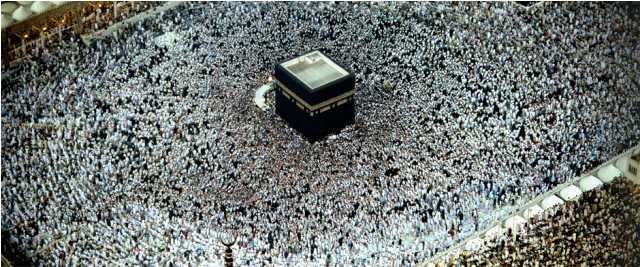

There are shots in Samsara (’12) of places you can’t believe exist on Earth, like the stone temples in the jungles of Myanmar that look like a CGI landscape from an ancient, otherworldly fairy tale. Other images, like the shots of the Kaaba in Mecca, you can believe, but to see millions of white-robed worshippers encircling and praying in detailed 70mm is enough to cripple one’s brain. It’s ominous and beautiful. Which is not a bad description of the entire movie.

Samsara is cinematographer/director Ron Fricke’s follow-up to his very similar Baraka (’92). Both movies are stuffed full of beautiful imagery, and for that alone they’re worth seeing, preferably on a big screen. All told, I think Samsara is an improvement on Baraka, which despite its beauty I always found terribly dull. Samsara moves along more easily and naturally.

The word samsara refers to birth, death, and rebirth. Sort of the circle of life, let’s say. But without the singing lions. It’s about impermanence, as signified in the movie with the rather too obvious scene of monks creating a sand mandala. Which is shot in stunning, colorful close-ups, to the point where you can see individual grains of sand piling up to form images. It’s just that it comes at the beginning, meaning the end of the movie is guaranteed to show them wiping the sand away, because that’s like life, man, it comes and it goes. Maybe they should have filmed at Burning Man and ended the movie with the big neon guy going down in flames.

So like Baraka, which features such moments as a giant Brazilian tree being toppled by loggers followed by a cut to the stern face of an Indian, Samsara isn’t subtle. Particulary unsubtle are the sequences showing vast chicken and pig rendering factories, which are beyond ghastly. I suppose that’s one way to feature the death angle of the movie.

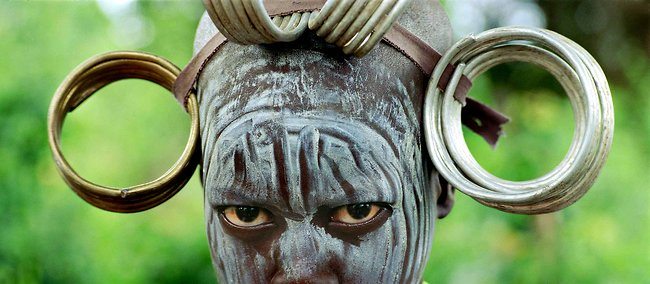

Samsara is also big on masks, and people making masks of their faces. The opening shot of the film shows three Balinese (?) dancers whose smiling faces are like frozen doll masks. Then there’s the performance art sequence, where a man at a desk smears clay on his face, paints in eyes and a mouth, tears away the clay, builds another more insane face, tears that away, and over and over again, ever more violently. That was neat.

Like Baraka, the weakest aspect of Samsara is the music, this kind of wallpaper-like new-agey background that adds nothing. Fricke edited the movie silently and gave the finished sequences to the composers Michael Sterns and Lisa Gerrard, to which they composed songs. Which eliminates cutting the movie to fit the music, not at all a bad idea, but in this case the music and movie don’t fit together especially well. Not that it’s jarring or at odds with the images. If anything it’s that the music is too smooth and unobtrusive. It’s background.

Part of what I find disappointing about Fricke’s work in Baraka and Samsara is how poorly the two movies compare to Godfrey Reggio’s Qatsi trilogy, Koyaanisqatsi (’82), Powaqqatsi (’88) and Naqoyqatsi (’02). Fricke shot the first and best of these, Koyaanisqatsi, and went on to recreate many of its iconic images for Baraka. In Samsara he even revisits a number of locations used in Koyaanisqatsi. The difference is that Koyaanisqatsi tells a story in as articulate a way as any normal, narrative feature. Watching Koyaanisqatsi you’re left with the impression that to switch around any of the shots would be to destroy the movie, just like you couldn’t rearrange scenes in, say, The Godfather and still maintain a coherent narrative.

With Baraka and Samsara, this feeling isn’t there at all. Yes, the movies have certain sequences that go together, certain ideas that are explored by a series of edits, but on the whole, with both movies I’m left with a feeling that one could rearrange the images at will and not affect the story in any way. Because there is no story. There is a theme, and that theme is explored. Which is fine, having no story. It’s purposeful. The movie is meant to leave an impression. One is pulled along in Samsara by the endless series of jaw-dropping shots. One is not pulled along by how each shot leads into the next. So the hope is that as long as each shot is in itself compelling, you won’t grow bored.

Koyaanisqatsi also features the brilliant music of Philip Glass. He composed the music while the movie was being edited. So the editors fed off the music Glass was creating while Glass fed off the work of the editors. The resulting effect creates a blend of music and image so complete that one is in danger of confusing one for the other. The music is the image and the image is the music. They are intertwined completely.

But my giant Koyaanisqatsi post is for another time. Meanwhile, Samsara, despite not ultimately adding up to much beyond its constituent parts, is absolutely worth seeing for those constituent parts, especially if you get a chance to see it in a theater. Images like these, shot in glorious 70mm, are not to be found anywhere else. If you’re a bigger fan of Baraka than I am, you will no doubt like it that much more.

Speaking of Koyaanisqatsi, the whole trilogy comes out on Criterion BluRay tomorrow, which is great, considering that at one point release of Koyaanisqatsi to home theater was tied up with legal issues for years.

I still remember paying close to $200 bucks to get the limited edition dvd that IRE put out back in the late ’90s when you couldn’t get a copy of it any other way (legally, at least).

“If we dig precious things from the land, we will invite disaster.”

“Near the day of Purification, there will be cobwebs spun back and forth in the sky.”

“A container of ashes might one day be thrown from the sky, which could burn the land and boil the oceans.”

yes. i will be getting that blu-ray set.