It’s been a long time, too long, since my brain has been as weirdly and intensely affected by a new movie as it was last night at a screening of Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color (’13). It’s a disturbing, hallucinogenic, oblique tale of, at its core, two shattered people coming together and learning how to reconstruct the very definition of who they are. I think. The literal narrative is fractured but in its way straightforward. By the end, you more or less know what events have taken place, and how those events flow together, cause and effect-wise (with an emphasis on the “more or less”). It’s just that why they took place and what they mean is wide open for interpretation.

I’m not sure how to write about Upstream Color. Carruth has said the movie is unspoilable. And he’s right. Nothing I can say about it is going to ruin it or give anything away. How do you give away a movie that demands each viewer determine for themselves what it means? Nevertheless, I’m going to be sparse with story details. The less you know going in, the better the experience is going to be.

Upstream Color is only Carruth’s second movie. His first was Primer in 2004, a time travel story that plays as if it was made not for an audience to watch but for the characters themselves, who talk to each other as if no one was listening, who don’t explain a thing; they know exactly what they’re talking about (for example, the words “time travel” are never spoken). Slowly but surely, you get a handle on what’s happening in Primer. At least generally. Specifically, as soon as you think you know what’s going on, you find you don’t. More details are alluded to. Nothing is clarified. By the end the confusion is overwhelming, leaving one scratching one’s head, but kind of pleased just the same. It’s a short, odd movie not easily forgotten.

Carruth spent years after that trying to get a movie called A Topiary made, with no luck. He switched to a new idea, and Upstream Color was born.

In a Q&A following the screening (thanks, SFFS and Roxie Theater!) Carruth said he thinks of Primer as a very rough movie (it is) and that to him it resembles Upstream Color not at all, that if it weren’t for his being in both movies, no viewer would ever connect the two. Which is crazy. Artistically crazy, absolutely, but crazy. Upstream Color is far more accomplished and beautiful and professional and thoughtful and intentional than Primer, so I’m not surprised Carruth feels the two movies don’t resemble one another. But they do. One of the joys of both movies is in seeing such an individual style on display, one that’s evolved hugely, but that’s instantly recognizable.

So what the hell is Upstream Color? To begin with, it’s very creepy. It stars Amy Seimetz as Kris. She’s the center of gravity. Her performance is intense. The role requires a lot of her. She needs to hold your focus in a story that bobs and weaves and defies easy understanding, and this she does. Something happens to her at the outset. Well, something is done to her. It’s best not to know what in advance. The thing that happens is easy to grasp on a literal level, but it’s thick with metaphorical reverberations. Which can be said of the entire movie. As a result, her life is drastically altered. She is a broken woman.

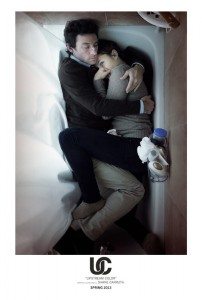

Kris meets Jeff (Shane Carruth) on a train. He too seems broken. In fact it seems like he must have undergone a similar if not identical experience to hers. What exactly was that experience? We see it, but surely what’s shown is a metaphor for something else, something that destroyed who they were and forced them to start over, as though they’d been addicted to drugs or brainwashed by a religious cult or controlled from afar by an alien consciousness and only just now been released and granted free will. Their relationship grows, to the point where they begin to confuse one another’s pasts for their own. Eventually they come to understand what was done to them, at least in the literal sense. They confront what happened. A resolution is found.

How’s that for not giving too much away? I will only add that mysterious worms and pigs are involved in a major way, as is Thoreau’s Walden.

Its literal story aside, what Upstream Color manages to do is allude metaphorically to all sorts of different ideas: to love, pregnancy, addiction, cancer, shared consciousness, and probably other things too, yet without ever being exactly a metaphor for any of them. This works because of what to me feels like a very precise understanding on Carruth’s part of what the story means to him, of what fits and what doesn’t fit, whether or not he could put (or would even want to put) that meaning into words. Nothing in the movie feels out of place, or put there merely to add to the mystery. Every element feels purposeful and related. This is hard to pull off. Who else does this? David Lynch comes to mind. David Cronenberg, at times. And Terrence Malick. These are filmmakers who allow their subconscious to play a role in how their work is shaped, resulting in films with focused yet widely interpretable meanings.

The other similarity to Malick is Carruth’s camerawork and the editing, done by Carruth and David Lowery. With little dialogue, the film is pushed forward with an often moving camera, close-ups of faces, hands, and objects, key elements left just out of frame, and a flowing editing style that focuses on matching movements from cut to cut. An hypnotic quality is the result. Adding to this is the score, composed by multi-tasking Carruth (who said he’d been a control freak on Primer by necessity and on Upstream by choice), with its sweeping, loud synthesizer washes topped by fragile piano melodies. And the sound design. One of the characters (called only The Sampler, played by Andrew Sensenig) records and manipulates sound. Why he does this isn’t entirely clear (he’s also the one who knows how to handle the worms, and looks after the pigs). Deep, echoing sounds, as though heard from underwater, fill the movie and add to its overall unsettling vibe.

Which that’s another thing about Upstream Color. You’re going to feel unsettled watching it. It’s unnerving. In part because of the seriously disturbing first third of the movie, in part because of how little is explained, and in part because of the music and sound. For that matter, it’s unnerving because of all of the above, the metaphorical resonances, the broken characters, sad and confused, slowly allowing themselves to open up to one another, and the film’s serious tone. One thing Upstream Color does not feature is comedy. I don’t think there’s a single laugh in the movie. One image, however, will bring a smile to your face. It’s the final image of the film. I hope this reassures you.

The movie looks beautiful. The color scheme with its focus on blues and yellows is very deliberate and it too creates free-flowing connections. I was reminded of the blue flowers at the center of Philip K. Dick’s book A Scanner Darkly. Not sure if Carruth had this in mind, but that’s where my brain wanders when I think about bright blue hallucinogenic flowers.

It’s a rare movie that’s able to feel so acutely resonant with meaning while keeping its meaning open to interpretation, that is able to tell a story that feels like it makes sense on the surface, but that when its particulars and characters are more closely examined, seem not to exist but as metaphors for something far more universal and wholly interior. When the screening ended, and after Carruth had talked for a half hour, he announced that they’d be running the movie again right then for anyone interested. Many were. It was almost midnight, so I left. Any earlier and I would have stayed. It’s that strange and compelling.

When it opens in April I’ll be seeing Upstream Color again. It’s the best new movie I’ve seen in ages. I’ll be surprised (and overjoyed!) should anything better open this year. Shane Carruth just shot to the top of my list of directors whose next movies I can’t wait to see. Find out where it’s playing and see for yourself. It’s weird movies like this that need your support.

UPDATE: Go here for an interview with Andrew Sensenig, who plays The Sampler.