Touch of Evil is Orson Welles’s best movie. Which is a scandalous thing to say in the movie world. Maybe not scandalous. How about sacriligeous? Citizen Kane is, after all, Citizen Kane. It’s tough to get around Rosebud being a sled. I ranted about Kane a while back, the gist of which rant was that while technically Kane is like watching one man invent the wheel and cure cancer at the same time, emotionally I find it rather cold and distant. Story-wise, it comes off a bit stilted. Whereas Touch of Evil is all emotion. It’s dark and earthy and subversively sexual. No wonder Universal hated Welles’s original cut, took the movie away from him, shot new scenes, edited their own version, and released it with nary an advertising campaign in sight.

So what I’m really saying is that the 1998 restored version of Touch of Evil is Orson Welles’s best movie. I’ve never even seen the originally released version from ’58, which is about twenty minutes shorter and includes scenes shot by another director, Harry Keller (some of which scenes Welles thought worked, and are included in the ’98 version). What exactly went down remains somewhat mysterious. Welles says he wasn’t invited back to direct the re-shoots the studio wanted. Others say Welles wasn’t able to do the re-shoots because he was busy acting in another movie. In any case, a few short scenes were shot, some good, others needed to bridge the 20 excised minutes of Welles’s version. The movie was assembled by Universal into a 108 minute rough cut. After screening it, Welles responded with a 58 page memo explaining in meticulous detail how the movie should be properly edited. (It’s one hell of a read, if you’re into that kind of thing (like me)).

Naturally, editing advice that exacting and brilliant was ignored by Universal, who pared their cut down to 93 minutes and released it as a B movie, the second half of a double feature. It didn’t do well in the U.S. In France it killed. But then they really loved noir over there.

In the ‘70s Universal discovered they still had the rough cut. They billed it as the restored and uncut version and released it. And then, finally, in the ‘90s, editor/sound designer extrodinaire Walter Murch (of Apocalypse Now fame, among many others) was hired to follow Welles’s instructions and create the cut Welles always wanted.

Many of the changes are likely more subtle than the average movie-goer would notice. Added together, however, they make a difference, a huge one, as Welles’s instructions touch on everything from placement of the credits to intercutting sequences to retaining the black humor to appropriate music cues, sound design, and scoring. He wrote the memo knowing he wouldn’t be allowed to make the changes himself; he’d actually been barred from entering the studio. He merely wanted someone to do what he asked, preferably 40 years before Murch finally did so. Hence the extremely detailed notes.

Regarding Welles’s instructions for “lousing up” the music to make it sound like it was coming from car radios, cantinas, and so on as the camera passed them by, Murch says:

What was astonishing to me, was that that very technique was something I thought I’d invented for film in the late sixties, and which I’d used extensively for a number of films, up to–and especially including–American Graffiti. But here Welles had already done it ten years earlier in 1958.

Touch of Evil is of course a film noir, coming at the tail end of what’s considered the prime noir years. The story of how Welles came to be involved was that he’d been hired to act in it only, until Universal tried to hire Charlton Heston, who said, more or less, “Orson Welles is in it? Why isn’t he directing?” Silence. Dial tone. Finally the studio got back to him with, “Did we say he wasn’t directing it? Silly us! He is now.” And so Heston signed on.

Welles, meanwhile, tossed the script and rewrote it, his condition for agreeing to direct. He thought it would be his ticket back into Hollywood. But as with all things Orson Welles, it didn’t work out that way. Has there even been a greater artistic genius more consistently thwarted than Welles in Hollywood history?

He opens the movie with a now famous single-take shot, beginning with a time-bomb being set to three minutes and stuck in the trunk of a car. The car winds its way past Heston as Mexican police chief Vargas and his new wife, Susie, played by Janet Leigh, until, three minutes later, it blows up, just across the Mexican border in the U.S.

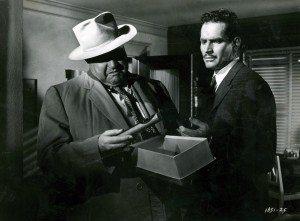

As the car burns and sirens wail, Welles makes his entrance as Hank Quinlan, a fat slob of a detective who mumbles his every bitter word and acts like he’s god on earth. He limps and walks with a cane and says he gets his hunches from his bum leg. Like an eager dog, his partner, Menzies (Joseph Calleia), follows on his heels and never shuts up about Quinlan’s genius for solving crimes.

The key scene comes soon afterwards. Vargas, Quinlan, Menzies and others head to the home of Sanchez, a young Mexican who secretly married the daughter of the man blown up, which daughter now stands to inherit his riches. Sanchez proclaims his innocence convincingly. Why would he commit such an obvious crime? Vargas goes to the bathroom and knocks an empty shoebox into the bathtub. Later Quinlan urges Menzies to check the house again for clues. Menzies finds two sticks of dynamite. Where? In the shoebox. Vargas knows it was planted, and accuses Quinlan of planting it. A clash of wills ensues.

Meanwhile, Susie has been taken to an out-of-the-way motel where a gang of Mexican thugs harasses her and eventually sets her up to look like a drug addict. Which all comes into play later on. The scenes in the motel are alternately ghastly and bizarrely funny. Welles loved the actor Dennis Weaver and has him play the part of night manager in the weirdest way imaginable. It’s a totally loopy performance.

