The trouble with Irish independence is the same trouble with independence sought by any peoples throughout history: you spend ten, twenty, a hundred, five hundred years murdering your oppressors, the people you’re oppressing, each other, and anyone else handy until, reaching a moment of relative peace, you scratch your scraggly rebel beard and ask yourself, was it all worth it? Killing all those people? For all that time? Maybe you think it was. Maybe you got your independence in the end. Or maybe you wonder whether anything is worth all of that killing. On the other side, waxing your well-kept imperialist moustache, you think the same thing, more or less: was it worth all those people dying and being killed in an ultimately failed attempt to keep what you believed was yours? If the attempt didn’t fail, would that have made a difference? Is anything worth all of that violent death? You’d think on it longer, but that’s when the moment of peace passes and you’re back to killing anything that moves, righteously, no matter which side you’re on.

Which is to say, this week’s double feature is a barrel of laughs! And by “laughs” I mean the copious tears you’re going to cry watching it. You’ll be able to fill a barrel with those tears. Into which tear-filled barrel you may then put in any number of fish. And shoot them.

You’re up on your Irish history, I assume? In brief, and I mean one-paragraph-brief, things got sticky between the British and the Scottish and the Irish back in the 1600s. Many rebellions later, in 1801, Ireland was incorporated into the UK. The unionists were generally Protestant and supported the British. The nationalists were generally Catholic and wanted an independent Ireland. Problems festered. Mid-WWI, Irish republicans staged the Easter Rising, and declared Ireland independent. This led to the Irish War of Independence of 1919-1921, known at the time as the Troubles, not to be confused with the later Troubles starting in the ‘60s. We’ll be getting to them.

We begin this week’s double feature in 1920, smack in the middle of the War of Independence:

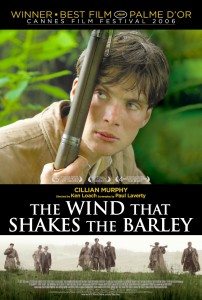

The Wind That Shakes The Barley (2006)

A naturalistic, heartbreaking story focused on two Irish brothers involved with the Irish Republican Army (IRA), at the time a guerilla army opposed to the British, AKA the Black and Tans. Cillian Murphy stars as Damien, a young doctor about to head off to London to practice medicine, and Pádraic Delaney is his brother Teddy, a commander of an IRA brigade. Witnessing violent abuse at the hands of the British, Damien decides to stay behind and join his friends and brother in the fight.

I’m going to go ahead and say this is director Ken Loach’s best movie, even without the benefit of having seen all the others. Sometimes you have to take a stand. It’s certainly his most popular movie. It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in ’06, and for a number of years held the record as the highest grossing independently produced Irish movie ever.

Loach’s style is very laid-back and realistic, to the point where you tend to think the actors are improvising their lines. They’re not. Loach directs from tightly written scripts, this one by frequent collaborator Paul Laverty. Loach’s movies look very much like the independents they are, in the sense that there’s no Hollywood flash or sentiment or overwrought bullshit getting in the way of what in this case is a very powerful story.

Also unlike Hollywood war stories, the question of who’s good and who’s bad becomes very murky in The Wind That Shakes The Barley, just as it did in the actual circumstances it depicts. As the war continues, a friend of Damien’s is found to have been supplying information to the British. What to do with this traitor? Kill him? Will Damien have to do it? If so, how will that change who he is?

In ’21, the Anglo-Irish Treaty is signed, granting Ireland status as a British dominion. This is good enough for many of the Irish. For many others, it is not, and the fight continues. Damien and Teddy find themselves on opposite sides of the issue. Teddy, who got Damien into the fight in the first place, sees it as a way to peace and future gains. Damien, having found the rebel inside himself, sees it as an unacceptable cop-out.

Loach is exploring the difference between a nationalistic revolution as opposed to a social one. Is simply changing the flag and leaving everything else the same enough? Or is the revolution a means to make massive changes to the social order? Is it worth settling for a small victory now in the hopes of achieving more in the future? Or is it all or nothing?

Teddy and Damien come to a point where political disagreement is indistinguishable from the personal. This is what the movie builds to. The ending is predictably devastating.

