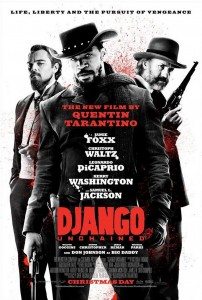

Seems like these days you can’t throw a rock at the internet without knocking Quentin Tarantino’s dick out of someone’s mouth. The arguments raging on movie nerd sites range all the way from “Tarantino is a genius, yes, but is he actually the best director of all time, or only in the top three?” to “Is Death Proof the only Tarantino movie that isn’t perfect, or is it in fact as perfect as all the others?” It’s apparently a foregone conclusion that the man must be spoken of only in hushed, reverent tones, and be compared favorably to Kubrick, the Coens, and, while we’re at it, Ingmar fucking Bergman.

I find this reverence hard to comprehend. Apparently I am alone in finding his Nazi-revenge-porn-fantasy-cartoon-death-parade Inglourious Basterds to be not only a poorly written, inept, unfunny slog, but morally bankrupt besides. I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a movie where slaughtering people was done so joyously. Which I know, Nazis. Yay! Kill ‘em all! It’s a fantasy revenge porn movie! Whee! And so on. But I’m sorry. I have a hard time finding glee in massacres.

Am I some kind of boring scold on the matter? Hardly. The Wild Bunch? Sign me up. Romero’s Dawn of The Dead? One of the best movies ever made. Hell, I even love Reservoir Dogs. In all of these movies, death might be plentiful, it might be absurdly over the top, but it still means something. It’s still death. It’s not fun. It hurts. You can thrill to it, in a sense. The ending of The Wild Bunch is a ballet of dancing, machine-gunned bodies. It’s beautiful to watch, in a cinematic sense. It’s what Tarantino is going for too, only somehow he takes it to a different place. It’s not just the glee of showing these kinds of massacres in a cinematically beautiful way, it’s that in everything he’s made at least since Kill Bill, the murders themselves are meant to be reveled in.

Film Crit Hulk, in his top ten of 2012, where he names Django Unchained number 2, mentions the final theater massacre in Inglourious Basterds, saying it’s meaningful because as it’s happening, we too are in a theater watching it happen. We sit in a theater enjoying Nazis being killed while they sit in a theater enjoying a violent movie. I’m not sure what to say to that aside from, “And? So what?” I don’t see how that’s commenting on anything. Is Tarantino saying we’re just like the Nazis for getting off on death? If so, good for him. But I don’t think that’s at all what he’s saying, and I’ve never heard anyone who liked the movie suggest anything of the sort. People like the movie because it’s a wild cartoon revenge fantasy where Hitler and his minions are joyfully—and hilariously!—massacred.

When people say that the violence in Inglourious Basterds or Django Unchained is supposed to make us reflect on why we enjoy that violence, that Tarantino is interested in the exploration of cinematic violence not in a visual and visceral sense, but in a philosophical one, I have to say bullshit. I don’t see how the “text,” i.e. the movies and nothing but the movies, support these kind of claims at all. Now of course you can read anything you want into anything, no matter what’s presented to you. But where in Tarantino movies is this deeper meaning suggested?

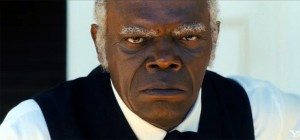

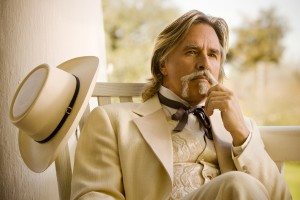

Django Unchained is very similar to Inglourious Basterds. It’s another revenge-porn flick, this time with slave owners as the Nazis, although in an odd turn, the man who’s presented as most evil of all, the one who’s saved until last, who’s tortured by being shot multiple times in the knees, and then blown up by dynamite, is himself a slave, Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson). But he’s comfortable in his slavery and supports his white master Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), which as far as the movie is concerned makes him more evil than even the rich, white slave-owner.

I’m not sure what to make of this, or what Taraninto wants me to make of it. Nothing? Bad guys come in all colors? The movie makes a point of wondering how any slave, no matter how well-treated (as in the case of Stephen, who runs Candie’s household, says what he wants, and is comfortable sipping brandy in the library), could not do his damnedest to escape and kill his captors at every opportunity. So one must assume that Stephen embodies this kind of weak thinking. His failure to rise up, to resist in any way, marks him as worse than the white man himself.

Which if we follow that logic even one step further, we end up someplace where–what, we’re supposed to blame slaves for their being slaves? That Django represents what all slaves should have done? Only how did Django find himself in a position of power? He was granted it by a white man. Hm.

As it happens, I don’t think Tarantino is aware of this at all, consciously. Because in his movies I see a lot of surface, and little depth. I think my above reading of Stephen and his fate has nothing to do with Tarantino’s intent. Likewise, reading into movie theater massacres a greater, deeper intent is equally pointless, because nothing in these movies suggests that Tarantino intends any of it. What does he intend? I have no idea. Maybe he’s a brilliant filmic theoritician. I can’t look inside his head. I can only look at what he puts on-screen.

In fact an artist’s intent matters not at all. All that matters is what’s on-screen. My point is that in a movie with nothing deep on display, you can read into it whatever you want. His fans, not surprisingly, read nuance and depth. Anything negative they don’t see at all.

The other issue for me with Tarantino as a filmmaker is that all of the above is beside the point. If I don’t enjoy watching the movie, I don’t care how much discussion after the fact it engenders. And I did not enjoy watching Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, Death Proof, or Kill Bill (yeah, I know, why do I keep going back? Hope springs eternal, my friends!).

Tarantino is not a good screenwriter. Does he write good dialogue? Sure. Great, even, at times. And that’s all he writes. That’s what people respond to. That’s why people love his characters. They talk real purty. It makes them memorable. The thing is, screenwriting is not just dialogue. As any screenwriting 101 text will tell you, movies are structure. It’s how you string which scenes together that make a movie. All the pretty dialogue in the world won’t save a crappy story.

Tarantino seems to have one thing he likes to do, and he does it over and over and over again. He sets up a scene with two or more characters, where one is hiding something, where one person has something on the other person, where there is an imbalance of knowledge, and where one slip-up will mean violence and death. Then he has them talk for a good ten minutes. And so, tension. The scene ends with either an explosion of violence, or a sigh of relief when nothing happens. Is there any other scene in Inglourious Basterds? Hardly. Stringing these scenes together doesn’t make for much of a movie. There’s no pacing. It’s one long, talky scene after another. Above all, Basterds bored me. Yes, the opening scene in the farmhouse is a very successful example of a Tarantino Tension Scene (TTS). It’s a great start to the movie. But after that, each new iteration of the scene becomes more and more boring.

When his movies are criticized, Tarantino’s fans will always point to strong scenes like that opener. You can’t disagree. As scenes, they can be very entertaining. But the best scenes do something else in the best movies: they move the story, however weird or experimental it may be, to where it’s going. The best scenes function at their best as a part of a whole. Tarantino’s best scenes work whether or not you happen to see the rest of the movies they come from. They work as shorts. And in so doing, they fail at the more important job of working within a larger context.

Django Unchained, compared to the otherwise very similar Inglourious Basterds, is unusually linear for Tarantino. There’s not much in the way of senselessly long scenes having nothing to do with anything but his love of long, talky scenes. But they’re still in there, most notably the KKK scene, where a bunch of hooded jack-asses humorously lament the poorly cut-out eyeholes in their hoods. It’s kinda funny. Part of the humor comes from the scene existing literally outside the rest of the movie. The movie takes a time-out, this goofy scene plays, and then the movie resumes. This is not skillfull story-telling. It’s indulgent bullshit. It’s represents the worst kind of filmmaking, where showing off is more important than telling a story. Making fun of a bunch of stupid clansmen isn’t exactly rocket science. Fitting such a scene seamlessly into your story is.

