The best way to learn how not to make a movie is, nine times out of ten, to watch a movie. Lessons will be readily evident. For as many great movies as have been made, bad ones outnumber them by a vast margin. So it goes in the arts. As put memorably by Theodore Sturgeon, to the point where it’s now referred to as Sturgeon’s Law: “Ninety percent of everything is crap.”

The thing about crap, though, is it can be awfully entertaining. And I don’t use the word “awfully” by accident. Some of the worst movies ever made were made with just as much love, passion, and vision as the best. The artists involved had big ideas. Important ideas. And if those important ideas include Bela Lugosi wrestling a giant octopus in a swamp or a dream sequence featuring a little person in a blue tophat, who are we to judge?

This week’s double feature does not feature bad movies by inspired (or insane) artists. It features instead two movies about making bad movies, the first about a man often called the worst director in the history of cinema, the second a look at everything that can, and often does, go wrong when making a movie.

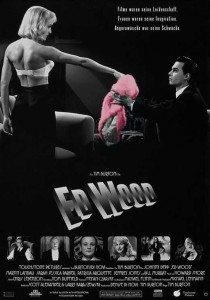

Ed Wood (’94)

Tim Burton started strong as a director. Many (myself included) would say his first film, Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, is his best. His second best is his is second film, Beetlejuice (a sequel is said to be in the works; I will assume the worst). For his third, he went the big-budget studio route and made Batman (’89). The production was said to be a nightmare of epic proportions. Fans of the dark knight were outraged that Michael Keaton was going to be a superhero. And music by Prince? All were dubious. It was a hit anyway, a huge one.

Burton needed a respite from that insane production, so next he made a very personal film in Edward Scissorhands. Not bad, but still a step down from Beetlejuice and Pee-Wee’s. Then he made Batman Returns, and danced in a soothing rain of money.

Once again he followed up the big studio picture with something smaller: a biopic of notorious director Ed Wood, Jr., famed for making the oft-cited “worst movie ever,” Plan 9 From Outer Space (’56), the cross-dressing classic, Glen or Glenda (’53), and still others. Burton insisted it be shot in black & white, scaring off most studios. Disney went along with him, giving him complete creative control and a modest budget of 18 million. Johnny Depp signed on to play the cross-dressing director immediately.

The thing about Ed Wood is that he was an incredibly upbeat, positive guy, despite never finding the fame he was after. He really thought he was making the next Citizen Kane in Plan 9. Burton chose to leave out the darkest moments of Wood’s life. He wanted the movie to play the way it might have been seen through Wood’s own eyes. There’s an almost ‘50ish TV show quality to the movie and to some of its characters, most notably Wood’s girlfriend Dolores (Sarah Jessica Parker). Depp plays Wood as a guy who just wants to show his art to the world, a guy who’s blissfully unaware of how the world at large sees him. He plays him like any other dreamer. That this particular dreamer made beautifully awful movies is beside the point.

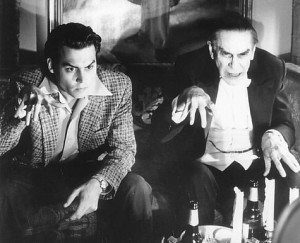

Martin Landau gives an inspired performance as Bela Lugosi, a washed up star at the time of Plan 9, which would be his final film. Lugosi died before Wood had finished shooting it. His character was played by another actor (or actually not an actor at all, but a chiropractor Dolores knew) who kept a cape over his face the whole time. Yeah. If you haven’t seen Plan 9, you might to remedy that in a hurry.

Landau won an Oscar for his role. His Lugosi is bitter, sad, addicted to morphine, and completely lovable. Every scene he’s in kills. Including the one where he wrestles the octopus, which if that’s not art, I don’t know what is.

Bill Murray shows up as Wood’s gay friend Bunny Breckinridge, who like most of Wood’s friends ends up with a role in Plan 9. This came during the weird phase of Murray’s career after his great comedies of the ‘80s but before his re-invention as serious-weird-sad Bill Murray beginning with Rushmore in ’98 (Groundhog Day is in there too, but not much else). Murray gives one of his great supporting roles in Ed Wood, sort of reminiscent of his part in Tootsie from way back in ’82. It’s a shame more people didn’t see him in it.

Ed Wood isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. The box office attests to that. It’s Burton’s biggest flop. He followed it up with Mars Attacks! and then an endless stream of big-budget junk he’s still floundering in. Maybe Ed Wood’s failure scared him off of making smaller, weirder movies. Yet it seems appropriate that this movie about a failed movie-maker whose movies were ignored was likewise ignored. Since it’s release it’s found a lot of love, just like Ed Wood himself.

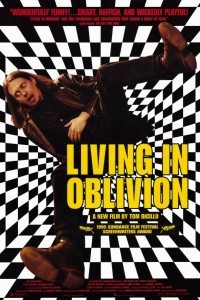

Living In Oblivion (’95)

There is no better movie than Tom DiCillo’s comedy Living In Oblivion for showing what it’s like to make an independent movie. It takes everything that could possibly go wrong on a shoot—which is everything—and runs with it like a hyperactive little kid with a pair of mommy’s gardening shears. Needless to say, eyes are put out. Metaphorically speaking.

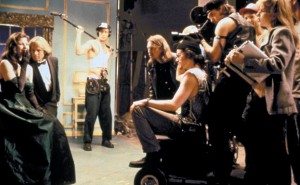

The movie takes places in three distinct segments, the exact nature of which I won’t spoil. Steve Buscemi plays the director, Catherine Keener is the female lead, James LeGros is the male lead, and Delrot Mulroney is the cinematographer. Each segment focuses on a single scene and everything in it that could possibly be fucked up, from tiny technical issues to actors’ insanity and insecurity, to the director giving up on the very concept of filmmaking, to crew member’s affairs coming to light, to an enraged dwarf lambasting the production for, um, small-mindedness in dream scene conception.

The segment featuring LeGros as Chad is priceless. He’s the consummate ego-driven idiot. Rumors long-swirled that he was based on Brad Pitt, who starred in DeCillo’s first film, Johnny Suede, before becoming a star. Apparently DiCillo debunks this theory on the DVD commentary track. But I prefer to believe he’s just covering his ass, and will always believe that Chad is Brad.

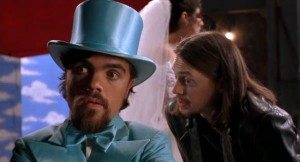

The final segment is owned by Peter Dinklage as Tito, the angry dream sequence dwarf. He looks adorable in his baby-blue suit and top hat.

When shooting in any location, at some point the sound-recordist will need to capture at least 30 seconds of “room tone,” which is simply the sound of the room without anyone talking or moving around. This usually takes place when everything in a given location has been shot. The last shot is finished, and just as everyone scurries to pack up, they’re reminded to shut up for room tone. Everyone stops what they’re doing, stands frozen and silent. Waiting. Thinking. Dreaming. On any set, it’s a strangely beautiful, reflective moment. Living In Oblivion includes this in a way that feels exactly real. I love it for that.

If there’s one subject movie-makers make too many goddamn movies about, it’s the act of movie-making. It’s what they know, after all. Ninety percent of such movies are crap. Ed Wood and Living In Oblivion reside at the top of the other, rarified ten percent. Watch them, laugh your ass all the way off and back on again, and fear to ever make a movie yourself…

i love that you’ve mistyped “dermot mulroney” as “delrot.” delrot is a much better name. we should send him a letter about it.

great, now i can’t fix it. your comment has permanently enshrined it for all time! delrot is going to kick my ass…