I adore Full Metal Jacket even though it is, clearly, a difficult film to keep company with. The film is not Stanley Kubrick’s most cohesive effort or his most accessible. It is, however, a film that skritches around inside your skull like a hive of burrowing insects—bugs that are consumed with an insatiable hunger for dark thoughts and the clarity that follows them.

I adore Full Metal Jacket even though it is, clearly, a difficult film to keep company with. The film is not Stanley Kubrick’s most cohesive effort or his most accessible. It is, however, a film that skritches around inside your skull like a hive of burrowing insects—bugs that are consumed with an insatiable hunger for dark thoughts and the clarity that follows them.

I watch it and I am in a world of shit. But I am alive and I am not afraid.

Today I’d like to do two things. First, I’d like to quickly give an overview of what the film lays out. Then I’d like to dissect a scene from it, as an example of what it delivers on a more intimate scale. I will be addressing you as if you have seen Full Metal Jacket, so if you haven’t, don’t expect me to play cagey with plot details.

Knowing what does or does not occur during the course of the film will not spoil anything anyway—any more than knowing that Nixon got impeached will spoil All the President’s Men.

This is not a film about things happening in the external world. It is a film about men changing inside their heads. Their actions only reflect their inner turmoil.

Animal Mother quotes the Bhagavad Gita on his helmet, which reads, “I am Become Death.”

He isn’t full of shit, either. You can tell from his war face.

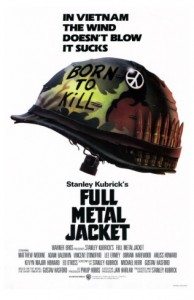

Chapter One: Born to Kill

Full Metal Jacket, released in 1987, appears to be a war film. That’s how people generally talk about it. It is not a war film, though. It is a film about releasing the killer inside of you. It is a film about survival and hostility and the abyss beyond your self. It only happens to take place during a war—and even then only half of it directly is set during the martial conflict in Viet Nam. The war serves as a stark (and perfect) example of the morass which human society can become and of how one’s morality can be disassembled and laid out for inspection like the pieces of a rifle.

The film is split into two parts. In the first, Matthew Modine’s lead character, Joker, joins a platoon of new recruits for Marine training at Parris Island.

The film is split into two parts. In the first, Matthew Modine’s lead character, Joker, joins a platoon of new recruits for Marine training at Parris Island.

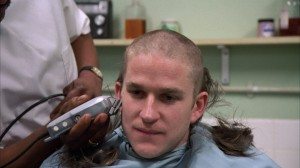

In this half of the film, Lee Ermey’s Gunnery Sergeant Hartman methodically obliterates his charges’ individuality—training them to be killers. From the first shots of men being shorn of hair to the final fade to black, this chapter of Full Metal Jacket is as on target as a sniper’s greeting.

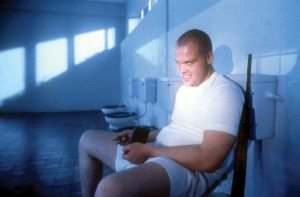

Joker struggles—along with his platoon-mates—to allow his war face to crack through without ceding his identity. The tempering process is psyche-shattering by design. Private Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio) fights his own transition with natural, good-natured incompetence. His failures reflect on the other recruits, though, and they get punished in his stead. So they resent him and beat him. Being shown the cleansing efficacy of violence, Pyle locates the killer locked behind his hapless mug. He becomes a Marine and does what Marines do. He kills his enemies—Sergeant Hartman and then himself. To pass through the trauma, he opts to kill the half of himself he cannot bear.

Despite barely passing basic training, Pyle proves that he has thoroughly assimilated his lessons—much more thoroughly than Joker. Good job, Pyle!

He closes this chapter by revealing his war face—and what a war face it is! Seeing D’Onofrio’s fully unhinged character enact his dance of violence is as frightening as anything in The Shining. More so, as it involves no other-worldly mumbo-jumbo.