Tarantino seems also to have a problem with plans in his movies. By which I mean the schemes his characters come up with. He’s so concerned with his dialogue that he forgets how much it helps to have plausible goals for your characters. Or semi-plausible. Movie-plausible, at least. In Basterds the basterds come up with a plan to murder Hitler and his henchmen in a theater while they’re all watching a movie. This theater is run by a woman who’s decided to murder Hitler and his henchmen by burning down the theater. Maybe this is a joke I don’t get? Or something? Their plan is to do the very thing someone else is already doing? Hitler will die even if the basterds didn’t exist or spent their time playing Yahtzee? Please someone tell me why that is smart or interesting or anything but incredibly fucking stupid? It screams “I want all my characters in one place killing Nazis! Go!”

In Django Unchained, there’s this nonsense scene where the bounty-hunter King (Christoph Waltz) explains to Django (Jamie Foxx) why they can’t simply go to Candie and offer to buy his slave Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), Django’s wife. Instead they come up with a complicated role-playing scenario involving their interest in “Mandingo fighters,” i.e. black men who fight each other to the death (which it seems Tarantino made up or else just borrowed from the movie Mandingo). Halfway through an interminably long dinner scene, Stephen (the evil slave) tells Candie that surely Django is married to Broomhilda, that she’s their real object, that they’ve been lying to Candie. Candie is outraged! A TTS plays out, ending with Candie selling Broomhilda for the same amount of money King offered for the Mandingo fighter. Which cash is taken from his wallet, where much more money remains. Are you with me here? Our heroes get exactly what they came for, and suffer only by having to endure DiCaprio’s scenery chewing speech about phrenology. This is not good story-telling.

What happens next? How may revenge be taken on the evil slave-owner when he gave them exactly what they came for? How about having King shoot Candie out of pique, knowing he’s going to be immediately cut down by Candie’s henchman? Well, okay. How does this make sense? Is it because King hates slavery so much that he just has to do it, his own death be damned? I guess…yes? Technically speaking, this sort of thing is called “fucking lame.”

Story-telling is not Tarantino’s strength, nor is the building of tightly written screenplays. This is why his movies are so unbearably long. He revels in his over-written scenes. Those are what matter to him. The overall story? It’s secondary to the joys of the moment.

Like I said above, I love Reservoir Dogs. It’s everything Tarantino’s later movies aren’t. It’s short, it’s powerful, the violence, while plentiful, feels real and painful, there’s great dialogue used not to show off, but to tell a very specific story, and there’s no wasted time. It’s his best movie.

Filmmakers live in the world. They make movies that however abstractly speak to that world and to the people in it. Whether it’s a western or science fiction or full of talking animals, movies are a reflection and meditation on this actual place in which we exist. Watching Django Unchained I realized that Tarantino makes movies soley in the world of movies. He’s not merely quoting other movies and other filmmakers. Tarantino’s movies exist as reflections and meditations on the world of movies. It’s like in The Player, where at the end we see the Bruce Willis gas chamber rescue scene in the “fake” movie-within-the-movie. That’s the movie Tarantino is making, every time out.

Django Unchained is the cartoon-within-the-cartoon. I imagine it’s the sort of movie Itchy & Scratchy would watch. It’s alternately horrifying and wacky, with no sense to the mood changes. Tarantino shoots it with all kinds of weird nods to spaghetti westerns: quick zooms into faces, jerky editing, flashbacks and flashforwards shoe-horned in almost at random. Is this for laughs? In Leone’s movies this kind of thing was a purposeful, expertly used style. It’s so wonderful one can’t help but laugh sometimes. This is not laughter at the movie being somehow bad, it’s the laughter that comes from delight at seeing a style unique and ballsy. Why does Tarantino ape these stylistic flourishes? I suppose those who adore him will say it’s done to place his movies in a kind of cinematic dialogue with his inspirations. Or something.

I think it’s that Tarantino loves the movies he references and imitates, and he wants everyone to know it. So his movies are movies about movies. Which has resulted in his movies becoming more and more removed from anything real or meaningful. Django Unchained is being hailed by his fans as another masterpiece, just like Basterds. I agree that it’s basically the same movie. Beyond that…I think it’s time to watch Reservoir Dogs again.

This isn’t his first film, as you well know. So why are you so very unhappy with what he delivers?

I certainly knew exactly what I would get with this movie and as such wasn’t disappointed at all.

This is what QT has decided to give us over and over. He isn’t going to change the $$$$ formula. Just give up hoping for more and enjoy the “style” or simply skip him all together.

This isn’t bad advice. The thing is, I like seeing and thinking about movies, especially those made by writer/directors, and especially those it seems the rest of the movie obsessed crowd thinks are the BEST THINGS EVER. So I see Tarantino movies.

People who love him tend to get all up in arms if you only talk about liking the style. They seem to think there is much more going on in there. So I keep going back, trying to see what they see.

But you’re right. Tarantino delivers the same thing time and again. When the next one comes out, maybe I’ll be smart enough to skip it.

I’m with the Supreme Being on this (who wouldn’t be, he *is* co-terminal with space and time). Except I don’t think that Django is “Tarentino as usual”

I have a motto in my writing – “if your characters all sit down, you’re doing something wrong.” I think its essential to concentrate on moving forward.

I started by writing off-off-off-off-off Broadway plays (any more *off* and be performing on a space elevator). And I developed a theory, that the goal of the story is simply to get the main character from “stage left”

There were *tons* of things I loved about Djago (the opening scene with the slave traders was awesome). But man, I was amazed at how many scenes involved people SITTING DOWN. I’ve always thought of QT as a pretty restless creator— Pulp Fiction is an amazing, hyperkinetic pomo challenge to conventional film-making.

Django ain’t. Its a whole *lot* of people sitting down. Even if the dialogue is cool, who cares? The story isn’t advancing.

And the whole plot hangs on rescuing Django’s wife. Which they can actually do with no bloodshed. But for some reason Christoph Waltz decides to start trouble. Its not a very compelling plot when all your characters have to do is pony up 11 grand to save the girl. Its not a rescue operation, its a live-action Ebay session.

Hmm. As it happens to be more often than not, I respectfully disagree. However, not wholeheartedly — I did like your caption for the image from Resivoir Dogs.

well at least there was that. we hate for anyone to go home completely disappointed…

It’s odd. On one hand, I agree with many of the points made here. All of your criticisms seem valid to me. But on the other, I just loved D.U. I found it to be a very enjoyable movie. Sure, the story wasn’t that complex; but nonetheless, I loved D.U. But that being said, I think I feel the same way you did about U.B. I didn’t enjoy U.B at all. Perhaps it was the combination of the excellent actors, the great dialogue, the interesting setting, and the fact that I’m a pretty big spaghetti Western fan.

Do some further research into analysis essays on other QT films, theres a lot more to them. You just need to scratch below the surface.

I’ll give you an example in DU. In the opening scene were given a upward panning shot of the the horse’s leg being ridden by the slaver with the slaves legs behind it which may at first have been percieved as another horse. See what I am getting at? Another example is when Django gets some new garb as well as a new saddle for his horse, this might be a concidence, but I believe it is intentional. The final evidence is when he is riding the horse without a saddle back to Candi land after tricking his strangely Australian captors. This could be percieved as that Django has nothing left to loose, and is free of his role as acting as a mandingo expert. In the same way the horse is uncontrained by any straps or a saddle. With this symbolic nature between the slaves and the horses, I believe QT was trying to make a comparison between domesticated animals and the negro slaves such as treating them like a tools and stamping out their its wild nature.

Thank you, and please feel welcome to criticise this theory.

That all seems sensible, Ross. I think the issue is the disconnect between surface story and subtext. Sure, if you look there may well be intentional meaning about slaves and beasts of burden. But most people won’t look. They’ll see a film about slavery in which the real villain is Sam Jackson’s house slave, not the pompous Candi who’s portrayed as a fool.

So while I understand Tarantino has impressive subtext he obfuscates it with a lack of care in his primal text. Theme is important but it has to serve story and not vice versa. His films are all nods and winks. Sometimes I care to divine his meaning, but not often. Usually it’s just tedious. And… Slaves are like beasts of burden? Hm. Not too deep or original a message is it?

Ask instead what most people take away from DU. And compare it to a film like, say, Dr Strangelove where the subtext expands the story instead of hiding beneath an oddly fractured one.

