Holy shitballs! I am exceptionally happy to offer up this week’s Stand By For Mind Control Double Feature. Positively giddy! I’m like a schoolgirl with a throat full of bourbon bouncing on one of those horse contraptions outside the supermarket!

Why am I so happy?

It’s because normally our double features bring some under appreciated cinematic marvel to your attention. This week, however, I’m giving you two of the best goddamned films ever made. Not only they are both easily among my favorites, but they pair together so well it’s illicitly thrilling! Kind of like bouncing on one of those horse contraptions with a bourbon-soaked schoolgirl? Or perhaps not that illicit but conceivably more thrilling. It depends on your ethics, I suppose.

But enough hyperbole. On to the theme of this week’s pairing, which is ethical quandaries and giant fireball explosions! Except not so many giant fireball explosions. None, really. Sorry. I got excited.

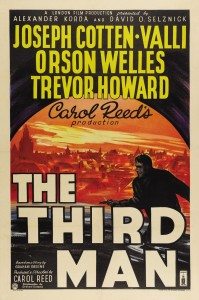

The Third Man

If you have never seen The Third Man then you are about to have a new favorite film. And a renewed appreciation for the zither.

If you have never seen The Third Man then you are about to have a new favorite film. And a renewed appreciation for the zither.

This post-war puzzler tells the story of pulp author Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten). Holly heads to a Vienna to meet his friend Harry Lime. Harry has promised Holly a job but there’s a problem. Harry’s dead.

From there, things just get more muddled, ethics-wise. Vienna was at that time a city divided between British, American, Russian, and French zones. It was rife with black marketeers and other carrion crows. This moral darkness is reflected in the film’s decidedly noir style. Black shadows overtake the screen, slashed with blinding daggers of light. Dutch angles* roll you down slopes of debris and into the maze of sewers, where any number of rats might scurry for survival.

In fact, watching The Third Man, you might see the imposing Orson Welles appear on screen, recall his films The Lady from Shanghai and Citizen Kane, and assume he’s the man who called the stunningly dramatic shots here, too.

Not so.

The Third Man is directed by Carol Reed, an English director with almost 40 years of credits to his name (and he’s as male as Holly Martins, in case you’re wondering). The script is by Graham Greene with one notable ad lib by Orson about the Swiss—which by the way, isn’t factually correct.

Yep. The Third Man is Reed’s masterpiece. It’s his diabolically thorough threshing of the wheat from the chaff—if the wheat is duty and the chaff is desire. So to say; how do you decide where your loyalties lie when your interests pull you to pieces like, well, a city divided by conquerors.

In The Third Man, Holly Martins finds odd inconsistencies in the tale of buddy Lime’s demise. Some say he was struck by a car and carried from the street by two Samaritans. Others avow there was a third man. Martins’ unwelcome investigation leads him nowhere nice—but then this is a curiously flavored noir and happy endings aren’t their usual nightcap.

There are some films that manage to tell a cracking story. There are others that grab you by the eyeballs and entice you to paw the screen. Some others have something surprising to say, something that will crawl into a dark corner of your brain to lay its eggs. The Third Man and this next feature do all three.

While watching The Third Man you have an extra-credit assignment. I want you to step into Holly Martins’ shoes. I want you think about how far you’d go for a friend like Harry and when—or if, perhaps—you’d call it quits. Take a mental picture of the very last scene too and then I want you to watch…

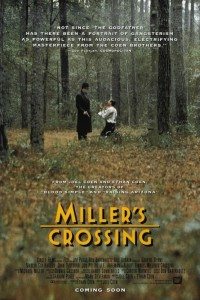

Miller’s Crossing

As much as I love The Third Man, Miller’s Crossing is my favorite. Not of the two, but of all films. I will most likely have to write a much longer post about why someday, but for now, it demands to follow The Third Man.

As much as I love The Third Man, Miller’s Crossing is my favorite. Not of the two, but of all films. I will most likely have to write a much longer post about why someday, but for now, it demands to follow The Third Man.

It is, in many ways, a reflection of Carol Reed’s gift to cinema.

Now that may seem like surprising news to you if you know anything about this Coen Brother’s feature, but it is the truth.

Miller’s Crossing is, like The Third Man, all about ethical quandaries. In fact, from the very beginning of the flawless script, the subject is set before us.

Caspar: I’m talkin’ about friendship. I’m talkin’ about character. I’m talkin’ about… Hell, Leo, I ain’t embarrassed to use the word. I’m talkin’ about ethics.

Maybe that’s why I like you, Tom. I’ve never met anyone who made being a son of a bitch such a point of pride.

Where The Third Man is an old school noir, Miller’s Crossing is neo-noir. It’s actually based on Dashiell Hammett’s hardboiled detective novel The Glass Key (which was filmed in 1942 with Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake), but it doesn’t stick too close to the source.

