One thing I love about old movies is the window they open on the past. It doesn’t matter when they’re set, be they westerns, science fiction, or contemporary. It doesn’t matter if they’re good or bad. Every movie reflects the time it was made in, every movie shows you how people behaved, what they believed, what they imagined, how they dressed, how they spoke, what was proper to discuss, what was shocking. Taking a step back, every movie shows you how far advanced the technology of filmmaking had become. How is it shot? How is it edited? Is there a new technique being shown off? Is that new technique a brilliant breakthrough? Or a bunch of hooey?

A great line in a Tom Petty song goes: “The future ain’t what it used to be.” Nope, not a bit. Even a movie as great and lasting and beautiful as 2001 is in ways dated. Check out the furniture in the space station, those awesome pink chairs. They’re futuristic in a way unique to the late ‘60s. Sci-fi rarely has much to say about whatever future awaits us. What it tells us is all about the present. Thus the future of the past was a lot different than the future of today.

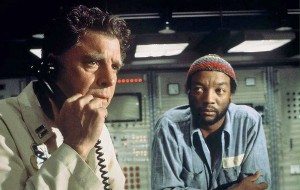

There’s a funny moment early on in the ’77 political thriller Twilight’s Last Gleaming, directed by Robert Aldrich (of Kiss Me Deadly and The Dirty Dozen fame, among others), where Burt Lancaster, playing General Dell, breaks into a Montana nuclear missile silo with his compatriots, two escaped felons played by Paul Winfield and Burt Young, and the camera does a long, slow pan across the computerized control panel. It’s shot in a way that says, “Wowsers! Look at how complex and big and shiny and technologically advanced that is!” Only by today’s standards it looks like a mildly diverting toy you’d give a six year old.

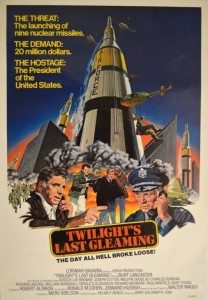

If you’ve never heard of Twilight’s Last Gleaming, don’t worry, you’re not alone. It bombed when it opened, it never made it to videocassette, and was released on DVD for the first time last year. It’s one of those lost movies that today’s critics praise as being overlooked gems. In this case, there’s a reason Gleaming was lost: it’s almost, but not quite, entirely awful. It’s slow and ponderous and outrageously long at two and a half hours, it’s by turns absurd, overwrought, sentimental, cynical, and unbelievable, its look is bland and colorless, the cinematography resembles a badly lit spread in a mid-‘70s issue of Popular Mechanics, the editing features a wild split-screen technique that divides the screen in half vertically or horizontally, or horizontally with the top section cut in half vertically (for a three screen effect) or cut fully both ways for a four screen effect (which didn’t Mike Figgis do that in Timecode? Looks like Aldrich beat to the punch by 23 years, Figgis), and in the end you learn nothing you didn’t already know about the shady, amoral machinations of your government. Which applies not just to us now, but to anyone with half a brain alive in ’77.

It’s set in the all-too-possible future of ’81. Colonel Dell, who we learn was wrongly imprisoned by the army for murder, has escaped with Powell (Winfield) and Garvas (Young) and another guy they shoot for being a hothead. Through a long and boring series of ridiculously amateurish tactics, he and his men gain control of a missile silo, and lock themselves in tight behind a door as big as the one in Tron. They have the power to launch nine nukes, and no one can stop them.

What are Dell’s demands? First, to talk to the President. The President is played by a frumpled and semi-befuddled Charles Durning, a good guy in charge in bad times. Dell wants the President to read aloud to the American people a certain secret military document which, we later learn, explains in blunt language the real reason for the Vietnam War: to show the Soviets that we’re a bunch of crazy bastards willing to suffer anything to get our way. The war in which millions died and were wounded, cries an outraged President to his advisors? How could we have?!

Many long scenes around a table in the oval office later, we learn that yes, our government is run by men who, handcuffed by political realities, must lie to the American people and behave like bastards to do the right thing, which right thing is to maintain power. The President lies to Dell, says they’ll agree to the demands, then sends in a crack platoon of men to place a small nuclear device in the silo and blow it up.