Yes, well it’s bit unfair to compare the legendary Kubrick whose subtexts are still trying to be deciphered today hahah. The beasts of burden was an easy example which is why I used it (plus I think its a bit early to be looking for those sorts of things right now), but I can see were you are coming from. DU is not my favourite QT movie but I am not let down either, there is the problem of the blending of the surface message and the deeper one, which in this case has been done badly as compared to Inglorious Basterds were there were several clever examples of subtext.

I do agree with you that some of the nods and winks annoyed me, especially with the handshake seen in which the audience saw the gun under the sleeve a mile away and then Schultz as if channeling Tarentino himself remarks, ” I couldn’t resist.” Couldn’t resist going for the cheap trick, perhaps? Although those sort of events are trademark of the spaghetti westerns. It annoyed me nonetheless.

I not too upset as I wasn’t expecting another Pulp Fiction canon movie from QT in DU, but DU hasn’t caused me to lose hope.

Thanks for the reply, heres an interesting read Evil.

http://kottke.org/12/05/the-unified-theory-of-quentin-tarantinos-movie-universe

I’m not sure why comparing Tarantino to Kubrick should be unfair. They’re both just men and only one went in front of an audience to discuss his legacy. But regardless; compare him to a lesser director. Anyone you like. Tarantino’s films are fun but simple on a surface level ( for the most part). There’s a whole layer of subtext that’s like the mumblings of a savant but they don’t connect to the surface in an easily comprehensible way. That’s his hubris. That we should struggle through vague symbolism to find meaning when he can’t be bothered to write a story that encourages that level of engagement. He wants to throw in any odd reference he likes? Ok. I don’t think that makes him impressive. I think it makes him undisciplined.

I apologise for the shortness of this reply but I did write something that addressed the issues you out forth but my device crashed :(

In my opinion, I enjoy when the subtexts are vague. That way I can feel in the blank spaces and see if it connects to what else I know, that way it becomes my own unique experience. Also Kubricks movies are just as mumbling as Tarantino films and this is intentional I believe for the reason above.

When comparing Dr Strangelove and Django its a bit unfair because of the differences genre. DU is primarily a spaghetti western and secondly a blaxsplotation. There’s less room and potential for subtext because of the freedoms and limitation within the space the directors are working.

QT went out to make a spaghetti western in trademark Tarantino style and he has done just that.

Just ti clarify where I am coming from as well, I would put Kubrick’s films over Tarantino’s, but this is unfair because of the fact that Tarantino is far from done.

By the way could you clarify what you meant by first 3 sentences of your last message.

Thanks

no worries Ross. i was writing from my phone so i was a bit terser than normal, too. i will correct that issue now…

you seem to be saying that one can’t compare Strangelove to DU because of genre. that’s reasonable enough. but then you say Tarantino set out to make a ‘spaghetti western’ in his particular style and that kind of blows your first point.

why?

because that’s like saying Kubrick set out to make an anti-war comedy and, achieving that, we need to judge him along that metric solely. i think that’s dubious. Kubrick and Tarantino set out (I hope) to make films of value—entertaining, engaging, provocative films. Kubrick certainly referenced tropes of different genres as did Tarantino (which is why I first thought of Strangelove).

but Strangelove—whether or not you bother to dig for subtext—is a story you’re engaged with and which makes perfect story-sense the entire way through. at the end, even if you just thought you were watching a comedy, you’d be a moron to come away without having the nugget of something more potent implanted in your brain.

in Django, while I can imagine one might dig deep enough to find some sort of subversive or provocative message, i frankly don’t see it or care to see it. i’d put money down that 99% of the people who see it will never see anything more than some hyper-violent revenge fantasy with some odd comedy mixed in and then some hip hop tunes. maybe a few people will think, “gee, slavery was bad, huh?” but… that’s not really the message the surface story even tells.

i’m not sure WHAT message the story tells, frankly. there’s something about being lucky enough to be freed by a bounty hunter, then something about being a naturally excellent shot, and then a bunch of stuff about shooting everyone around you and not getting your nuts clipped. ostensibly, Django just wants his wife back. in the story QT tells, that’s never a problem. Django is rich. Broomhilde is a disobedient slave. Candie would sell her. end of movie.

now people (FILMCRIT HULK for example) would counter that “then there would be no movie, so that’s not a story problem,” but i disagree. in DU, the drama is all fabricated. ridiculous people behaving ridiculously, right? you’ll get tired trying to name all the bizarre actions characters perform in the name of a complex and confusing plot. why is this so? so that QT can develop some murky subtext about horses legs or whatever? if so—then that’s precisely why I don’t like QTs work for the most part. because he doesn’t bother to do his job. he puts on a vaudeville show and tells you that if you watch him torture people and show off there’s a prize inside.

bleh. keep your prize.

there is no less room for subtext in any genre. and if there is, then why would you force yourself into that genre? and why would you make a film about slavery in a spaghetti western style? that’s like making a film noir about the wonders of childbirth. it makes no sense. blaxplotation? sure. that genre could be fun and clever and easily subverted to reflect on a story about slavery.

don’t forget: QT writes his own movies. no one tells him what to do and that is VERY APPARENT. if he’s constrained by anything, it’s himself alone.

subtext is always vague. i’m not saying it should be blatant—then it wouldn’t be subtext. i’m saying it should be accessible. i’m saying someone like me should watch a movie, think about it, discuss it, and have some IDEA of what the hell QT was doing. i don’t. so far i haven’t heard any one else come up with anything either. there’s “he’s citing Roy Rogers with the horse dancing bit” or “this song is a reference to blah blah” but no one has said, “wow. QT really made me think about X.”

he didn’t make me think about anything except why people think he’s so brilliant. and my examples above aren’t even really subtext, they’re just asides or citations or… I don’t even know. easter eggs? in jokes? and whatever they are MOST OF HIS AUDIENCE WILL NEVER GET OR UNDERSTAND MOST OF THEM. so what they really are is masturbation.

in my first three sentences i’m saying: both Kubrick and Tarantino are directors. both have been and are called geniuses. if it isn’t fair to compare them, then maybe one isn’t a genius? (hint hint, it’s QT). one them (hint hint QT) sat at a round table discussion recently to talk about his legacy—as if he was a serious artist worth lauding well past his death. the nerve of that is galling. Scorcese never did something so egotistical. Coppola? Ashby? Wells? no. and then I said if you don’t like my comparison to Kubrick, pick any other director you like to compare him too. I’ll suggest a less universally esteemed one; Don Siegel.

you know that name? great director. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (the original) and Dirty Harry and many more.

what’s Dirty Harry about? is there a subtext there? if you’ve seen it, you know. same with Body Snatchers. because the subtext parallels the story, which makes sense and is entertaining (and violent and popularly engaging).

now compare those films to any QT film you like.

people like QTs style. i have no problem with that. he’s got style. i personally find it irritating.

but i like you and i’m glad you’re interested in discussing this stuff with us.

I think your criticism of Tarantino in general is warranted–his movies are too long, meandering, and far more concerned with snappy dialogue and set pieces than with resolving any larger philosophical or dramatic problem. However, I think you are giving short shrift to Django Unchained, which may well be his best non-Reservoir Dogs movie. Not in your critique of the writing or pacing, but I’d argue that in this film, more than any of his others, he is actually SAYING something.

On the simplest level, the film is an indictment of the institution of slavery. That’s it, it’s not complicated. The fact that Samuel L. Jackson is the last to die is far less relevant than the fact that every other person Django comes into contact with dies in violence. It’s a bloodbath specifically because the entire era and institution was a bloodbath. That’s the point–that an inextricable and historical part of who we are as a society was just massively, unforgivably violent and evil, and there can be no answer to that–just spigots of blood.

Like I said, not complicated, but I think Tarantino is even going a step beyond that here. Because in addition to forcing his viewer to confront this bloodbath, he is attempting to force the viewer to recognize that the myths and stories we like to tell ourselves about our past, especially in movies, have utterly failed to grapple with this reality.