What possesses Pyle is only what Sergeant Hartman coaxed out from deep within the man’s own head.

Now, that’s stripping the whole first chapter down to its bleached bones, but it is the straight line of the tale. Men learn to become killers and killers they become. Pyle defeats his enemy and then, finally recognizing his world for the shit it is, he performs a mercy killing. He sticks the barrel of his rifle in his mouth and eats a live round—seven-six-two millimeter full metal jacket.

Chapter Two: I Am Become Death

In the second half of the film, vignettes congeal around the in-country experiences of Joker. While there is one unstoppable story in the first half, the second feels more like a fragmentation grenade.

In the second half of the film, vignettes congeal around the in-country experiences of Joker. While there is one unstoppable story in the first half, the second feels more like a fragmentation grenade.

When we catch up with him, Joker’s a reporter with Stars and Stripes in Da Nang. He and his photographer Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard) float through the war as observers, eager for action and only getting it from prostitutes and Army bureaucrats. Eventually, during the Tet offensive, the reality of the war rears its head for them. This places both men in combat with their lives at risk. It gives them the opportunity they both claimed to want: to relish bloodletting.

While this second chapter seems to be scattered and disjointed, it’s not.

Just like the first half of the film, this half is about men learning to become killers and becoming killers. The training is just more practical.

Joker distinguished himself on Parris Island, but he’s no killer, no matter what lies he feeds his colleagues. His war face remains untapped and untried—as was clearly revealed at the end of chapter one where he failed to face or save Private Pyle.

What, Kubrick posits in this second half, does it take to turn Joker into a harbinger of death?

In order to find his inner killer, our protagonist must first wallow in the amorality of the war zone. He must inure himself to everyday inhumanity—prejudice, abuse, violence, callousness. That ichor is what each of these vignettes draws us through. The stripping away of Joker’s defenses and the cauterizing of his subjective morality.

In the end, after finally finding himself intimate with death, Joker becomes a killer. He executes the teenage sniper who has shot and killed his friend Cowboy (Arliss Howard) and many others.

In the end, after finally finding himself intimate with death, Joker becomes a killer. He executes the teenage sniper who has shot and killed his friend Cowboy (Arliss Howard) and many others.

The girl is wounded, lying amid rubble and blood, begging for death, her pigtails astray. Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin), now squad leader, wants to leave her for the rats but Joker insists on showing her mercy. He cannot bear her suffering.

Joker lifts his sidearm. He struggles with the Jungian thing—the duality of man—which has led him to both wear a peace button and to scrawl “Born to Kill” on his helmet, the same dilemma that defeated Private Pyle, and he ends the girl’s life with a bullet.

So the story is over. Joker has earned his thousand-yard stare. The Marines tramp off singing the theme song to the Mickey Mouse Club and Joker’s inner monologue offers a coda:

Joker: My thoughts drift back to erect nipple wet dreams about Mary Jane Rottencrotch and the Great Homecoming Fuck Fantasy. I am so happy that I am alive, in one piece and short. I’m in a world of shit, yes. But I am alive. And I am not afraid.

Freedom? You’d better flush out your head, new guy. This isn’t about freedom; this is a slaughter. If I’m gonna get my balls blown off for a word, my word is “poontang”.

Like in the first chapter, we have found closure with a mercy killing. Pyle kills himself to escape his world of shit. Joker kills a girl, wrestling his morality amid chaos in order to survive not only physically, but spiritually.

Welcome to the company of killers.

Kubrick does not do anything as gauche as suggest whether or not Joker is admirable or despicable in his actions—the same with Pyle. They are just human beings, as are we all.

In this world of shit, Kubrick trains his camera on what creeps from your skull after your finer thoughts have been eaten away and only the bones remain.