Watching this long sequence unfold is like watching an early ’80 video on how to properly caulk bathroom tile. It’s bizarrely bad. The split screen effect is used in full force. We see Dell, we see the President, we see the men sneaking into the silo, we see video feeds from the helicopters hovering above the silo’s security cameras, we see the feeds from those cameras, and at no time do we have any clue who’s looking at what.

The plan fails when the army guys are spotted by Dell and Powell. Outraged they simultaneously turn their launch keys and nine nukes rise from their silos. WWIII is coming! With seconds to spare, the President calls off his men.

After all that, the President tells Dell he’ll accede to their specific demands: he’ll deliver himself in Air Force One along with ten million dollars to the silo. Dell and his one remaining partner, Powell, will use the President as a human shield to get themselves into the plane, and off they’ll go, after which the President will read the document on TV. Because the President realizes that the truth must be told. He agrees with Dell, by gosh, because Vietnam was a fraud, and we all have a right to know it!

The President asks his Secretary of Defense (Melvyn Douglas) to promise to read it himself should the President die. He promises.

What’s historically interesting about all of this are a number of things. First of all, the general air of cynicism about the government stemming from anger at Vietnam. Compare that to Zero Dark Thirty or Argo, which is even set in the same era. Movies today dare not so much as question the government, let alone criticize it. In Argo, it’s celebrated. In the ‘70s we had Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter, The Parallax View, etc., movies that actually had some balls and a point of view.

As the finale approaches, Powell gives the best speech of the movie to Dell, telling him he’s an idiot to think this plan will work, to think those running the show would ever read that document. The President as human shield? The President is expendable, says Powell. They’ll shoot through him to get at us. There’s no way they’ll let us out of here alive. It’s a great, outraged speech, and it rings completely true, even to Dell, who decides to launch the nukes. But Powell won’t turn the other key. He’s not going to blow up the world out of pique. What can Dell do? Shoot him? He has to go through with his own plan and hope for the best. Dell isn’t exactly a hero in this thing. He’s unhinged.

The amount of swearing in the movie is interesting too. There’s a lot, and it’s all delivered as if every curse is subversive. It’s kind of strange. It’s like the movie is daring you to hear these “real” words, that yes, even the President of the United States says “fuck” a lot. Which suggests that in ’77 these words still had some transgressive power lacking today.

The cast is full of still more famous faces, including Joseph Cotten, Richard Widmark, and John Ratzenberger (and notably not a single woman), just like a ‘70s disaster movie. Watching Twilight’s Last Gleaming I was reminded more of The Towering Inferno, The Poseiden Adventure, and Airport ’75 than other political thrillers of the era.

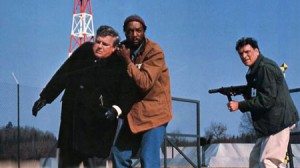

The only thing that kept me watching to the end was curiosity: how cynical would it be? Would Dell actually launch a missile? It doesn’t go that far. The President arrives, Dell and Powell lead him up to the surface and toward Air Force One. Snipers are in place, waiting for the order to fire. But the men keep turning in circles; there’s no clear shot. They’re given the order to shoot anyway. They fire a curiously epic volley of shots (no single kill shot from a trained sniper?), and sure enough all three men keel over. As the President bleeds out, the SecDef comes to his side. The President asks him if he’ll keep his promise—and dies. The SecDef, saying nothing, revealing nothing, walks away as the camera rises up and away. The end.

Acceptably cynical, I’d say, and the norm for the era. Fuck the government! the movie cries out. They won’t tell us shit!

I hope I haven’t made this movie sound too interesting, because really the last thing you should do is watch it. To be honest, I spent the middle hour working a crossword. Not a good sign. Still and all, I’m glad it’s out there. For the view they give of their time, even bad movies are valuable, the more so the more they age.

It still sounds like the best of the Twilight movies. When does Lancaster rip off his shirt and become a hunky werewolf? I don’t know about you but I’m on Team Burt Young.

I like where you’re going with this. If they remade the movie as a Twilight series spin-off, we’d have pure gold on our hands.

I think you judge harshly.The film stems from a time when audiences had a thing called attention span and so a drama could develop altho I do agree about the split screen and the poor lighting