The Coens here instead spin a complicated story about one Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne), chief advisor to Irish-American Prohibition-era mob boss Leo (Albert Finney). Leo kicks the film off by ignoring some of Tom’s advice. As a result, they end up competing with a rival Italian mob for control of their unnamed city (perhaps an oddly unpopulated New Orleans).

What’s the rumpus, you ask? Leo’s gone squirrelly over Verna (Marcia Gay Harden), whose brother, Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro), sold out a fixed fight. Are you already confused. If so, them’s the breaks. Miller’s Crossing moves fast and doesn’t hang about for you to catch up.

The good news is that everything you need to know to fully comprehend each and every goings-on is in the script. The bad news is that each and every line of dialogue is telling you something you oughta know.

Repeated viewings are advised.

Not that you won’t love Miller’s Crossing the first run through; you’ll just love it more and more as you glean increased levels of meaning from the movie.

But ethics. That’s what Miller’s Crossing is about. Tom’s loyalties get twisted as he tries to pull Leo’s bacon out of the fire. The choices he makes—whether driven by duty or desire or both—are all a matter of ethics, which are as clear as mud. Sometimes, we don’t know why we make the decisions we do. And sometimes, we do the right things for the wrong reasons or vice versa.

There are many points at which Miller’s Crossing parallels The Third Man, but it’s hard to detail them without giving the game away. Keep an eye out for dead men on the move, unwilling executioners, and men whose actions find justification only when they’re already underway.

Then, of course, there’s the final scene. In The Third Man, Holly stands by the side of the road, under the looming trees, in the moments following the funeral of a man he’s killed. Despite his hopes, romance passes him by without a word; that’s the price he pays for making ethical choices in fractured world.

In Miller’s Crossing, the homage to Carol Reed’s film is clear. Tom Reagan stands by the side of the road, under the looming trees, in the moments following the funeral of a man he’s killed.

What happens next? Watch and see and wonder. Let those mind-eggs hatch. Ask yourself: how are Holly Martins and Tom Reagan the same and what separates them? Some interpret what Tom does in the end of Miller’s Crossing as a nihilist statement, but that’s not the film I’m watching. I think he’s judged his own ethical choices and found himself wanting. His last choice is to pass himself by.

No matter how good our intentions, in the end, some things can’t be forgiven. Make your choices and live with them.

And you should choose to watch these two films in a row.

* Meaning the camera is tilted off from level, so one side of the frame is higher than the other. The term comes from Deutsch, meaning ‘German’ and it was a technique developed in early German Expressionist films, like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which is pretty awesome, too.

i watched Miller’s Crossing again a couple weeks ago. best Coen Bros. movie of them all. “We only take yeggs what’s been to college!”

Undoubtedly. Although I’m overdue for a screening of Blood Simple. And Barton Fink.

Watched Raising Arizona not too long back. It just didn’t wow me like it used to. Perhaps that’s because I have all the lines memorized…

A vote for Barton Fink here.

Not that close for me, actually.

That’s just because you like the cry of the fishmongers. And you’ve got that head in box.

Barton Fink is a close second for me. if not a tie with Miller’s Crossing. and i still love Raising Arizona, even though i too have the entire thing memorized.

It’s hard to watch Miller’s Crossing and Barton Fink and then get excited about films like Argo.

I also feel the need to wave the Blood Simple flag. I need to watch that again but there are so many films I haven’t watched for the first time yet… almost through with everything on our I Like to Watch list. Last Year at Marienbad and The Passenger currently on the coffee table.

I’d be interested to read a post of why you think ethics is the driving force behind Tom’s choices. Or better yet, HOW you think Reagan interprets his own ethical dilemma.

He states his motivations throughout the movie, that his intentions are based on “the smart play” and “reasons… it helps to have them.” He is a purely intellectual creature in a world of folks motivated by feelings and morals and so on.

I mean, just watch what happens to him when he loses his hat (i.e. head) in the movie.

I mean, that line: “What heart?”

Well, Mister Dribble, it has been a long time since I’ve watched this for the 40th time and since I wrote this, but my short answer would be there are the things we say and the things we do. He says it’s about the smart play, and he can justify his actions that way, but we don’t act from the head–any of us–we decide based on emotions and then use the details to back up our feelings. In Tom’s case, his struggle to align what he feels/wants and what he thinks, leaves him with a series of ethical dilemmas. As to HOW he interprets them, yes: that would be interesting to write and read. I think he’s smart enough to see how he’s being influenced by his emotions and smart enough to stay a quarter-step ahead of them, but pandemic life deprives me of the time to rewatch or write more. If you judge Tom by his actions alone, what do you see?