I went to see Zero Dark Thirty on Friday with the Supreme Being. Since then, he’s written an excellently insightful review of what director Kathryn Bigelow did with the film. I’ve also been thinking—not about what Bigelow did, but about what she didn’t do and about what those absences and oddities mean, intentional or not.

That’s what I want to talk to you about, because I believe Zero Dark Thirty is as fascinating a film as you’re likely to see. Even though, when you watch it, you’d be forgiven for completely failing to find anything of interest within it.

The film recounts in painfully complete and possibly accurate detail how the labors of one C.I.A. agent eventually led to the assassination of Osama bin Laden.

But what is it about?

The film opens with jumbled audio over black, snippets of sound from September 11th, 2001. The next scene is one of a prisoner being beaten, mistreated, humiliated, and tortured by a veteran C.I.A. agent (Jason Clarke as Dan) while a fresh, willowy woman (Jessica Chastain as Maya) observes uncomfortably.

This is what we have come to, the film says. From A we get B. Simple associative editing.

We were attacked. Our feelings of confusion and vulnerability led us to a dark room. In it, we set the beautiful promise of America against the soiled refuse of the enemy. What is it we expected to happen in that room, though? What is it you would do, standing there—a mask to disguise yourself if you want—while your mentor intentionally caused anguish?

Will this man ever be released? No. Question asked and answered.

So. Regardless of what Bigelow meant or didn’t mean with these scenes, she’s set up an engaging question. It is not, “are we in support of torture” as so many critics suggest, but instead “you armchair quarterbacks, you self-proclaimed saints, what would you have done if you were in that dark room?”

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying the characters in this movie—because regardless of its roots in real life, fiction is what this is—made the right decisions. (I don’t know and don’t care if Maya is based on a real woman or not. That’s not part of the film.) What I’m saying is, “Look at this. This is what we accept as real.”

A woman, with a task, in a room. She does as expected, we have Zero Dark Thirty. She makes a different series of decisions and most likely bin Ladin continues to live in a windowless home, his own jailor.

So it’s only the story of the hunt for and killing of bin Laden on the surface. The story I unearth within—perhaps inventively—is about the character traits that led to his notable death.

There are words—easy to say—and then there are actions, which are simultaneously impossible and all too easy to perform. And we watch as Maya becomes comfortable with torture and interrogation. We watch as the beautiful promise of America crawls deep into Al Qaeda’s ass to root out the tumor of violence. Maya soils herself—eventually willingly and completely—so that she, and you, might throw off the confusion and vulnerability of 9/11. So that we might relieve ourselves of our onerous duty, which is called revenge or self-preservation, depending on your perspective.

There are words—easy to say—and then there are actions, which are simultaneously impossible and all too easy to perform. And we watch as Maya becomes comfortable with torture and interrogation. We watch as the beautiful promise of America crawls deep into Al Qaeda’s ass to root out the tumor of violence. Maya soils herself—eventually willingly and completely—so that she, and you, might throw off the confusion and vulnerability of 9/11. So that we might relieve ourselves of our onerous duty, which is called revenge or self-preservation, depending on your perspective.

That’s a fascinating story.

Is it the one Zero Dark Thirty tells? If so, almost definitely it does so only accidentally. And yet, the story is there. For if you watch this movie and think only, “Yep. That’s how we tracked down that dirty bastard bin Laden,” then you are as devoid of opinion as the film purports to be.

Turned that one around on you, huh?

It is our job, as consumers of film, to develop opinions. Specifically, it is my job. I do not give a rat’s ass what Bigelow said she was trying to do vis-a-vis impartiality, or—for that matter—what scenes Tarantino had to cut in Django, or what studio malarky went on developing The Hobbit films. I care about what I see and what I can take away. Even if what I take away I have to take by force.

There were many, many scenes in Zero Dark Thirty that said nothing, that went nowhere, and which maddened me with their droning boredom. And yet; isn’t that as it should be? If we are Maya, how do we become the woman who hopes for nothing more than the death of a man she has never met? A man who has no lines in the film. A man whose face is barely even seen.

