You are the monster. You are the god. You are the destroyer, the creator, the ripping skein of life torn free and thrashing wild. You are the wind that cleanses and burns and you are only a boy.

And not even the most powerful one. That would be Akira.

Akira has already destroyed your world once and now he’s returned. Because you called.

Akira has already destroyed your world once and now he’s returned. Because you called.

The first time I saw Katsuhiro Otomo’s anime masterpiece Akira, I was in college. I am not exaggerating in the slightest when I say it tore my brain into tiny pieces. Everything about it—the kinetic, visceral animation; the deeply cinematic staging; the insidious score; the imagery that burned shadows into the back of my skull—left me dizzy.

I had almost no idea what had actually happened in the story, though, or why.

It was something complex about a teenager who discovers incredible power locked within him. He loses control. Neo-Tokyo, the setting for the tale, roils around him with motorcycle gang warfare, rebellion, religion, and rebirth. The world crumbles and re-compacts so that its myriad cracks fuse. But, still, you know those cracks remain. You can sense them everywhere.

Through the years I have watched Akira over and over again. I thought I understood its glorious but suggestively sketched plot. I wasn’t wrong, but I wasn’t right until I read the manga.

[Press play for mind control]

Creation

Back in 1982, writer and penciler Kasushiro Otomo began writing a serialized graphic novel, published in weekly installments in Japan’s Young Magazine. This was the start of Akira. By the time he finished, it was 1990 and he had produced over 2,000 pages.

Before the manga of Akira was finished, however, Otomo began working on an animated version of the story. The film was released in Japan in 1989, later in the West. The manga and the film are interlinked but not the same, like conjoined twins, developing together but growing apart. Both are adaptations of the other.

Before the manga of Akira was finished, however, Otomo began working on an animated version of the story. The film was released in Japan in 1989, later in the West. The manga and the film are interlinked but not the same, like conjoined twins, developing together but growing apart. Both are adaptations of the other.

The film version is vastly condensed, omitting entire plots that spiral through the manga, cutting and combining major characters, and leaving themes and meaning to be inferred or even just sensed. Many of these omissions are hard losses. Lady Miyako, for example, appears only briefly in the film. Her seconds of peripheral screen time condense hundreds of pages of introspection on religion and religious warfare.

Neo-Tokyo also suffers as a character. Things that happen to it in the manga—nasty, horrible things—don’t happen in the film. Its cycle of rebirth disappears and so it cannot play counterpoint to the stories that do get told.

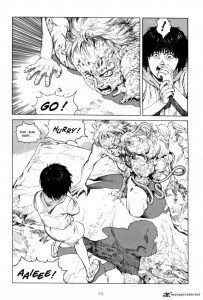

That’s some of how the film is different from the manga. The two are the same in other remarkable ways, though. For one, the plummeting, addictive sense of momentum holds true. Otomo’s drawings capture physicality in a way that shoves you around. His clever staging of panels makes it almost impossible to stop reading the thing once you’ve begun; it is as if you’re falling into the book (now available as six graphic novels).

While I’m not a connoisseur of manga, I do know a thing or two about comic books, and I’ve never read anything else like Akira. It’s like Frank Miller took 2,000 pages to adapt an Alan Moore story.

The grand overarching tale also remains the same. You get the story of Tetsuo Shima, orphan and weakling, who survives under the wing of his tougher friend, Capsule motorcycle gang leader Shotoro Kaneda. These young men live in Neo-Tokyo, a future city rebuilt after the cataclysm of World War III—which began on December 6, 1992.

In this reborn world, there are strange, secret post-humans; eternal children developed by an army that does not fully understand or control them. As politics and power struggles rip the city apart, Tetsuo collides with one of these ‘espers’ and his own immense potential is unleashed.

In this reborn world, there are strange, secret post-humans; eternal children developed by an army that does not fully understand or control them. As politics and power struggles rip the city apart, Tetsuo collides with one of these ‘espers’ and his own immense potential is unleashed.

Conflict

At the heart of both the manga and the film, Tetsuo and Kaneda spar. These old friends become enemies and the story maps their prolonged duel, interwoven with other aims, other parties, and other battles. It is a conflict between established blind strength and ravenous need. It is replayed through numerous variations, like a musical theme, avoiding platitudes and easy answers.

Many will tell you that the hero of the story is Kaneda—that he is the protagonist—and that Tetsuo is the villain. This is not true.

During all the times I’ve watched Akira, I never once wanted to be Kaneda. You won’t either (although you may covet his motorcycle or laser rifle).

During all the times I’ve watched Akira, I never once wanted to be Kaneda. You won’t either (although you may covet his motorcycle or laser rifle).

Kaneda—naive, rash, and egotistical—plays the part of the savior, but it’s an illusion. He never understands what is happening around him. He goes through the motions because that is what is expected of him. He is just an actor on too big a stage. A pawn, not a player.