You Owe Me for One Jelly Donut

Gunnery Sergeant Hartman: The deadliest weapon in the world is a Marine and his rifle. It is your killer instinct which must be harnessed if you expect to survive in combat. Your rifle is only a tool. It is a hard heart that kills. If your killer instincts are not clean and strong you will hesitate at the moment of truth. You will not kill. You will become dead Marines and then you will be in a world of shit because Marines are not allowed to die without permission.

In Full Metal Jacket the two sections of the film feel very different for a number of reasons. Some of these reasons are less readily apparent, such as the way the camera moves.

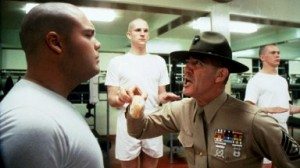

In the first half of Full Metal Jacket the camera—your aperture into the world of the film—is frequently in retreat. There are countless scenes in which Gunnery Sergeant Hartman stalks up and down the aisle of the barracks in between near-symmetrical rows of at attention Marine recruits. In these scenes, the camera moves at the same implacable speed as Lee Ermey does, and frequently away from him. As he advances, the Steadicam operator paces backwards. This makes the audience feel pursued; we cannot increase the distance between ourselves and the stalking violence of Sergeant Hartman.

(I will also point out here that Lee Ermey was, earlier in his life, a real drill instructor and that around half of his dialogue in these scenes is of his own devising. And since we’re talking actors, Vincent D’Onofrio was just a friend of Matthew Modine’s. He wasn’t an actor at all, but rather a bouncer at a bar. Kubrick cast him and he gained upwards of 70 pounds to play Private Pyle—beating the record DeNiro set for Raging Bull.)

In part two of the film, the camera chase is over. In Viet Nam it moves alongside the action, follows in its footsteps, or coaxes you and Joker into the shit.

There’s one scene in the first half of the film, however, that alters this paradigm. We’re about a quarter of the way into the film and well into the dehumanization of basic training. We start with a shot that’s similar to many others we’ve seen thus far, but subtly different.

Watch the whole thing here:

Inside the barracks the color scheme is institutional and unwell. Flourescent lights gleam off the sickly green paint of the ceiling’s support beams. Looking downwards, the walls bleach to dun and, at this level, we also find our Marine recruits. They stand in symmetrical lines atop their footlockers, dressed in white undergarments. Their fingers are held in front of them for a hygiene inspection. Sergeant Hartman paces down linoleum the color of dried blood, standing out in khaki and dark green. It looks like auditions for spots in a morgue.

Most of this is familiar, but not all. This time the camera is not centered in the aisle. It does not track back as Ermey advances. It is instead off to the side, making the clean symmetry of the shot feel unbalanced. Instead of keeping a safe distance from the Sergeant, it dares to advance.

We are sucked in, like rubberneckers at a crash. As the camera and Ermey approach each other, Ermey calls out infractions, “Trim ’em. Toe jam. Pop that blister.” The recruits accept his routine assault stonily. Their faces show nothing. The camera is at Sgt. Hartman’s height—not that of the recruits, who are all atop cheap pedestals.

This creates a visual imbalance of power.

Normally, things that are higher up are seen as dominant. By ignoring this Kubrick adds a layer of discomfort. The scene is already moving in the wrong direction and looks off-kilter. Now it subverts your expectations, as well.

As Ermey closes in on our lead characters—Joker, Pyle, and Cowboy—the camera moves to a position behind their backs. We look between them to see the Sergeant and beyond him the unmoving, unfeeling faces of the other recruits. We see Ermey’s face clearly for the first time, set in a mask of loathing, his cheek twitching with fury. His head is level to the men’s stomachs and he does not look them in the eye. They are not men to him, only lumps of flesh to be molded into Marines. Although they surround him and loom over him, he is the loaded weapon.

Kubrick also squeezes out a few more steps here, prolonging the tension. In the previous shot, Ermey was passing Joker and reaching Pyle. Now he walks past Joker a second time and stops in front of Pyle while we anxiously wait.

Hartman backs up half a step having seen something amiss.