Does Maya’s tenacity—perhaps the only truly convincing element of Zero Dark Thirty—leave any room for awareness of her actions? As she slogs through endless live and videotaped interrogations, both actors and observers become numb to the ‘reality’ of what we see. It is just another man with foreign name being abused. We don’t care about him; he is boring. His suffering is boring. We only want progress. Can we—through the use of torture or any other means—advance this plot? If so, by all means go right ahead. I want results and I want them faster than Zero Dark Thirty offers them. It’s subversive. By being so dull, the film makes you complicit in Maya’s increasingly questionable choices.

Does Maya’s tenacity—perhaps the only truly convincing element of Zero Dark Thirty—leave any room for awareness of her actions? As she slogs through endless live and videotaped interrogations, both actors and observers become numb to the ‘reality’ of what we see. It is just another man with foreign name being abused. We don’t care about him; he is boring. His suffering is boring. We only want progress. Can we—through the use of torture or any other means—advance this plot? If so, by all means go right ahead. I want results and I want them faster than Zero Dark Thirty offers them. It’s subversive. By being so dull, the film makes you complicit in Maya’s increasingly questionable choices.

Inuring, that’s what Zero Dark Thirty is. That is what dirty jobs must be if they are to get done—which, in this case, you must admit they did.

As Maya digs deeper into the filth, the world endures terror events. Some of them even reach out to touch her personally. The hotel she is drinking in gets bombed. Her friend Jessica (Jennifer Ehle) is killed while they are in communication. Their excitement at finding a potentially important source is expressed through the coldness of text messages, which simply stop.

Your friend is dead. You have no new messages.

Suffering in Zero Dark Thirty is a lack of news. In the wake of Jennifer’s death, Maya goes fetal. Is she mourning her friend or yet another setback? She did not seem to particularly care for Jennifer, or anyone. So why is she so sad and, yes, angry? Because her abhorrent duty continues. The film must go on.

Suffering in Zero Dark Thirty is a lack of news. In the wake of Jennifer’s death, Maya goes fetal. Is she mourning her friend or yet another setback? She did not seem to particularly care for Jennifer, or anyone. So why is she so sad and, yes, angry? Because her abhorrent duty continues. The film must go on.

Isn’t that a bit how you feel upon reading of a bombing in some foreign city? Something terrible has happened to people you only care about abstractly. And you are reminded that terrible things continue to happen. Someone—Maya perhaps—will have to do something about them. You are reminded of the ongoing disaster of the world and it makes you sad and angry. Again and again.

You have no new messages.

Care for as long as your attention span and memory allow and then do something else. For if you are watching Zero Dark Thirty and drifting off, imagine what it must have been like to be one of those C.I.A. agents. Stuck in a never-ending film, and one with almost no hope of a happy ending.

And people are shocked—shocked!—that prisoners were mistreated. Well what did you expect?

Zero Dark Thirty is also fascinating in its scale. I do not mean its thirty-thousand foot high perspective, one of remove, which skirts any judgement or statement about the actions of its characters. I speak of the scope of the United States’ hunt for Osama bin Laden as depicted in the film.

“There’s nobody else, hidden away on some other floor. This is just us. And we are failing.” says C.I.A. chief George (Mark Strong), reminding his pathetically small team that they are the only ones on the job. There is no special team of ninjas and hackers devoted to rooting out bin Laden. We only get Coach Taylor from Friday Night Lights and Michael from Lost. We have a handful of tired spooks motivated primarily by Maya and her relentless gnawing.

Let us consider that. Can we find a keener reflection of our national identity and culpability? You and I sit and watch a film about the assassination of one of our country’s only successful attackers. Before you read the headline that Osama bin Laden had been killed, did you even care? Did you demand that we hunt that bastard down, commit your willing support, donate extra in taxes, stand up for whatever disgraceful methods were employed so that we might free ourselves from confusion and vulnerability?

No. You fucking didn’t. You gave up on that ages ago. So then what is there to celebrate in “the greatest manhunt in history?” Unless you are Maya. And why does Maya care except that, unwillingly assigned the task, she did as most humans would—she accepted responsibility and began to invest of herself.