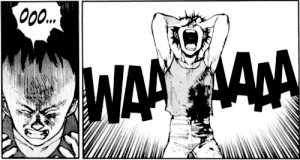

The real protagonist of Akira is Tetsuo. Tetsuo the monster. Tetsuo the destroyer. Tetsuo the god. And you will not want to be him, either.

Akira is a disaster film from the point of view of the disaster. That is pretty hardcore.

Now, the story is vastly chaotic, as befits an eight-year endeavor. If you skip reading the manga, you will only ever be brushing against the surface of what Otomo has wrought. For me, for years, that was more than enough. If you do find that the film gets under your skin, however, the manga is definitely worth the investment. I read all 2,000 pages in under a week.

Now, the story is vastly chaotic, as befits an eight-year endeavor. If you skip reading the manga, you will only ever be brushing against the surface of what Otomo has wrought. For me, for years, that was more than enough. If you do find that the film gets under your skin, however, the manga is definitely worth the investment. I read all 2,000 pages in under a week.

You might also wonder who the Akira of the title is. Too bad; I’m not going to get into it. His identity is one of the core mysteries of the story. He is, thematically, also central. This is communicated through repetitive visual motifs.

Neo-Tokyo is in for quite a change! This city is already saturated. It’s become an over-ripe fruit that’s begun to stink. But there’s a new seed germinating inside. All we have to do is wait for the wind to blow and the fruit will fall into our hands. Wait for the wind called Akira!

Dissolution, Fusion, Singularity

I don’t want to give you the impression that in order to watch and enjoy Akira you need to keep your smart pants on. Remember: the first time I watched this film I was more or less completely befuddled by it and I loved it immensely. Like any serious work of art, however, you can peel back layers of text and imagery to find truth.

In Akira, you will notice a few images repeating. Crumbling dissolution squares off against enveloping fusion. This cycle is seen in everything from fracturing pavement, to swallowing pink smoke, to infinitely replicating flesh. Solid and necessary crumbles away. New and ravenous envelops. It is the old war between Apollo and Dionysus; chaos and order; yin and yang; government and rebellion; Kaneda and Tetsuo.

In Akira, you will notice a few images repeating. Crumbling dissolution squares off against enveloping fusion. This cycle is seen in everything from fracturing pavement, to swallowing pink smoke, to infinitely replicating flesh. Solid and necessary crumbles away. New and ravenous envelops. It is the old war between Apollo and Dionysus; chaos and order; yin and yang; government and rebellion; Kaneda and Tetsuo.

Akira suggests there is a final stage to this cycle, one that seems—in appearance and in effect—to be nuclear. This is a Japanese story after all, and a monster movie, and nothing represents both potential and destructive force like an atomic-style blast.

Akira suggests there is a final stage to this cycle, one that seems—in appearance and in effect—to be nuclear. This is a Japanese story after all, and a monster movie, and nothing represents both potential and destructive force like an atomic-style blast.

In this film, the third major symbol combines the first two. Everything is torn apart and smashed together in order to be overcome by the spreading singularity. This is depicted as a growing orb and the growing orb is, in all ways, Akira.

This time, that energy will be ours

Writing about Akira, I feel a bit like one of its characters, ranting on the street corner, mobilizing troops to call forth the impending apocalypse. But I also feel like a kid at the candy store because when you’re watching this film, everywhere you look is something you want to ingest.

Even if you ignore all the intricate, half-explained thematic stuff, you still get a kick-ass sci-fi adventure.

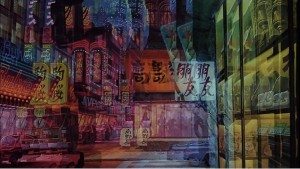

Visually, Akira takes the panels of the manga as a starting point, but then it layers in deeply cinematic effects. Otomo uses shallow focus to mimic three-dimensionality, slo-motion, and as you see here, lighting effects like trails.

Visually, Akira takes the panels of the manga as a starting point, but then it layers in deeply cinematic effects. Otomo uses shallow focus to mimic three-dimensionality, slo-motion, and as you see here, lighting effects like trails.

This is hand-drawn stuff, not the computer generated material you get from today’s animation powerhouses. In that way, Akira looks more like a classic Disney film.

Although not, of course, in terms of subject matter. Akira is undeniably adult. This is a story full of violence, death, and horror. Kaneda and the rest of the Capsules are not fine, young, upstanding men. You should not show Akira to children unless you want them to be terrified of their teddy bears for the rest of their lives. Or kill everyone with their psycho-kinetic powers.

There is a depth to this animation that trumps most other productions. Dialogue was pre-recorded so characters could move their mouths in synch. Backgrounds look rich in immersive detail. Otomo elevated the standards of the genre with these and other innovations. It cost and he paid.

The other element that makes Akira so compelling is its score. Hopefully you’re listening to some of it now through the audio players embedded in this post. (The tracks are Kaneda, Battle Against the Clowns, and the second half of Tetsuo.)