You do properly diagnose Tarantino as a filmmaker–he is much more concerned with movies than with life. But that penchant is used to good artistic effect here. More than anything else, Django Unchained is about old Westerns and old movie heroes from the fictional Old West and Old South. He is saying this: if they weren’t dripping in blood, then they were a lie. If they weren’t forcing you to confront the all-encompassing evil of what our history actually is, then they were a lie. I’d argue that this is both a useful and interesting critique, and that, unlike with some of his films, it is very much at the forefront of what he is trying to accomplish here.

Adam Serwer at Mother Jones explores this argument in detail, and the extent to which the movie is a direct response to specific kind of American Western:

“Django is an inversion of the genre, where the loner seeking revenge is a former slave instead of a former Confederate; where the alien savages who stole his life from him are white, as is the sidekick with the nonexistent past: Tarantino hasn’t simply flipped the notion of a Western hero, he’s even given him an inverted Magical Negro sidekick in the character of King Shultz, a German abolitionist bounty hunter who appears out of the ether to free Django, and dies to facilitate his revenge—much as the death of Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) sets off Clint Eastwood’s character in Unforgiven. Except in Django, deserves has everything to do with it. Django kills white people like he’s trying to make up for a century of on-screen genocide in Western films where black, Latino, and Native American antagonists are treated like disposable pocket litter. The only white man in Tarantino’s Mississippi who survives meeting Django is played by Franco Nero, his Italian namesake.

If the box office take is any indication, Tarantino has not only accomplished all of this genre-busting, but has managed to do it while making white people enjoy watching what is essentially a two-hour-plus lecture on racism in American film, an extended fuck you to DW Griffith and John Ford, John Wayne, and Clint Eastwood.”

Serwer also refutes your critique of Tarantion’s use of violence here, I think pretty effectively. The whole review is worth reading: http://www.motherjones.com/mixed-media/2013/01/tarantino-django-unchained-western-racism-violence

Those are all interesting points. Unfortunately, none of them addresses what to me is the primary issue: DU is a boring mess of a movie. It makes no sense, I don’t care about anyone in it, I almost went to sleep halfway through it. If Tarantino’s purpose was to address the “lie” of old westerns, that’s nice, but I don’t understand how that lets him off the hook for making a bad movie.

The comparison you cite to Unforgiven is completely baffling. Ned dies to “facilitate” Eastwood’s revenge? What revenge? There is no revenge until Ned dies. Eastwood takes revenge on those who killed Ned, and in doing so is forced to accept that he, Eastwood, himself is a monster. That’s what a smart movie does: it gives you the thrill of the killing at the end, while also forcing you to see that the killer is not a good guy, he too is a monster, same as Hackman. The whole movie is a refutation of revenge, for god’s sake. It says that all violence does is create more violence, that no one is Good or Evil.

This is all beside the point. So now DU is a grand statement on the falseness of old westerns? Really? Wow. Another bold move by Tarantino. Let me get this straight: John Ford westerns were dumb, fake cartoons? I’m shocked. How was this not already addressed beginning in the ’60s? Are we supposed to pretend The Wild Bunch didn’t exist? The Wild Bunch is everything DU is not: a hugely entertaining western drenched in blood and violence, that also happens to be saying all old westerns are lies.

The argument is then that Tarantino is saying the horror of slavery may only be addressed by over-the-top cartoonish violence. Well…okay? I don’t personally see how that addresses anything. Tarantino says over and over again in his interviews that like the movie or hate it, it’s started a National Conversation on slavery, one that’s never been had before. This strikes me as ridiculous. Who is saying slavery wasn’t bad? The only conversation is whether making a revenge-fantasy-cartoon about slavery is going to help matters.

And as Mr. Evil Genius points out, 99% of everyone seeing this movie is not having a National Conversation on slavery. They’re getting off on a simplistic, violent revenge picture. Which, I remind you, sucks.

A two hour lecture on racism? Please. “Slavery was bullshit!” There, I just saved you two hours. That’s the entire lecture. Having a slave kick ass is a perfectly good movie subject, but for any intended deeper meaning to have resonance, you’ve got to take the initial step of making a movie that makes sense as a story.

Wait, are you suggesting that you don’t think Django Unchained is a good movie? Are you sure? Noted! This is, however, beside the point.

I’m not arguing that Django Unchained is a dramatically satisfying narrative. Nor am I arguing that the critique that Django Unchained makes is unassailable, or that no one in the history of cinema has offered a similar critique, or offered other critiques more successfully. I’m responding to your claim that, like other Quentin Tarantino movies, Django Unchained has no inherent meaning, and that whatever meanings people may impute to it are not supported by the film itself. I will restate my case: In this particular film, Tarantino does actually mean something, and what he means is indeed supported by the film itself.

Now, whether or not a film can say anything interesting independent of its success in conveying a satisfying narrative or aesthetic experience is a question we can quibble about. Though I must confess, I don’t find it a particularly interesting question. (My short answer would be yes: even bad movies can raise issues that are worth discussing.)

But, I’m not here to convince you that you should “like” Django Unchained. This also doesn’t interest me. What interests me is the question of whether or not Django Unchained has anything to say, and in particular whether it has anything to say about other movies (independent of whether you think what it says is worth saying, which is a separate question). And I would argue that the answer is unequivocally yes.

Let me clarify a couple things and respond to some of the other points you make in your response.

First, “I” am not raising the example of Unforgiven, I was quoting Adam Serwer of Mother Jones. And we can debate some of the specific examples he gives, but I think you may be missing his larger point. Serwer places Unforgiven within the context of “Lost Cause” narratives of the Old West. That is, a kind of story that stems from a particular history of writing about the Civil War that, among other things, elevates the nobility of the Confederacy and their hopeless struggle against the brutality of the North, romanticizes pre-Civil War Southern culture, and generally minimizes slavery as an incidental feature of this culture, if it references it at all.

Now, Serwer is among a school of modern critics (whom I tend to agree with, by the way) who believe that this view of the South and this frame for understanding the Civil War and America’s history of slavery has had an outsized and pernicious influence on stories that get told about the era—and especially the heroic myths that have been told. These critics would argue ,I think, that this propaganda has been perpetuated intentionally at times (DW Griffith), as well as unconsciously (many of the classic Westerns of John Ford and, yes, Clint Eastwood, where the question of race or slavery is barely even hinted at, if it’s referenced at all).

I’m not sure, frankly, that Unforgiven is the best example of the phenomenon Serwer’s talking about. I suspect he is referencing the idea that Eastwood’s character just happens to be best buds with a black guy before and after the Civil War, that no one around seems to feel this fact is worth commenting on really—that whatever else the film may be attempting to express about the grim realities of the American West, this bit of fantasy is ridiculous and onerous. But I don’t know; I don’t want to speak for Serwer.

Frankly, I think a far better example of the Lost Cause and fantasy about the South in cinema, which Django Unchained directly references, is Gone with the Wind. I would argue that the representation of Candie’s sister—and the effortless manner in which she is literally “blown away”—is very much Tarantino expressing how he feels (and how he believes we ought to feel) about this representation of Southern culture, and the romanticized notion of the Southern Belle in American movies.

So this is one specific example. I could dig around and try to provide you with others. But generally, I think this is the critique Tarantino is attempting to make. I think it’s a different critique than the one made in the Wild Bunch (again, independent of the comparative quality of these two movies), which is chiefly concerned with exploding heroic myths about cowboys. Tarantino’s criticism is broader. I would sum it up like this: slavery in this country was so vast and monstrous in its evil that it is not possible to tell any kind of story from that era that does not directly confront this evil. If you are watching any movie about the West or the Old South, and every single person in every single shit-kicker town is not explicitly acknowledging that they are complicit in the violent destruction of human families, then the story you are watching is bullshit.

I would argue that also supporting this, in the film itself, is Tarantino’s depiction of violence, which is more nuanced than you’re giving it credit for. The violence is indeed cartoonish—when it’s directed at the kind of myths and characters that Tarantino sees as basically cartoons themselves. But this is starkly different from how Django Unchained depicts violence against slaves. Scenes of violence against slaves in the film are not reveled in, they are not played for laughs, they are not cartoons. They are brutal and horrific and difficult to watch. For a guy who lovingly photographs bullet-riddled bodies coating a room with blood, I don’t think this contrast is an accident.