Does that make her a hero or a villain? Is, in fact, Zero Dark Thirty a tragedy of our own making? Is Bigelow reading us the charges in our own arraignment?

If so, must we not plead guilty?

Not yet. First, we reach the end of our tale. In which Maya’s efforts—tedious, unsupported, and apparently even largely unimportant—miraculously lead to what may actually be the location of Osama bin Laden. A team of SEALs gets sent in because the alternative is equally risky politically.

What, we ask, is their motivation?

Because at no point throughout the film does anyone but Maya express any personal interest in finding or killing Osama bin Laden.

People work towards that goal, as you work to fill out TPS reports or ready your next release or unload a truck. Only Maya, in the aftermath of Jennifer’s pointless and avoidable death, swears she will see bin Laden and everyone involved killed. Everyone else—up the chain to the President presumably—doesn’t really care. Watching the film, I don’t really care except that I know I cannot leave the theater until bin Laden is killed. His death is just a task on a list, and one put there long ago at that.

I’ll repeat that: His death is just a task on a list.

And that’s something we all must take responsibility for, for we put his name on that list. Maya works for us on assignment. It is our fault that there is such a film as Zero Dark Thirty. And you thought the film was boring and pointless. What if, instead, it is unintentionally brilliant? What if, instead, its ham-fisted style and interminable length and loathsome characters are exactly what we deserve? What if Zero Dark Thirty is the sentence for our crimes?

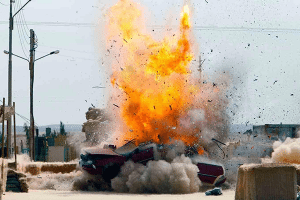

We get to watch the dullest raid in the history of cinematic raids, because getting any pleasure from bin Laden’s death would be ghoulish. There is no real drama, and less heroism. Yeah, one guy in the compound had a gun and pounded out a few errant shots. Sure, some locals came out to investigate and the Pakistanis scrambled some jets. One helicopter crashed, too, and had to be torched. You’re bored? Too bad. This is what you ordered. What did you expect? The end of Skyfall? How would that come to be in a real world? Osama bin Laden, in the end, was as difficult to kill as M. An elderly person sitting at home, waiting and resigned.

We get to watch the dullest raid in the history of cinematic raids, because getting any pleasure from bin Laden’s death would be ghoulish. There is no real drama, and less heroism. Yeah, one guy in the compound had a gun and pounded out a few errant shots. Sure, some locals came out to investigate and the Pakistanis scrambled some jets. One helicopter crashed, too, and had to be torched. You’re bored? Too bad. This is what you ordered. What did you expect? The end of Skyfall? How would that come to be in a real world? Osama bin Laden, in the end, was as difficult to kill as M. An elderly person sitting at home, waiting and resigned.

Hooray! We did it! We killed that fucker!

The result is the last fascinating thing about Zero Dark Thirty. There is no celebration. In what is ostensibly a film about the earthshaking manhunt for and assassination of a national enemy, not a single person says anything laudatory about the effort. Not a word. There is no, “We couldn’t have done it without you, Maya,” or “We’ll finally be able to sleep easy tonight,” or even, “First round’s on me!”

The SEAL who fired the actual shot confesses in trepidation, “I’m the one who got the third floor guy.” When Maya boards her plane home, she is told she must be someone special as the whole plane is just for her. That’s it. The celebration of bin Ladin’s death is a single tear rolling down Maya’s cheek in the back of an empty cargo plane, with no explanation offered.

Because she’s done what she was asked to do. With zero awareness, she forced her dark hope into fruition. And only then does the film’s thirty-thousand foot view snap in to show in close up who Maya is and what she is responsible for.

She is us. We are her.

First round’s on me.

I double-dog dare Bigelow to take on Tora Bora and throw in John Walker Lindh for good measure. Now that’s a morally ambiguous Spaghetti Western I can sink my teeth into.

I can certainly get behind reviewing such a film…

Btw, I love your revisionist look at Zero Dark Thirty. Your story is compelling; if only the producers had envisioned it, too.

Thanks!