Composed and conducted by Shoji Yamashiro, this music sounds like something Ennio Morricone might have dreamt up while chugging ayahuasca. Powerful choral chants overlay odd instrumentation—lots of xylophone, synth, and percussion. Some of it sounds like religious music. Some of it is borderline cacophonous. I find it all insidious and transportive.

The soundtrack comes in two versions, if you wish to pretend you are about to destroy Neo-Tokyo at home. The original version is the rerecorded, expanded score split into tracks that more or less follow the sequence of the film. Another version is available that lifts the audio directly from the film and cuts in sound bytes of the characters.

Speaking of audio, should you be settling in for a screening of Akira, don’t be a jackass: listen to it with the original Japanese audio track and subtitles. This is a very Japanese story. You want to hear the Japanese inflection and emotion. Reading won’t kill you and you’ll probably fail to understand everything the first time through anyway.

If you only ever see one anime film, Akira should be it. It is as thematically robust a film as Blade Runner, as emotionally evocative as 2001, and as viscerally engaging as Children of Men. It is a film I love and have seen a dozen times or more.

If you only ever see one anime film, Akira should be it. It is as thematically robust a film as Blade Runner, as emotionally evocative as 2001, and as viscerally engaging as Children of Men. It is a film I love and have seen a dozen times or more.

Watching Akira will change you. It will break you down, fuse the pieces, and absorb you whole.

Then you’ll want to watch it again.

Well, you’ve made me want to check out Akira again. I only ever saw it once, in high school. I remember exactly nothing, aside from me and Shindler and Fuzzy laughing at inappropriate moments.

You were probably high, which isn’t a bad way to watch Akira.

It has just come to my attention that this is Stand By For Mind Control’s 200th post. To celebrate, we will be jumping out of a cake. I just need to perfect my intra-cake teleportation device. Which is going to be AWESOME.

Fantastic writing, the music and gifs really enhance the article, thanks!

Thanks, Denis! Welcome to SB4MC. Hope to keep seeing your around.

Wow.

I always had a sense of Japanese anime as an iceberg on the edge of the horizon, but in some direction that I wasn’t going–a massive entity of whose scope and depth I was totally ignorant, and content to remain so because I already knew I liked Mozart and Bach and Tchaikovsky and Queen and Audioslave and I didn’t want to have to wander over seas of Wagner and Chopin just to get to Stravinsky. (To mix metaphors thoroughly. I blame your clips of Yamashiro’s shimmering score.)

Now it seems I’ve mistaken the matter entirely. The small crag on the horizon is not an iceberg but a distant shore, one which extends far past my path over the seas, on which I must land before going elsewhere, a la Columbus bumping into a continent on his way to India. And because I insisted on reading ‘Moby Dick’ instead of the assigned ‘Bartleby the Scrivener’ in high school (because the former is Melville’s masterpiece, and why bother with lesser works when you could be reading the best thing someone has ever written?), chances are high that I’ll land at ‘Akira’.

It sounds like choosing to land on a peninsula of Himalayan mountains so that one is forced to scale the equivalent of Everest to reach the interior of the continent. Fortunately, I love climbing.

Thank you for sharing this with us, Evil Genius. It’s good to hear your voice again. (And congratulations. Sorry I missed the cake-based part of your performance, especially since it was probably an ‘Akira’-themed cake; the visual effect was probably well worth the price of airfare.)

I’m not sure how I failed to notice the date on this before posting, but everything in the last paragraph still holds true. Off to search for more recent words from you.

Always nice to hear from you, and glad you found this post — and Akira. I don’t know that any other anime has meant nearly as much to me, so please do give it a shot. Not that I’m an anime junkie, but: there’s some good stuff in there.

Hello, again…

Glad to see we share a love for Akira as well. Love the review, all the things that you point out are what attracted me to this movie when I first saw it when I was a teenager. I too did not understand much of what was happening but it all looked so cool, I didn’t care lol… Although the comics do help explain things more.

Yes! I was really glad after I read the comics. I’m unsure of what to think about the Taika Waititi remake… I loved his Hunt for the Wilderpeople but Akira is a beast and seems tonally so different from his Kiwi-comic style.

Hi again, I wanted to thank you for putting up some of the music from this movie. That was the other thing about Akira that stood out for me,(and still does) the music is almost as cool as the Animation.

I’d also love to see your take on some other classic Anime movies like Akira.

Hi John. Yeah. I put this score on all the time. It’s crazy to work to. I’m not the biggest Anime fan — I’ve seen a bunch of the big titles but none have moved me like Akira has. Although Into the Spider-Verse was pretty great (and not Anime). Your Name was solid. Others look good or have good ideas but haven’t yet made me thrilled. What are your favorites?

Akira is the main one that got me into anime, but there are few others I can think of that may be worth a look. Ninja Scroll is a good one and Vampire Hunter D is another that is worth mentioning. Not sure if you’ve seen any of those.

I haven’t. I’ll add them to the list…

Cool :) Akira will always be the movie that really sparked my interest in other anime. I recently got an opportunity to see it in the theater, the Japanese version, it was pretty intense and worth seeing.Up to that point had only seen it at home.