OK. So having said all that. You may argue that this critique is made in a ham-fisted manner, or that it’s overly facile, or that it’s a dumb critique to begin with. That’s fine, we can talk about that. But let’s acknowledge that the critique is there, in the actual film, as a starting point.

Well, bravo.

Bully for QT then, he sure showed those mid-20th century Americans what ignorant assholes they were … you know, back when those mid-20th century American assholes were the ones making

“Westerns”.

Which, you might have noticed, was a decent half-century ago.

QT wants credit for ideas that essentially require that the last 50 years of film making don’t exist. [And let’s make no mistake here, “Westerns”, overwhelmingly, aren’t “Southerns” (seriously, Gone with the Wind?), and as such, overwhelming, if there is an unpaid debt that Westerns owe, it remains, not to blacks, but rather to those native Americans that our ancestors sought to poison, cheat, starve and extirpate from the very lands that they possessed. Though, in truth, that is in actual historical reality, there are any number of Westerns that QT could have chose to tell about blacks in the west: black cowboys, homesteaders, ranchers, buffalo soldiers. Hell, he might even have made a black western where buffalo soldiers were forced to carry out orders to drive native Americans off of their land. Gee, imagine the sub-textually ironic field-day he could have had with that!]

Well sure, he might have made a lot of movies on a lot of different topics. But this is the one he made, so this is the one we’re arguing about.

I would dispute your claim that the critique he’s making is restricted to movies from ancient history. I think the Lost Cause narrative, consciously or not, is very much alive in modern movies and TV. (That dumbass FX series about the train comes to mind, most recently.) Most Westerns that tell stories set during and prior to the Civil War, both the stories that get told today as well as the ones from decades ago, have very little to say about slavery, if they discuss it at all. And frankly, I can’t really think of very many movies, in any context, that really try to explore slavery. (I am taking as a given, of course, that nobody in the universe actually watched Amistad.)

There was Roots, obviously, and Glory (which had its own elements of Lost Cause romanticism, even as it tried to tell an enlightened story about race). There was the Skin Game, with James Garner and Louis Gossett, Jr., which I haven’t seen in a million years but I remember really enjoying. But I really can’t think of many modern (or even not that modern) movies that really go there. Maybe I’m missing a bunch, you can tell me if you think I’m wrong.

But in any case, if Tarantino wants to say this is an elephant in the room that movies are shirking a moral responsibility to address, I think that’s a legitimate criticism. Does Clint Eastwood have an obligation to talk about slavery in Unforgiven, or does he just have an obligation to tell a good story? Tarantino seems to be answering this one way, and he may be wrong, but my point is that he is presenting an actual argument about this, not just making a revenge flick with nothing else going on there.

Good points, Jason. And Stu.

Being a bit preoccupied at the moment, I’ll just add this:

Why is QT righting the wrong of slavery’s lack of focus in westerns (specifically Italian-made westerns)? Who is he to address this subject? And did he do so in a way that actually COMMUNICATED that grievance to the majority of his audience? And if he didn’t, what are the most basic messages his film does communicate?

I agree that QT has something to say. I think he’s lousy at saying it. I also think he’s self-aggrandizing and insulting to his peers and predecessors in the way he says it. John Ford and Howard Hawks didn’t address slavery directly? Maybe that’s because they made films in the 40s. I’d be just as reasonable making a film in 40 years about how fucked up QT was to use the word nigger repeatedly in his films today. And scold him for failing to address gay rights and anti-muslim sentiment in his pictures.

Most Westerns that tell stories set during and prior to the Civil War

Well, no.

Not really.

If there’s a six shooter in the story that ISN’T cap and ball, or there’s a Winchester rifle, the movie is not (accurately) set “during and prior to the Civil War”, it’s in the mid 1870’s or later (the famous Colt Peacemaker, aka “the gun that made men equal”, aka THE GUN EVERYBODY IN EVERY GODDAMN WESTERN EVER USES (except, of course, for the “Schofield Kid” from Unforgiven, who of course uses a Smith & Wesson Model 3 “Schofield” revolver) was first produced in 1872).

But that’s kind of an ancillary distraction to the main reality that Westerns just aren’t, as a matter of fact, set “during and [sic] prior to the Civil War”.

Let’s see …

Unforgiven … post CW

Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid … post CW

Silverado … post CW

Pale Rider … post CW

Tombstone/ Wyatt Earp … post CW

Deadwood … post CW

McCabe & Mrs. Miller … post CW

Little Big Man … post CW

The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean … post CW

Appaloosa … post CW

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford … post CW

The Long Riders … post CW

The Wild Bunch … post CW

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid … post CW

Heaven’s Gate … post CW

Of course, I’m missing any number of Westerns, but the reality is, that the vast, overwhelming majority of Westerns made in the last 50 years are (well, actually, ever), historically speaking, are set in time far closer to the dawn of the 20th Century, as they are to the close of the Civil War.

Westerns, as a matter of fact, just aren’t Civil War movies. Even those movies that *are* about Serwer’s mythical “Lost Cause Southerner” (for example the James’ gang or Billy the Kid) for the most part take place in the mid-1870’s or 1880’s.*

It’s just kind of a historical fact, just like 1858 wasn’t “two years before the Civil War”.((Here’s where I’ll also note essentially every gun used in Django Unchained didn’t actually exist in 1858 (or for a decade after), but hey, since Mandingo fighting never existed either, what’s some a little light historical inaccuracy between friends, right?))

Damn your calm reason, sir! I am outraged!

You have made your point. Tarantino had something on his mind in DU, and that something is, in places, supported by his choices in the film.

But the amount of effort expended by you and Serwer to make this point is telling. Serwer bends over backwards in his efforts to commend the movie, and still admits it’s a mess and that half the time it seems like Tarantino has no idea what message he’s sending. You suggest that whether the movie is good, and whether its message has value, and whether the message is presented well, are all beside the point. In the very narrow argument you are making, that’s true. But to my mind, that defeats the whole purpose of talking about a movie. Those side issues are, to me, the interesting parts.

Which interest on my part you also claim to be a side issue. Well, I can’t win here.

As to your point and Serwer’s, I’m not sure what to say but “congratulations.” Yes, Tarantino isn’t a complete moron, I grant you this. He meant to say something in the movie, and parts of the movie even support what he’s saying, however feebly. And it IS feeble. I’m missing, for example, where violence against slaves is not shown as cartoonish. Mandingo fighting? That wasn’t a cartoon?

Also–and it’s after the “also” where to me any discussion of the movie begins to get interesting–Tarantino presents his message in the sloppiest manner possible, to the point where half the time one has to wonder if he even knows what message he’s sending. His message that slavery was REALLY BAD, YOU GUYS, seems to lack a certain amount of depth. His alleged critique of past westerns I think is absurd. As Mr. Pork points out, if we’re going to slam Ford westerns–which we might as well, I kind of hate them–we should slam them for their depiction of Native Americans.

But okay, the claim is that Tarantino is critiquing ALL past westerns that don’t deal directly with slavery. You agree with this claim. I think it’s outrageous. Are we really going to limit what stories artists are allowed to tell? The school of criticism that criticizes art for what it doesn’t include drives me insane. Now all westerns must deal with slavery, or they’re pernicious and harmful to society? What if someone wants to tell a story about a person living in that era where the focus isn’t slavery? Are they out of luck? Did the oversights of past filmmakers doom today’s artists, forcing them to right those past wrongs?

Serwerd’s example of Unforgiven is the worst one possible. I realize the movie is the movie, but by the way, if you’re curious, the part of Ned wasn’t written as black. Eastwood likes Freeman and wanted to cast him, so he did. That’s why no one mentions his race. The movie isn’t about racism or slavery. It’s about violence, and is itself a damning critique of how violence is portrayed in westerns. Isn’t that enough? Or must we consider it a failure for not also addressing the horror of slavery? Is that what Tarantino is arguing? If it is, I think it is at best an asinine argument, and at worst the beginning of censorship.

