I realize that I am a little late to the party. That everyone’s already left for spring break, seen Spring Breakers, gotten mostly naked, highly intoxicated, incarcerated, penetrated, and otherwise violated.

And reportedly loved every minute of it until they couldn’t stand another.

And reportedly loved every minute of it until they couldn’t stand another.

Well I finally saw Harmony Korine’s latest exploitation/art-house/pedophobic production last night. It was late in the evening. I had just watched Rebelle (War Witch) and wasn’t sure I had another film in me. I feared I’d fall asleep on one of the New Parkway’s couches before Spring Breakers started.

My fears were fully unfounded. From its farcical MTV über-party beginnings to its corpse-strewn end, I was awake. Very awake.

I pretty much loved Spring Breakers—and not just because it exposed more boobs than Julian Assange.

The members of the lascivious so-called ‘youth market’ who settle in for some skin might just leave its darkened room reasonably satisfied, if a bit bemused, too. Only years later, when the haze of adolescence wanes, they’ll pick their heads up and think, “Whoa. My mind was fucked and I never realized.”

Surprise! This is not actually a scene from the film. This is a scene from life. Actual people living actual lives with no consequences whatsoever.

Which is exactly what Spring Breakers is about. It is about the nihilistic, sociopathic, escapism of youth. And not just the youth of today, but youth in general, including the one you experienced.

The film basically chronicles the descent of four insipid college girls into the spun-sugar hell of spring break. Their journey is awesome to observe, using the word’s original meaning. It is a neon pink, booze-soaked bullet to the head, if that head is smothered in bare breasts.

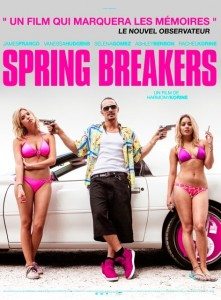

Meet your lead actresses: Harmony Korine, Vanessa Hudgens, Selena Gomez, Ashley Benson, and their pee. Spring break forever!

These four average if attractive young ladies (Selena Gomez, Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Benson, Rachel Korine) simply must step outside of their dull, privileged lives. Three of them commit a robbery, astounding both for its brazenness and for its ease of accomplishment. The proceeds of their crime funds a bus trip to St. Petersburg, Florida, which is drowning in underage, under clothed, absolutely unaware kids committed to full-fledged bacchanalia. As the young ladies’ escapist dream calcifies into crusty reality, the girls pack themselves, one by one, back onto the bus home to boredom. They try to escape their escape.

Small problem though. As Buckaroo Banzai noted, “No matter where you go, there you are.” The bus window may divide a penitent from the wild, wooly world, but it won’t cleave her from herself. She’s going home with scars.

Who are Korine’s stand-ins for blossoming flower of today’s youth? I couldn’t reliably tell these mademoiselles apart, honestly. There was the frankly named Faith (Selena Gomez) whose prayer circle stained glass view of heaven looked mostly indistinguishable from a candy rave. Then there was the other one, who went home second, and the other two, who stayed to vent their fertility with James Franco’s grilled, tatted, hedonistic, man-child drug dealer—known as Alien.

His licence plate read “BALLR” and I’m pretty sure he meant it.

But plot be damned. Spring Breakers isn’t a film about story. It’s a film in which events wash over the audience and the characters like waves. Things happen, and then they happen again, and then they really happen, and then they ebb out, pulling back the sand in which we’ve buried our heads. The effect isn’t disorienting; it’s mesmerizing. Will the kids who go see this film high and horny even notice? Likely not—at least not yet. But that doesn’t keep the meaning from their view, slipping suggestions into their malleable neural pathways. The world is out there and, like it or not, you’re already deep in it.

As we watch, the spring break sold in glossy music videos, in Girls Gone Wild porn, in exploitation comedies like Hardbodies and Screwballs paws its way forcefully onto the screen. There is no lack of nudity in Spring Breakers. From its first few moments, you’d be hard pressed to count the boobs, even knowing they frequently come in pairs. They are attractive, multicultural breasts freed from bikini tops to accept anointing with beer sprayed enthusiastically from well wanked bottles held at groin level by muscled, sweaty, panting boys.

That, it’s fair to say, is not so subtle.