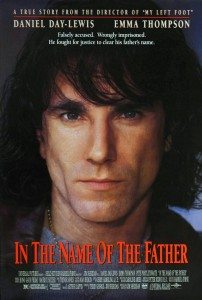

In The Name of The Father (1993)

The Anglo-Irish treaty left Ireland as a British Dominion. Northern Ireland opted to remain a part of the UK. Nationalists considered this partitioning of Ireland illegal. The IRA remained alive if marginalized and continued to demand full Irish independence.

And so things went until the later ‘60s, when the new Troubles began in earnest. Things get rather involved and murky here. Riots, civil rights marches, the IRA back in full force, the Republic of Ireland in support, the British sending in troops to aid Northern Ireland, Protestants against Catholics, bombings, etc. and so on and on and on.

In The Name of The Father takes place in the midst of this. It’s based on the true story of the Guildford Four, four people wrongly accused and convicted of blowing up a pub and killing four British soldiers and a civilian in ’74. (Say, that’s a lot of fours. Apropos of nothing. Carry on…)

Daniel Day Lewis, long before he was Lincoln, plays Gerry Conlon, something of an Irish hippie punk, let’s say, who’s sent off from Belfast to London by his parents in the hopes of keeping him out of trouble, and more to the point, out of the Troubles.

As luck would have it, the bad sort of luck, Gerry happens to be near the Guildford Pub when the IRA blows it up. Unaware he could be suspected of such a thing, he goes home to Belfast where the British Army raids his house and arrests him.

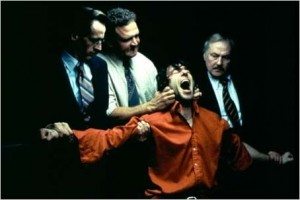

Gerry and three others, after their torture results in guilty pleas, are eventually convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Or so. Long sentences, anyway. Worse still, Gerry’s father, Guiseppe (Pete Postlethwaite), is arrested for aiding the bombers and winds up in prison with his son.

Now this is exactly the type of movie that so often manipulates you with all the subtlety of a 2×4 to the face with cheap, weepy scenes and saccharine music to make sure you’re FEELING just how awful and sad and moving it all is (think everything by Oliver Stone). Fortunately, this is that rare movie whose director, Jim Sheridan (who wrote it with Terry George), understands that simply by telling the story, the emotional intensity is going to take care of itself. And it does. By the time this ends, you’ll be on your feet in tears pumping your fists in the name of righteousness. Granted, you’ll probably have to be doing this to the strains of a U2 song, but what the hell, it’s an Irish movie, we can let that slide (with apologies to any U2 fans out there. There aren’t many of you, right? Not really a popular band? Anyway…)

Much of the movie takes place in the joint, where Gerry has to deal with his wrongful imprisonment, and with his ailing father, wrongly locked up with him. You know there are going to be some father/son issues that need working out. I seem also to recall a memorable acid trip in there somewhere.

Oh, and doesn’t the real IRA perpetrator of the bombing end up in the same prison too? He does. Conflict ensues.

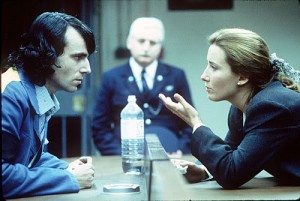

Meanwhile, Emma Thompson plays the lawyer who doggedly pursues the case, discovering all the evidence the police sat on during the original trial. Suffice to say, when the evidence comes to light, justice is served.

Put these two movies together, and you wind up with a look at close to a century of continued conflict, a conflict begun some three hundred years earlier (or more?), and that while relatively calm now, isn’t necessarily over by any means.

So like I said. A barrel of laughs. And fish! And you, shooting them.

Man. I remember absolutely hating Wind That Shakes the Barley when it came out. I have no idea why, though. But I sure hated it. With the passion of ten-thousand bottles of SunnyD.

There’s a really good pre-insanity Sinéad O’Connor song in In the Name of the Father. I’ve got it squirreled away somewhere. Ah. Here it is. Thief of My Heart. I believe (sorry) it was written by Bono(bo).

Did you now, laddie? Well, who knows. I remember liking it quite a bit when it came out. It’s been since then that I saw it.

And, just to complete the troika, I found it bland and predictable, though lovely to look at.

On the other hand, I thought that Paul Greengrass’ Bloody Sunday, about the massacre of 13 Irish civilians by British Para’s in 1972 was fantastic and emotionally devastating, so I’d say everyone should watch that as well …