If Tarantino thinks that movies set in that era have failed to adequately address slavery, and that he’s going to remedy this oversight by making DU, that’s great. Good for him. But to then argue that everyone else who’s ever made a western is guilty of shoving slavery under the rug is ridiculous and insulting. And if he’s ONLY talking about Ford westerns or others from that era, then again, we’re left to scratch our heads and say, “No shit.” Those movies were not made in an era where this kind of commentary would have been even remotely considered by anyone, anywhere. You couldn’t have black singers on the radio! And now Ford is guilty of not curing the country’s racial woes?

Which I know, this is all beside the point in what you’ve argued. But where does your argument get us? There’s nothing left to say. Yes, Tarantino meant to say something with his movie. And…?

And that’s when any valuable discussion of his work begins. Is his message effective? Is it meaningful? Is it presented artfully? Does it mesh with other issues in filmmaking such as storytelling, editing, pacing? How does it compare with other films with issues on their minds? Does it show a genius at work, as many people argue, or does it show nothing but a flashy showman?

Which I realize you’re not saying we shouldn’t discuss all of that. You were only arguing that I said there was no meaning in Tarantino’s cartoon, when in fact you argue there is. But dang it, ya gots me all het up!

Oh, I will respond to this, Being, (that’s right, I called you “being”), have no doubt about that. But I think my wife is getting irritated with me sitting here typing all day, so it will have to wait till tomorrow. Briefly though, I am not suggesting that you’re not allowed to talk about any of the things you want to talk about. (I conceded the point on whether DU represents a satisfying narrative–it doesn’t–and on Tarantino’s problems as a storyteller in general. I think your arguments on this are well said.)

I do disagree that a failure to tell a story well obliterates anything else a film might be doing. (And I suspect you are convinceable on this point, at least in the context of bad films that were nevertheless “important,” of which DU may be one.) But that also we can argue about if you want to.

My point was just let’s agree that, in this particular case, the man does genuinely have something to say, and THEN we can begin properly arguing about what he’s saying and whether or not it’s dumb. (Which I look forward to doing.)

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to go interact with my family before they start kicking me.

OK, so I’m back. Hopefully you’ve all had a relaxing Saturday and plenty of time to sharpen your knives!

Sean, apologies if I was unclear. I do not necessarily agree with the critique (or the way you’re articulating the critique) that any Western that doesn’t directly confront slavery is a bad movie. What I meant was, I agree with Adam Serwer, and with the larger group of critics and historians who believe that Lost Cause mythology has had an outsized influence on American mythmaking in film and fiction as part of a larger, originally conscious effort to obscure and rewrite American history to minimize the stain of slavery.

I think they would argue (and I would agree) that Lost Cause propaganda has become so ingrained in our cultural history and storytelling that we are often not even aware of its influence. In general, any movie (and any Western) where you have a hero (or antihero) who is a former Confederate soldier, who lost his home/ranch/wife/children in the war, who is out West because his past (prior to or during the Civil War) has been erased, all these kinds of characters flow out of Lost Cause mythologizing about what the South lost during the war. Again, I think a lot of times people don’t even think about where these stories come from or their implication. Firefly, which I love and which is created by about as big of a fluffy multi-culty liberal as you will find in Joss Whedon, is, nevertheless, the Lost Cause myth as space opera.

So anyway, I would argue that this trend exists, and that it exists in a lot of Westerns. (And Stu, I would argue that it exists in many Westerns even outside of any direct reference to the Civil War, in the form of lone heroes out West piecing their lives together after the Confederacy.)

So this is all kind of discursive, sorry, I am still drinking coffee. I guess I’d narrow down to two questions: 1. Is Tarantino’s critique of other films fair or otherwise worth considering? And 2, to both Sean and Zack’s point, does this critique come through in the film in a way that viewers will actually think about it?

For the first question, is this fair, I am going to cop out and say “I’m not sure.” I love Unforgiven. I love Sergio Leone Westerns (and Tarantino does as well, obviously). I even like plenty of John Ford movies. (Fort Apache features one of the best villains Henry Fonda ever played.) So from the perspective of a guy who likes movies and good storytelling, I am temperamentally inclined to agree with Sean—my first concern when I go to a movie is, is it a good and well-told story? As an artist, I would agree this probably should be your chief concern. But this is the question I think Django Unchained raises, which I find interesting: Are there evils that are so vast in their depth and scale that stories that touch on that evil, even peripherally, have a moral obligation to address it?

So to further my cop-out, I think Tarantino is saying with this movie that yes, they do. That if they don’t, they are morally culpable in some way—they have been co-opted by those who wish to hide and rewrite the history of that evil. I don’t know if I entirely buy that, but I think it’s a really interesting and worth-while question to ask.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is a great, great movie, one of my favorites of all time. It is also, I think a prime example of the critique Tarantino is making—a film that is inextricable from its context in the Civil War era, that plays on many Lost Cause myths about the Confederacy and the Union—and that manages to almost totally avoid dealing with slavery at all. So then, does this constitute a moral failing of this movie? I just think it’s a great movie. But I think this critique is a legitimate one, and I could be persuaded by it.

So second question, does this critique come through in Django Unchained, or will people just see it because it’s a revenge flick bloodbath? Well, it IS a revenge flick bloodbath, and no doubt that’s what fills the seats. But I think it DOES come through in the film, without requiring all that much thought or digging on the part of anybody who has seen a lot of movies. (Tarantino is not exactly a subtle dude.)

And even among people who will not get any direct references to Gone with the Wind or Sergio Leone Westerns, I think the depth and scale of the evil of slavery absolutely DOES come through. I would argue that’s the one thing this movie does very, very well, and the reason why it is important. (Sean, I know you find this to be completely obvious; I’d say again, for something that ought to be completely obvious, it is shocking how few movies and stories in modern culture touch on it at all.) So just for depicting slavery, for showing one fictionalized and sexed-up account of what it meant to individual human beings and families, I think the film is doing something important.

I think you guys probably spend less time than I do on the internet arguing with morons (he said with no trace of irony or self-awareness). But there are still a LOT of people who buy into Lost Cause mythology wholesale. Anybody who calls the Civil War “the War Between the States” is doing this. Literally last week, some jerkoff on a message board was posting a bunch of links trying to convince me that slavery wasn’t as bad as it’s made out to be today—that slaves were actually treated pretty well by and large, that the South had legitimate grievances and was right to secede, that the idea that the Civil War was really about slavery is just revisionist history.

So this guy was an idiot. But there are LOTS of people like him to a greater or lesser extent, and who at least buy into parts of this mythology, just because it’s so pervasive. So to the extent that Django Unchained forces people who watch it to say, “Wow, no, you actually can’t even exaggerate just how supremely fucked up and evil this was,” I think that’s a positive thing. To the extent that the success of Django Unchained spawns a series of new movies about slavery, causes Hollywood to really confront the subject in a way that it hasn’t before and try to tell some more interesting stories about it, I think this is also a positive thing.

So there you go, another novel. I’m sure I didn’t address all of your criticisms of my argument, feel free to throw ‘em at me.

I feel like this is one of those discussions where we’re only disagreeing about the importance of points, not the validity of points.

I don’t think anything you’ve said is incorrect, I just think you’ve over or under exaggerated the relevance of what you’ve said.

is/was the Civil War about slavery? sure. to some degree. in the same way that the Gulf War was about oil. but if you make a film like, say The Hurt Locker, are you obligated to discuss OPEC, or Dont Ask Dont Tell? if you were a solider in the Civil War what percentage likelihood would there be that you’d been a slave owner? do you see what I’m getting at? sure; there might be a subtext about slavery in some Lost Cause westerns. and I even think perhaps, if cultural growth were otherwise, there might have been. but it wasn’t and there weren’t.

Josie Wales didn’t have slaves. Josie Wales wouldn’t have had slaves. He became a Confederate Soldier because the Redlegs murdered his family. In that story, should there have been some discussion of the grand political motivations of the Union/Southern forces? I say no. It’s a myth.

