To dream of the devil and wake in a fright.

-Old English curse

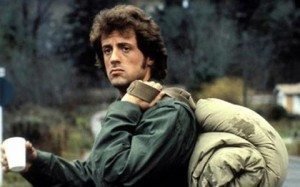

Supreme Being and I went to catch Ted Kotcheff‘s recently rereleased 1970 film Wake in Fright last night. When we sat down in the theater, I mentioned to SB that Kotcheff also directed 1982’s First Blood. And with that in mind, we settled in for just under two-hours of watching a school teacher become increasingly unhinged in outback Australia.

As a bloke what’s lived in Australia for a bit, I recognized places, people, and situations—particularly at the beginning and end of the film—as real. So I empathized with the bonded schoolteacher played by Gary Bond, who gambles his short term solvency to win his long term freedom, and loses. I recognized that bar, busy with endlessly filled schooners of ale; a highway decorated with desiccated kangaroo corpses; people tossing tinnies of beer to whomever appears; the guy next to you at the bar, just extending a hand and assuming you’re mates.

Familiarity doesn’t help Gary, though. He gets mired in a middle-of-nowhere city when he’s trying to escape to Sydney and on to England. In “the Yabba,” Gary gets sucked into alcoholism, violence, filth, immorality, and despair. He’s a pretty-boy and he’s superior, but that doesn’t protect him from his inner wildness, as personified by an excellent Donald Pleasence.

And that’s what I thought was most interesting about Wake in Fright and First Blood (which is really quite good, particularly if you’ve only seen Rambo, which isn’t at all).

And that’s what I thought was most interesting about Wake in Fright and First Blood (which is really quite good, particularly if you’ve only seen Rambo, which isn’t at all).

When I studied Westerns way back in college, “Man vs. Nature” was identified as one of the great themes of the genre. But in those films, the wilderness is outside—it is rough terrain, fierce creatures (man and beast), and the elements. Can John Wayne protect the settlers from Native Americans? Will the homesteaders survive on the edges of civilization?

In Wake in Fright and in First Blood, the wildness is in us. No matter how we dress it up, the animal lives within, ready to smear its hands in blood. Willing and anxious to, actually.

In Wake in Fright and in First Blood, the wildness is in us. No matter how we dress it up, the animal lives within, ready to smear its hands in blood. Willing and anxious to, actually.

Society—interpreted by Kotcheff—is a poorly made blind. Watching his films, we can recognize the struggle within ourselves as we constantly tamp down our nature. The experience is ugly, but not dull. His message is a rough slap, but he also offers us pity. He’s sorry for Gary Bond, and for John Rambo, and for you, too. Because he knows no matter how nicely you’ve tied your tie, or how politely you’ve responded to the sheriff, all it takes is a tiny push. And then the gun is in your hand, the knife is in your grip, and you’re howling.

Kotcheff also knows how to build visceral, lasting images. Despite his unattractive subject matter, there’s a lot going on in these films visually. Whether you’re able to see the beauty in laughing, sweaty faces, sloshing beer, and endless miles of outback is your challenge.

And I will politely not mention that Kotcheff also directed Weekend at Bernies.