Kubrick now cuts to an insert of what Sergeant Hartman sees, but we’re not looking from his point of view. The camera remains behind the recruits and the meaning here is clear; we are not watching these events unfold through the eyes of the powerful Sergeant. We are not even looking in the place of the recruits, raised up on footlockers. We are lesser, behind, and beneath. We are more than helpless.

The insert is all feet and locker. Two sets of shower sandals, the Sergeant’s polished black shoes, and the bare feet of Private Pyle. Pyle’s footlocker is unlocked, the padlock hanging open. Sergeant Hartman leans down into the frame and we see his arm as he grasps the lock. As he stands the camera tilts up to follow him. His bellowing face is full center in the frame. Behind him, recruits remain frozen, hands outstretched. Although he’s screaming at Pyle, the shot lops Pyle off at the neck; his head not worth including in the shot. It is not important.

Hartman: Jesus H Christ. Private Pyle, why is your footlocker unlocked?

Again we cut. We move to a position down the aisle from Hartman, this time perched just off Cowboy’s chest, as if we’re farther down the line and peering in on the disaster unfolding. Still the Sergeant is looking up at the recruits, specifically Pyle, like an attack dog. Each time he spits out a word he levitates up out of his shoes, as if the height differential is something he can alter with sheer venom.

Hartman: Private Pyle, if there is one thing in this world that I hate, it is an unlocked footlocker! You know that don’t you?

Pyle: Sir, yes, sir!

Hartman: If it wasn’t for dickheads like you, there wouldn’t be any thievery in this world, would there?

Pyle: Sir, no, sir!

Hartman: Get down!

As Pyle steps off his locker and passes in front of the camera, Kubrick again cuts. Now we’re across the aisle from Joker and Cowboy, looking from behind the facing recruits. Again the feeling is that they—the recruits—are witnesses not participants in the spectacle. They can and do ignore the plight of Private Pyle but you, you cannot. You are there looking at his pathetic dough face as he steps down to your level. Although the barracks is filled with people, only three individuals occupy the tier in which the drama unfolds—Sgt. Hartman, Pvt. Pyle, and you.

As Pyle stands in the middle of the aisle, Hartman flips open the offending footlocker. He lifts the top tray and hurls its contents onto the floor in front of Pyle. “Let’s just see if there’s anything missing, shall we?” he barks. He follows by dashing the tray down, too, as if it personally deserves his wrath as well.

Much of the electricity in this scene has to be credited to Lee Ermey. He is a Tesla coil of fury. Each motion, each word spits from him like shock. And what is remarkable is that this man, smaller than Pyle, outnumbered greatly, and behaving like the exponential result of in-bred ferocity so fully controls every atom in the room.

He is a killer. These other men are not. They are just wadded up lumps of chewed bubblegum.

Hartman again turns to the locker and he cannot believe what he sees. Pyle has stolen a jelly donut from the mess hall—something that is expressly forbidden. The Sergeant picks it up between two fingers like a hardened turd and expresses as much disgust. As lacerating as he was before, now is worse.

Sergeant Hartman eviscerates Private Pyle and the camera again jumps in closer. Now we are inside the columns of recruits and stood right beside Vincent D’Onofrio looking past him to Lee Ermey. The Sergeant is yelling at Pyle, but based on the camera position, it is obvious that we are next. If we do not move, maybe we will remain unseen and escape—like Joker whose pale, still form fills the background of this shot. All the recruits, Pyle included, remain frozen. They are frogs caught in the flashlight’s beam. If we don’t move, they think, maybe we will remain unseen and safe.

Sergeant Hartman eviscerates Private Pyle and the camera again jumps in closer. Now we are inside the columns of recruits and stood right beside Vincent D’Onofrio looking past him to Lee Ermey. The Sergeant is yelling at Pyle, but based on the camera position, it is obvious that we are next. If we do not move, maybe we will remain unseen and escape—like Joker whose pale, still form fills the background of this shot. All the recruits, Pyle included, remain frozen. They are frogs caught in the flashlight’s beam. If we don’t move, they think, maybe we will remain unseen and safe.

