Wind blows dust and leaves through a small Texas town. Everything is fading, everything is dying. Cracked, dirty windows obscure the view. The pool hall is empty, its screen door banging in the wind. A kid with a broom sweeps the street all day long. It never gets any cleaner. No one goes to the picture show anymore. The theater marquee is blank, the hope for the future seen in its last presentation, Red River, existing only in the movies. Sam The Lion remembers a girl from twenty years ago. She was wild then. She was married and miserable and young and wild. Now she’s still married, and still miserable. And Ruth Popper, she too is married and miserable. She hasn’t left her husband because she was raised not to. Sonny comes into her life and suddenly her world is full of colors. They don’t last either. The town of Anarene is blowing away.

Peter Bogdanovich shot The Last Picture Show (’71) in black & white because Orson Welles told him to. Smart guy, that Orson. Black & white movies are imbued with age no matter when they were made. They too are suggestive of a fading past. Bogdanovich, a film historian before he ventured into directing, is in love with old movies, with eras disappeared, with the notion of time swallowing up everything and leaving only dust behind. All of which he brings to The Last Picture Show. It’s his second feature, following his debut, Targets (’68), made on the cheap for Roger Corman, whose requirements, aside from the low budget, were that Bogdanovich use Boris Karloff (who still owed Corman two days of work), and parts of Corman’s own film The Terror. Samuel Fuller helped Bogdanovich with the screenplay. Targets wasn’t a hit, but it made an impression, and gave Bogdanovich his start.

The Last Picture Show is based on the novel by Larry McMurtry, his third. McMurtry collaborated with Bogdanovich on the screenplay, but didn’t enjoy it. He’d already written the story once. Having read the book, I think this is one of those rare instances where the movie is better. It’s better because the strength of the performances allows what in the book are pages of inner dialogues to be shown through nothing more than a look in someone’s eyes, how they carry themselves, the way they’re framed in a shot. The movie does what cinema does best: it shows us the inner lives of people without words getting in the way.

The final scene may be the best example of all (don’t fear, this won’t spoil anything). It’s the emotional core of the movie. Sonny (Timothy Bottoms) returns to the older woman with whom he had an affair, Ruth (the incomparably brilliant Cloris Leachman, about whom more in a moment). In the book there are pages spent describing the swirl of emotion going through her head, every angry thought she’s had in the last three months, every depressing vision of her waning life, every thwarted hope for a future that can’t be, everything the affair and its end mean for her, and why they mean what they do. In the movie she has one emotionally explosive speech, not a long one. Sonny says not a word. As she holds his hand she tries to say more, but can’t get out the words. In her face we see those pages of writing. It’s all there, her entire journey. From a place of mad havoc to a kind of inner peace. She says her last line, the same as in the book, and it’s among the most powerful moments I’ve ever seen in a movie.

The story focuses on one year in the life of Anarane, Texas, ’51 to ‘52. The teenagers are Sonny and Duane (Jeff Bridges), football players who, the old-timers remind them in a running joke, never learned to tackle, and Jacy (Cybill Shepard), the pretty rich girl who plays with men until she’s bored, leaving wrecks in her wake. Bogdanovich discovered Shepard on the cover of a magazine. It’s one of the those great examples of a filmmaker using someone who’s not an actor in a way that relies more on who they are than what they’re able to play. Famously, Bogdanovich began an affair with Shepard during the production, which essentially killed his marriage, though his wife, production designer Polly Platt, says she put all her personal issues aside and finished the movie anyway. Bogdanovich continued to use Shepard in movies to worse and worse effect, refusing to listen to those (i.e. everyone) who told him she couldn’t act and was sinking his career. Not until his career was sunk did he seem to realize what he’d done. After The Last Picture Show he made a couple more somewhat successful pictures, followed by a series of terrible ones, all of which bombed. He never made another movie as good as The Last Picture Show.

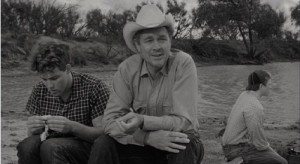

Among the older townspeople is Sam The Lion, played by Ben Johnson, a veteran of westerns. He didn’t want to do to the movie. Too much dialogue, he said. Bogdanovich got John Ford to call him and convince him. Johnson anchors the movie, same as he anchors the town of Anarane.

The other best scene of the movie is all his, when he takes Sonny and his own son Billy (Sam Bottoms) to an old watering hole, and talks about the wild woman he knew in his youth. Bogdanovich shoots the scene like he does the rest of the movie: subtly and with care, giving great power to the simplest of camera moves. Sam sits on a log. As Sonny sits beside him the camera pushes in slightly. Sam begins his speech. As the sun breaks through the clouds (nice work, sun), the camera begins pushing in slowly, until only Sam is in the frame. He continues, and we pull back. Finally, a last pull-back to where we began, as the scene fades out. Too many directors use tight close-ups and endless, rapid cutting to shoot emotionally powerful scenes. When done purposefully, simple camera movements are far more meaningful and emotional.

Sonny and Duane decide on a whim one night to drive to Mexico. Sam sees them in their truck as they’re about to leave. He says if he were younger, he’d go with them. He takes a long moment, then. Sam’s thinking hard about coming along, but knows he can’t. His wild years are over. He stands back watching the truck drive away.

A lot is said in The Last Picture Show with nothing more than a look. In a later scene (which, okay, is another best scene in the movie), when Jacy’s mom Lois (Ellen Burstyn) drives Sonny home, they too have an unspoken moment after each tells the other they can see what Sam saw in them. There’s a pause where she considers Sonny with a little smile, then says, “Nope, I’m just gonna go on home.” In her younger days, she would have jumped him.