And you (and QT) say “it’s a myth founded on lies.” And I respond, “no shit. it’s a myth.” And then you say all the well considered things you said above and I shrug and say, “QT’s importance and relevance is also a myth founded on lies.”

I did not come away from Django Unchained thinking, “damn slavery sure was a travesty.” I came away thinking, “What the fuck was that idiotic scene with proto-klansmen arguing about hoods? Why was house slave Stephen portrayed as worse than Candie? What happened to all the other slaves in all the other plantations that Django rode through? What happened to Big Daddy’s slaves after Django killed his men and earned his money? What, if you think about it, is there to like about Django as a man? He’s vicious and violent and unthinking. He killed those Australians who were just as willing to help him as enslave him.

were we wrong to glorify some Confederate soldiers in western films? maybe. but… that horse has left the barn.

and i guess i feel DU is essentially QT saying, “shame on all of you. I’m the one who sees the pain and suffering of the world.” and really? people in glass houses etc etc

i have more to say but i need to go buy a house now.

So I have not dropped off the face of the Earth, just got busy with snow days and work and such, but I do want to continue this conversation, because I think it’s an interesting one. I had composed most of a response to Zack a couple days ago, and then Sean screwed everything up by posting his own response and raising a bunch of points that I don’t have time to respond to at the moment, though they are certainly worth discussing. But it will have to wait; in the meantime, this was my response to Zack:

I would disagree that the Civil War was about slavery in the same way that the Gulf War was about oil. This is a much larger conversation, and since neither of us are Civil War experts, we would probably be better served to hire two people who know what they’re talking about to have this debate and let us listen to it. But absent that, I would recommend the series of posts by Atlantic blogger Ta-Nehisi Coates called “The Civil War Isn’t Tragic” and the longer article that resulted from them, to give you a sense of where I’m coming from in my view of the legacy of the Civil War, and the battle over how that legacy is portrayed: http://www.theatlantic.com/personal/archive/2011/12/the-civil-war-isnt-tragic-the-source/249745/

But for the purposes of the discussion at hand, I think the difference here—which I would argue is central to the critique Django Unchained is making—is just the sheer scale of the monstrousness we’re talking about (or not talking about, as the case may be).

I’m going to break a cardinal rule of the internet, but I think it’s time to start comparing things to Nazis. First because I think the Holocaust is the only thing in modern history that conveys the same scale of evil as slavery in the United States, and second because, frankly, there are a lot of parallels. So when I hear you say things like the Civil War was about slavery to some degree, that’s the parallel that leaps to mind: There are a million stories we could tell about Nazi soldiers. Do ALL of them have to talk about the Holocaust???

I realize this sounds like a straw man argument, but I think it’s an instructive one, and I’m going to torture the analogy a bit further. Imagine if, in the wake of the Holocaust, we had decades of stories and movies coming out of Germany about the period. But rather than referring to the mass murder of millions of people, virtually all of those stories were about ubermensches and romantic tales of heroic Nazis (or gritty but determined Nazis) and the lives they led after their families and homes were ripped away from them because they tragically fought on the wrong side in World War II. Now, maybe some stories along these lines would be great stories. But if ALL the stories from Germany about WWII were along these lines, and virtually NONE of them even acknowledged that whole mass murder of millions of people thing, I suspect we would be rather… disturbed.

Now, I think in the Germany of the real world, you probably could tell other stories about the period without having a moral burden to explicitly talk about the Holocaust, because as a culture, Germany has confronted the depth of evil that it was responsible for, for many years and in many ways. And certainly, to a depth that I think American popular culture never really has in our myths about our past—in large part because of the concerted efforts of Confederacy apologists who began spinning Lost Cause mythology literally within days of the end of the war.

Before you think I’m just wallowing in white guilt, let me be clear. I don’t think we have an obligation to talk about slavery in every movie that gets made, or that any movie touching on the Confederacy is implicitly a “bad movie” if it doesn’t directly address it. But I do think it’s valid to look at the stories we tell about our history and point out where they derive from a mythology that obscures a vast and profound evil, rather than confronts it. And to suggest, hey, maybe we ought to. Especially when there are so few stories about our past in pop culture that acknowledge it at all.

I can’t help thinking again about Unforgiven, and Clint Eastwood casting Morgan Freeman as Ned Logan even though the part wasn’t written for a black actor (which I did know). To me, this fact is a perfect example of what we’re talking about. Clint Eastwood, who I believe is a very smart and enlightened dude, is so confident in how far we’ve come as a society that he can just cast a black actor for this part, and nobody says much of anything about it. Except in any realistic depiction of the times, somebody WOULD say something about it, it would be a huge deal. The notion that there is some version of our past where it isn’t is the fiction Unforgiven is peddling, intentionally or not.

So back to Django Unchained. I think you can make a case that whatever critique Tarantino is making, it is muddled and contradictory and self-congratulatory. Because clearly, Westerns are among Tarantino’s favorite movies and biggest influences, and his portrayal romanticizes these stories even as it attempts to turn them on their head. But I don’t take his critique as attempting to be the final answer on this topic or a corrective that rights all past wrongs. I think it boils down to yelling, “Hey! This is important! We should be talking about this more! And we should be talking about its absence in our myth-making and asking why that’s the case.”

Fair enough, Jason. I see your point and even agree with you to a certain degree. But I still think we’re arguing about irrelevancies. Why? Because DU doesn’t in any way correct the perceived or actual wrong committed by films that subsequent commentators have dubbed “Lost Cause” westerns. (and while I accept there were so-called ‘lost cause’ mythmakers, I don’t believe John Ford, Howard Hawks, Sergio Leone, and Clint Eastwood were among them.)

QT set out to do something that you convincingly argue has a valid basis. He made a film that you are able to see meaning in; ergo that meaning exists. As a result…

Nothing.

We aren’t having a discussion here about how fucked up slavery was (it was fucked up. no one disagrees.) We are having an argument about the merits of QTs work—which is what QT is really concerned with; himself, not slavery.

At the best, you could say, DU is an indictment of the Western genre for failing to address slavery. But that’s such a wonky, debatable, nit-picky point that who really cares if it’s right or not? You make an analogy to Nazi’s and WWII. Good. Was Schindler’s List or the Pianist an indictment of the Dirty Dozen or Das Boot or Catch-22 for leaving out the holocaust? No. Why? Because doing that WOULD BE A WASTE OF TIME and INEFFECTIVE. During the War itself, I’m not aware of films made that addressed the Holocaust. Later, sure. Just as now there are films about slavery—just not Westerns (except, perhaps, The Searchers in an oblique way? Or perhaps you want to call Glory a semi-western for its period setting? Anyway.)

You and QT suggest that the complete failure to address slavery in westerns is a travesty that requires amendment. You suggest westerns elevate the Rebs and forgive by omission the crime of slavery. I think that’s a simplistic way to look at it. And even if it isn’t—a Civil War Western that addressed slavery would never have been made at any time at which it could have made any difference to actual slaves. Today, no one makes Civil War westerns about slavery for the same reason that no one makes romances about clams; the styles/themes just don’t really blend well (as I think DU proves). (And because as pleasant as it is to see an ex-slave like Django get some of his own back, what he does in DU is TOTALLY AND COMPLETELY UNBELIEVABLE IN EVERY WAY. If QT wanted to address the horrors of a real event, he might have tried having something even remotely real in his film. But he doesn’t—it’s a bizarre fantasy; because he’s not addressing the horrors of slavery, he’s addressing the horrors of NO SLAVERY in old movies. You will excuse me for not being impressed by this.)

Westerns are set in the Civil War not because that war was/or wasn’t about slavery but because that was the war that was occurring in that historical period of America in which the Western myth lives. The Mexican Revolution also features in westerns for the same reason—and I guarantee you that people who made those films were as concerned about the freedom of Mexicans as they were about slaves; i.e. not at all. The Western is a mythical genre for the most part. So if QT is complaining it failed to address reality, I hear that. I’m not sure anyone over the age of 12 thinks there really were cowboys and such like in Westerns. American myths don’t bring up our terrible flaws? Hm. I’m shocked. Shocked I say!