Hartman: Holy Jesus! What is that? What the fuck is that? WHAT IS THAT, PRIVATE PYLE?

Pyle: Sir, a jelly doughnut, sir!

Hartman: A jelly doughnut?

Pyle: Sir, yes, sir!

Hartman: How did it get here?

Pyle: Sir, I took it from the mess hall, sir!

Hartman: Is chow allowed in the barracks, Private Pyle?

Pyle: Sir, no, sir!

Hartman: Are you allowed to eat jelly doughnuts, Private Pyle?

Pyle: Sir, no, sir!

Hartman: And why not, Private Pyle?

Pyle: Sir, because I’m too heavy, sir!

Hartman: Because you are a disgusting fat body, Private Pyle!

Pyle: Sir, yes, sir!

Hartman: Then why did you try to sneak a jelly doughnut in your footlocker, Private Pyle?

Pyle: Sir, because I was hungry, sir!

Hartman: Because you were hungry.

As Hartman turns to address the rest of the platoon, Kubrick cuts again. Now, finally, we are back where we belong. Where we feel instinctively safe. We are centered in the aisle, exactly as far from Sergeant Hartman as we expect to be. We know that when he starts moving towards us we will back away to keep that protective distance between us. And that’s exactly what happens.

We have remained still and survived. But surviving isn’t so easy in a world of shit. We are not yet killers. We do not have the thousand-yard stare. We will suffer.

The camera slides back and away as Ermey advances, moving with the ghostly footsteps of Stedicam. Although the Sergeant is shouting and in command and Pyle is frozen, it is Pyle who feels centered in the frame. I say ‘feels’ because it is an illusion. Ermey walks along the right side of the aisle and the camera cheats slightly in the same direction. Your brain ignores the far right of the frame, where there is no action, and focuses in on the symmetry created by the two columns of stock-still recruits. Locked between them is Private Pyle and the disarrayed contents of his footlocker. In the true center of the frame—to our right—is Hartman, but we focus on the distant form of Pyle.

Hartman: Private Pyle has dishonored himself and dishonored the platoon. I have tried to help him. But I have failed. I have failed because YOU have not helped me.

Reaching the end of the aisle, Hartman turns and the camera follows him back down, maintaining safe distance. The unmoving recruits continue to avoid reaction. There is no response to the stimulus of pain—particularly the pain of others. We are unfeeling as we watch Hartman walk away from us, closing back in on his victim.

Hartman: YOU people have not given Private Pyle the proper motivation!

That word, “you,” is accentuated in Ermey’s delivery. Repeatedly. And that’s how Kubrick flips the paradigm a second time. Down was up. Now, Pyle’s failure becomes our punishment.

Perhaps we will not survive after all.

The camera hops ahead of Lee Ermey to show us his countenance in a medium tracking shot. We are tighter in than before and more centered on Sergeant Hartman. We have lost our safe distance. We are clearly in his sights. Surprise! You are now the victim. Let me see your war face.

Hartman: So, from now on, whenever Private Pyle fucks up, I will not punish him! I will punish all of YOU! And the way I see it ladies, you owe me for ONE JELLY DOUGHNUT!

As the tirade reaches its crescendo, so Hartman reaches the figure of Pyle. The camera gently cheats up so that Hartman’s face becomes centered in the frame and the somewhat taller D’Onofrio’s head and shoulders fill the left side. The donut hangs before Pyle, clamped in Hartman’s extended fingers like the corpse of a bird.

Another cut. This time the camera is just off the floor, far enough from Private Pyle so that—looking up—his whole body can fit the frame. He stares straight ahead, desperately ignoring both Hartman’s assault and the donut dangling in front of him.

Hartman: NOW GET ON YOUR FACES!