And it’s also not so subtly suggested that this is exactly what our heroines want—even the inhibited Faith. They want hunky men to desire their nubile bodies. They are willing to resort to violence to get it. It is a way to step outside of themselves. Perhaps to be adult, as they perceive it.

When they arrive in St. Petes, everything is just as they dreamed. Magical colors melt a landscape of sun, sand, and sex. But as anyone who has partied hard knows—meaning anyone older than most everyone who appears in this film—beer dries sticky, sun exacerbates alcohol-induced dehydration, and wonton flirting isn’t excellent at establishing personal boundaries. Spring break forever—an ironic mantra of the film—isn’t practical, desirable, or even fun. Alien learns this, slowly. And how can you not be smarter than a guy named Alien?

Korine’s film isn’t heavy-handed. If anything, it errs on the side of the exploitative, keeping you distracted. As you sit agape, though, the tale gradually shifts in intent. It changes color in drips, like a fellated rocket pop. The party becomes progressively less idealized. A woman passes out next to a filthy toilet. Cocaine snorted off a topless girl’s tits seems less of a jolly good romp than rap videos imply. The cops come. The quartet ends up in the cooler, still wearing only bikinis. Spring break forever?

And so enters Alien, with plastic wrapped bricks of drugs, a wall of weaponry, Scarface on endless repeat, and a gangster feud. The girls begin to fold. At the strip club, the bodies aren’t young and hot and shining with suntan lotion. They are mature and real. The party is now populated by rough-looking men marked by the streets, not dreamboat college boys on holiday. The identical twins who shadow Alien share everything, including their sex partners, simultaneously, in exactly as graphic a way as you’re trying not to picture. Is this still the schoolgirl fantasy?

Spring Breakers doesn’t come out and say it, but it’s clear. This is what ‘spring break forever’ gets you. If you chase the party without restraint, you end up like Alien. There are such things as consequences, even in Florida.

You know that, right? Or are you a child? Did you believe that the world was like video games and music videos and only populated with perfect angels like Brittany Spears?

I see. Are you enjoying watching Spring Breakers? That’s nice. Pretty girls, right? Bang bang fun? Do me a favor. Watch it again in five years. Maybe two will be all it takes. Youth doesn’t last long.

At the end of the film, when our last two surviving party girls push their lack of inhibitions to a farcical degree, they still fail to recognize that their lives are actually their lives. They started their spree saying things like, “Pretend it’s just a video game,” and that’s what they did (except for Faith, who pretended that the earthly world was just a trial run for getting jazzed with Jesus). As their frenzy of sex and narcotics ramped up and on, it peaked as any bacchanal must: with sundered connections, with torn flesh, with the violent death of loved ones.

Do you know any Liberace?

Ah. Yes. Harmony Korine and Euripides. I knew that classical education would come in handy one day.

Brit (Ashley Benson) and Candy (Vanessa Hudgens) end the film by calling their families. What can one say after going on a murderous rampage in the name of spring break? Will the young women say, “I am sorry,” or “I have done wrong?” No. They will both, in their own words, tell their parents that now—only now—are they ready to be good. We are ready to be good in every way, in school, in life.

Because our youth, like spring break, has no consequence. Let’s forget it ever happened. Let’s throw our pink, unicorn-embossed balaclavas into the sea and drive home to be good. And let’s not accept for a second that our actions will mark us clearly—just like this symbolic, bright orange, brand new Lamborghini we stole from a gangster we slaughtered, and which we are now driving down the highway back to boredom, oblivious to the permanence of consequence.

And before you mutter something about the youth of today, get a grip. Korine is not skewering today’s youth, he’s skewering youth. Did you notice the handy-cam party footage that was sprinkled throughout Spring Breakers? All those shots of kids partying drunk and naked in lo-fi black & white?

No one’s phone today shoots lo-fi black & white, let alone a handy-cam. That’s the way footage might have looked when you were 19. Do you remember that? Or have you blocked out what it was like to be so immersed in youth you couldn’t even see tomorrow?

Korine obviously hasn’t. Spring Breakers is a candy-covered slap. You can ogle your way through it but by the end you ought to be ready to grow up and face the music, even if it’s a track by Skillrex.