Sex plays a big part in The Last Picture Show. Every sex scene manages to be in one way or another uncomfortable, sad, brief, scary—in every case, far from romantic. There’s poor Billy, who never talks, just sweeps the road all day long. The other kids decide to get him laid, take him to an obese whore in the backseat of a car. It’s not pretty. Sonny and Ruth’s first sexual encounter is preceded by their first kiss, outside, standing over a garbage can. When they make love, she clings to him, turns her face away and cries. The bed squeaks and through her tears we see a woman for whom nothing has ever gone right. There’s a rich boy who won’t sleep with Jacy if she’s a virgin. She decides to let Duane go all the way with her, then lies on the motel bed insulting him, demanding that he “just stick it in!”, the poor guy. The hottest sex scene is also the most disturbing. Jacy lures her mom’s older lover to the empty pool hall, where he takes her on top of the pool table. Two shots in the scene are close-ups of Jacy’s hands reaching through the netting of the table’s pockets, and holding on tight.

One of my favorite performances by any actor in anything is Cloris Leachman as Ruth. She portrays a whole life without having to say a word (not that she doesn’t have lines, it’s that all you need to know is in her eyes). Bogdanovich refused to let her rehearse the crucial final scene in front of him, said he wanted to see it the day they shot it and not before. She did the scene once. He said “Cut it and print it.” He wouldn’t let her do another take. Now that’s a ballsy move for a director.

There’s not a bad performance in here. Randy Quaid shows up as a dorky rich kid, Eileen Brennan is wonderful as the tired café waitress, and Clu Gulager (who I will always have a soft spot for based on his role in The Return of The Living Dead) nails the creepy Abilene, a man of few words and many lovers. More impressive still is that none of the actors was a star at the time. Shepard and Bridges and Quaid had never been in anything. Many of the others were just starting out, or like Leachman was really only known for television work. Leachman and Johnson won Oscars for their performances. Bridges and Burstyn were nominated.

The movie is shot by Robert Surtees, who got his start in ’43. He turns the town into its own character. The wind always blowing. The streets empty. Wide, cold panoramas, dark interiors. Every scene is full of life, even if that life is drifting away with the leaves. There’s no music score, only source music coming from radios and record players, of songs popular at the time, mostly by Hank Williams Sr. (“Blue Velvet” also plays, making me think of Lynch’s Blue Velvet, which makes me think of the lone traffic signal hanging on a cable over the road in Twin Peaks. There’s the same lone signal in The Last Picture Show.)

The Last Picture Show isn’t exactly depressing, despite the seeming bleakness. It’s a coming of age story intertwined with the story of an age coming to an end. And it suggests that this is the way of every age, that it’s happening now, and will forever continue to happen. What happens to these kids shouldn’t be read as bad or awful or miserable; what happens to them happens to every kid. Youth isn’t romantic to those living it, it’s romantic to those remembering it. The past is romantic, and it’s forever vanishing. It’s as though the characters are nostalgic for the present.

Late in the movie, Sonny and the other kids, newly graduated, driving to some kind of party, pass the watering hole where Sam gave his speech, and tears fill Sonny’s eyes. He cries for Sam, for Ruth, for himself, for the fading past.

This may be the best thing you’ve written for this site yet.

When I showed Last Picture Show to Dr. Genius, it was only halfway through, when some breasts are bared, that she realized the film wasn’t shot in the 40s. That’s how convincing it is. Last Picture Show starts and you’re in it. You aren’t watching a movie.

Everything about it is brilliant.

why thank you, sir. it is an inspiring movie.

catching up on a few post. This was a great read.

Another one of the films mentioned in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders and Raging Bulls I think, still not watched it.

oh yeah, Bogdanovich’s insanity is all over that book. and as you may have gleaned from this post, i highly recommend watching this movie. (well, after you watch Time Bandits, anyway).

I saw Peter Bogdanovich present Targets and The Lady From Shanghai at the Alamo Drafthouse in Austin, TX. Targets was great. The other was not as memorable, though he did say that it marked the end of his relationship with Cybil Shepard. I’m pretty sure he said it had something to do with the prostitutes in Shanghai. Anyway, I always thought Paper Moon was his best, but it’s been about a decade since I’ve seen either that or The Last Picture Show. I think I need to rewatch both. (PS, even more memorable than Targets may have been his impressions of Cary Grant and Orson Welles.)

He’s a great story-teller for sure, always fun to hear him talk about the old days. I re-watched Paper Moon recently and didn’t like it nearly as much as I remembered liking it long ago. Something about it felt a bit fake. But surely it’d be an excellent double bill with Last Picture Show.

Hmm… I think your memory may be off? Lady From Shanghai is a 1947 Orson Welles film — and it’s fantastic. I can picture that being a double feature with Targets but not how Bogdanovich could blame Shanghai for his break up with Shepard. If memory serves, he broke up with Shepard for Dorothy Stratton, who was then murdered by her husband.

Targets I haven’t seen. Paper Moon is pretty good but you’ll want to watch Last Picture Show again. It’s in a whole other league of filmmaking.

BTW, read your piece on Affleck on your blog. I think it’s all got something to do with our immediate gratification culture and I’m trying to find the time to write something coherent about it…

Wow, yeah. Completely. It was Saint Jack, and Singapore, not Shanghai. And the way he told the story, he didn’t break up with her. She’d had enough of him. More specifically, if my memory serves (I know I haven’t give you much reason to trust it, but . . . ), she was tired of his promiscuous tendencies. I think we both want another source before we trust my memory on this, but I’m not completely making it up.

By “we both,” I mean “we all.” And by “promiscuous tendencies,” I mean I think he suggested (without outright admitting) that he was getting it on with some of the prostitutes he used while filming the movie. Anyway, I’m looking forward to seeing those other two Bogdanovich movies again. I only saw them each once.