Instantly, the frozen platoon complies. Despite their rigid and uncaring appearance, they have all been viscerally involved in what has been occurring in front of them. This is what it is like when you are only mimicking a thousand-yard stare. You look like you do not care, but that is no more than surface grime. These men are killers-in-training, not killers. Without pause, they are all on their faces and ready to accept punishment for the crimes of the world.

Instantly, the frozen platoon complies. Despite their rigid and uncaring appearance, they have all been viscerally involved in what has been occurring in front of them. This is what it is like when you are only mimicking a thousand-yard stare. You look like you do not care, but that is no more than surface grime. These men are killers-in-training, not killers. Without pause, they are all on their faces and ready to accept punishment for the crimes of the world.

We switch back to our previous camera position beside Private Pyle. Hartman shoves the pastry into Pyle’s face. Again we are right there with him, expecting to be next in line. We are not doing push-ups now because we, like Pyle, are the burden that others must bear. We are both the criminal and victim. The killer and the killed. That is the duality of man.

Hartman: Open your mouth! They’re payin’ for it; YOU eat it! Ready! Exercise!

The scene ends with two shots. The first is a close up of Vincent D’Onofrio eating the donut. Finally, after all this time, we see his face clearly. Go back and look. Throughout the scene, we have never focused on him as the main subject; he has always been ancillary. He has not been a man, or person, or anything but an obstacle. Until his world merged with ours.

The scene ends with two shots. The first is a close up of Vincent D’Onofrio eating the donut. Finally, after all this time, we see his face clearly. Go back and look. Throughout the scene, we have never focused on him as the main subject; he has always been ancillary. He has not been a man, or person, or anything but an obstacle. Until his world merged with ours.

Now he is important because his failure is our punishment. Watch him eat the jelly donut. Watch him try to keep his expression from revealing just how destroyed he is.

Then we cut back to the position off the floor in front of Pyle. This time, Sergeant Hartman is not present. Instead, Pyle is flanked by two lines of recruits, on their faces, doing rhythmic push-ups as they chant, “One, two, three, four, I love the Marine Corps.” Pyle is stood in the center, like the class dunce, if the class were armed and training to kill. His possessions surround his feet, just part of the shit that forms the walls of his world. It is the same shit that comprises our world now.

Pyle struggles to swallow what he has unwittingly wrought. It is nothing less than his own death.

Skritch, skritch, skritch go the mind bugs. Feel them crawl and chew and defecate inside your skull. Nope. Full Metal Jacket isn’t about war. It’s about much more than that. Life and death and our feeble and misguided control over each.

Hartman: If you ladies leave my island, if you survive recruit training, you will be a weapon. You will be a minister of death praying for war. But until that day you are pukes. You are the lowest form of life on Earth. You are not even human fucking beings. You are nothing but unorganized grabastic pieces of amphibian shit. Because I am hard you will not like me, but the more you hate me the more you will learn. I am hard but I am fair.

This is a great post.

But what does ‘the walls bleach to dun’ mean?

Thanks Mash.

Bleach to dun; lose their color in transition to pale tan.

Hi evil genius

good post, but if you think that the monolithe is a “happy accident”, you are wrong.

Read my postings at

http://www.andrewgough.co.uk/forum/viewtopic.php?f=39&t=4345&p=127668#p127668

Kubrick gives a hint, that the monolithe is the burning WTC !

regards Hans Peper

Hans.

You have some very interesting ideas. Of course, meaning is where you find it — that’s what makes film such a powerful medium; there’s a ton of room to place and find meaning, personal or intentional.

There are even more places to find meaning in your own skull, however. Humans have evolved over millennia as pattern-recognizing machines. I believe you must be a bit more evolved than the rest of us, and that includes Stanley Kubrick.

Regards,

EG

I loved your analysis of the jelly doughnut scene. Would you allow me to use the doughnut segment of your essay on my podcast? Thank you in advance, even if you say no.

Sure thing. You go right ahead. It would be swell if you mentioned the site on your podcast but also, thanks in advance even if you don’t.