And if DU is an indictment of the unreality of the western myth, I have no idea why DU commits the same crime. Mandigo fighters? Candie Land? Funny clansmen? That’s his indictment of unreality in movies… ? You could say he’s being meta but I say he’s being unproductively obtuse.

As dull as I understand Lincoln to be, I bet an incalculably larger percentage of viewers left that film thinking about the horrors of slavery than those that left DU. Because DU does not address the horrors of slavery any more than the Dirty Dozen addresses the evils of fascism—regardless of QTs intentions or meaning.

And that’s why whatever it says or wants to say or wherever QT is coming from is pointless. Because he failed to communicate.

Just one brief thought for you, Jason, regarding Unforgiven: Freeman’s character isn’t black. I don’t only mean it was written as a white man, I mean the casting of Freeman didn’t turn Ned black. The times depicted are still perfectly realistic because Freeman is playing a white man. You can tell this is so by the way the other characters relate to him.

Well, dadgummit, that’s a lot to respond to. Let’s see what I can come up with.

Is Tarantino’s critique fair? I don’t know. Maybe? The problem is that I still don’t know what he’s critiquing. All westerns that don’t deal with slavery? All westerns of what you call the Lost Cause myth? And where is this critique again? You say it’s obvious in the movie. I don’t agree. I see where you and Serwer are pointing out certain elements, and sure, I can see how you’re able to build an argument around them, but I still stand by what I wrote in my article: it think people looking for meaning are finding it.

I happen to think that an artist’s intent is reasonably irrelevent in discussing a movie: it’s what’s in the movie that matters. But I’m curious: does Tarantino talk about this at all? I’ve seen some interviews, and all I’m hearing is how the movie is meant to show the true brutality of slavery. Of course he constantly references spaghetti westerns with the editing and types of shots, but are you sure that’s not just because he likes those movies? You’re sure his putting that stuff in there is a critique of those movies? Seems like a sketchy argument to me.

With the horse dancing moment and so on, maybe he’s saying that black characters can be heroes too. By saying that, is he necessarily critiquing those older movies? Or is he simply adding something to the movie canon that addresses issues not normally addressed?

I think you can safely remain a fan of The Good The Bad And The Ugly. I’m not sure we can blame an Italian for not dealing with American slavery in his westerns. Now you might say that Leone was of course influenced by American westerns, and that American westerns arose in the way they did owing to innate racism in our society. That may be so. But do we blame Leone for that? I don’t think so. I think it’s hard to blame any artist for the times they grew up in. It can be awfully hard to see what’s wrong around you compared to what can be seen in hindsight.

I’m likely too cavalier when I say it’s obvious that slavery was a grand evil. There are, as you say, a lot of idiots out there. And it’s true that slavery is not often dealt with in movies. You certainly don’t see slaves as heroes ever. But while Tarantino does right that wrong in a sense–he offers a kind of heroic slave–I’m not so sure he’s done such a great job showing the evils of slavery.

I still contend that this movie is a cartoon. I don’t see the way slaves are treated in it as being any more realistic than the rest of the movie. The whole movie hinges on a fantasy: Mandingo fighting, which not surprisingly Tarantino took from another movie.

I think what Tarantino has succeeded in is making a violent western where a slave gets to be there hero. I don’t think it’s a good one, but others disagree. So okay, good for him. But does it teach us anything, really, about slavery? Are those idiots you mention scratching their moonshine encrusted beards and thinking, “well heck, I guess slavery was pretty rough after all”? I doubt it.

And is the average movie-goer going to be at all aware of some deeper critique of all past westerns? No way. This point is slightly belied by the fact that we’re talking about it, but I don’t think we’re average movie-goers. The fans on other movie nerd sites seem to really think the movie is meaningful, but have quite a bit of trouble articulating what that meaning is. Serwerd does a lot of heavy lifting on their behalf, but I don’t think he pulls off what he thinks he does. I think you guys are really reaching, you’re really working to find any kind of consistent, artfully rendered meaning in this movie. To say that some shreds of meaning do exist, ergo the movie has value for offering those shreds, doesn’t cut it.

The movie has value for giving us (or at least those who actually like this turkey) a black, ex-slave hero in a context not seen before. I’m not seeing much else.

This thread is clearly not long enough, so I will add a few cents. There’s the thing, forget about how this fits into the history of Westerns. QT is clearly not that great on actual history and making actual points. He makes entertaining films with a lot of in jokes about b-movies in them. I was happy to find that I genuinely enjoyed this movie. I haven’t enjoyed a QT movie since maybe Jackie Brown. He’s sloppy at structure and has no sense of pace, and jesus, he should never, ever cast himself in his movies. He’s a terrible actor, and it stopped being funny a long time ago. Actually, there was a lot that I enjoyed about Inglorious Basterds, mostly having to do with Christoph Waltz’s performance, but it made me angry, because I know there’s a great movie to me made from that idea. I was so pissed off when the film jumps to a point where the crew is already famous for having thwarted the Nazis dozens of times, and then it takes three hours to perform one stupid caper, which, yes, someone was going to do anyway. How about showing me all those crazy capers? Now, that’s a fun movie.

But anyway, what jumps out as me in this thread is the rather flippant assertion, (to paraphrase) “wow, slavery is bad. Who would argue that? We haven’t learned anything here.” So the idea that we’re supposed to learn something in a QT film is pretty silly, anyway, but answer this, how many films have been made in the last, say, 20 years that had anything to do with slavery? How about films that people actually wanted to go see? How about films that young people might go see again and again? There aren’t any. Obviously nobody thinks slavery is a good thing, but do people, especially young people have any sense of what it really was? Many of us get our sense of history from watching movies. When I was a kid, everybody saw Roots on TV, and it’s from that that I have any sort of feeling about what slavery was and how it was practiced. I still remember some of the scenes of whipping and torture, and it really made an impact. I don’t think I would assert that QT made this movie to teach anybody anything, but I do think it’s great that this movie is really popular, and there are a lot of people going to see it again and again. Yes, there’s a lot of ridiculous, made-up stuff in the film, and it varies drastically in its tone, but the scenes of slavery I think were handled very carefully, and I felt like we should be seeing this sort of thing in America as a reminder. Especially in a time when they are rewriting history books in the South to minimize the importance of slavery in the Civil War. I guarantee you there are at least a few kids in the South and elsewhere that have never seen a character they care about in that situation, and they might feel differently about slavery in general, or at least have a more visceral sense of it.

One other thing, it makes me smile to see you steam, Sean, over a scene in the movie that doesn’t forward the plot, with the Klan members and the eye holes. That rule about always forwarding the plot is a good one, I think because when we see a scene like that, as an audience we feel like our time is being wasted. So this scene here does not, indeed, move anything forward, but it is really fucking funny. If I’m laughing, I don’t feel like my time is being wasted. Jesus, can we not take one little detour if it’s actually funny? I was fine with it.

So it was not a great piece of art, but I found it to be a lot of fun, and the icing on the cake is that some people will be reminded of the horrors of slavery, which is a subject absolutely no one is making movies about. Lincoln, you say? Wait, was there slavery in Lincoln? There was barely even a Civil War in that movie. I did actually like Lincoln, but it was entirely about some white men trying to pass a law. So if you’re looking for something redeeming in a QT movie, well, you’re just being silly, but also, there is that in there.

I think I made my point about slavery as simply as I could in the reply above yours. Yes, it is true that slavery is not seen in movies often, and slaves are never the heroes. So that’s something. But I don’t see much careful representation of slavery in this movie, and I have a hard time thinking that anyone’s going to come out of it saying, ‘wow, slavery really WAS bad, I had no idea.’ It’s mostly presented in the same cartoony way as the rest of the movie.

Speaking of the Klan scene, how is that going to shed light on the reality of slavery? It’s well and good for as us to mock the dopey klansmen, but you can bet there weren’t many slaves who found them funny.

We’ve had this discussion about ‘rules’ before. I don’t have rules. Movies don’t have to follow them. But when movies fail to work, it interests me why, and to express those reasons, it can sound like one is stating ‘rules’ being broken. Of course any rule you can imagine has been broken successfully at one time or another.