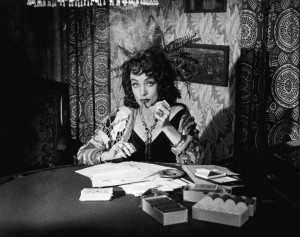

Just as funny, and much more in the realm of the real, is Uncle Joe Grandi, played by Akim Tamiroff as a man whose idea of how to be a tough guy he got from watching movies. He tries to threaten Susie only to have her call him out for the joke that he is. Later on he lures Quinlan into working together to get Vargas out of the way, but Quinlan’s a lot smarter than he is. Things don’t work out well for Uncle Joe, who, cornered in a motel room with Quinlan, realizes he’s in trouble when Quinlan pulls a gun. Welles describes that and what follows:

It was perverse and morbid—the kind of thing I don’t like to do too much. But it was one of those go-as-far-as-you-can-go—in that kind of dirty department. Tamiroff was great in it: when he looked at that gun, it was every cock in the world. It was awful, the way he looked at it—made the whole scene possible.

So there’s the plot, more or less, a seemingly straightforward noir, but it’s far from straightforward. The way Welles shot is like nothing that came before. The camera is in constant motion. It follows characters, gets up in their faces, rises above them. It’s strapped to the hood of a car for one scene of Vargas racing through town. Much of it is hand-held. The movie is in constant motion. There’s no looking away, and you want to look away, you want a break, and the movie never gives you one.

Which that’s one thing that blew me away at the screening of Touch of Evil I saw a few days ago, the speed it moves at. It feels modern. The dialogue is all overlapping, like an Altman movie, but where every line is pushing the plot forward. You almost can’t catch your breath watching this thing. Here’s Welles on a shot he thought better than the famous opening one:

But there’s, technically, a much more difficult crane shot in Touch of Evil which nobody ever recognizes as such; it runs almost a reel, and it’s in the Mexican boy’s apartment—it’s in three rooms—where the dynamite is found in the bathroom and all that; it has inserts and long shots and medium shots and everything. We had breakway walls…[It was shot] without a cut…and nobody realizes it. That’s a success. It’s much more of a shot than the famous opening.

The style of Touch of Evil is reminiscent only of the movies that followed it. If one may be allowed to reminisce about the future (which I am; long story). And it’s really not until the mid-‘60s when stylish European directors like Polanski and Antonioni began making movies (like Repulsion and Blow Up, respectively) we look at now as quintessentially “‘60s,” when really they’re imitating the kind of camerawork Welles pioneered almost ten years earlier.

Now one thing people like to joke about in Touch of Evil is Charleton Heston playing a Mexican. Which, granted, is kind of absurd. The thing is, Heston is great in this movie. Has he ever been better? Maybe in Planet of The Apes? Says Welles: “I think he has the makings of a great heroic actor…If he isn’t, then it’s the movies’ fault or the theatre’s fault for not giving him enough to do.” Welles gave him plenty to do.

It was only once shooting began that Welles cast Marlene Dietrich as an old friend (an old flame?) of Quinlan’s. Her part is small but crucial. The relationship she has with Quinlan is one of only two things that humanizes him (the other: he took a bullet once for Menzies, hence his limp), and her last line in the movie is a classic: “He was some kind of a man. What does it matter what you say about people?”

Welles used Touch of Evil as an opportunity to make a movie about something as simple as good and evil. As far as he was concerned, the movie’s message was obvious, and summed up in Vargas’s line, “Who’s the boss? The policeman or the law?” Vargas follows the letter of the law, whereas Quinlan does whatever it takes to punish the bad guys–bad as decided by Quinlan. As Quinlan says at the end, sure he planted evidence sometimes, but only on the guilty. Quinlan betrays the law. His partner, Menzies, betrays Quinlan to Vargas. And Vargas, who at the end sneaks around with unfamiliar recording equipment to spy on Quinlan, betrays his own values. “It’s all about betrayal, isn’t it?” says Welles.

Yes it is. Fitting in a demented way that Universal would betray Welles over it. They loved the footage as he was shooting it, but freaked out when they saw it edited together, the miserable cowards. Touch of Evil is a beautifully grimy, fast-paced, weird and funny movie. I can’t think of anything else quite like it. We’re lucky Welles knew he was getting shafted and wrote his memo, and that someone as talented as Walter Murch was given the chance to do as Welles asked. Touch of Evil is some kind of genius.

All the Welles quotes above are taken from the book This Is Orson Welles, a series of interviews done with director Peter Bogdanovich from ’68 to ’72, and a great read.

really liked this when I watched it ages back. not read the post yet but I saw this online a few months back, really liked it

http://vimeo.com/51466248

really liked this when I watched it ages back.

not read the post yet but I saw this video clip online a few months back and I really liked it, nice analysis of the famous opening shot:

http://vimeo.com/51466248

looks cool…though i don’t speak spanish.

I find Orson Wells a self-important bore most of the time. I rented Touch of Evil the first time because of the opening of The Player. Heard it was an homage. Good stuff.

This is a nice piece. I didn’t know there was two versions of the film. I will have to find the Walter Murch edited one now.

The Murch one is the one that’s out there, being that it’s the version Welles wanted (or as close to it as possible). It would actually be harder to find the originally released version.

Universal claims that Touch of Evil is being restored for blu-ray release later this year, so my guess is it’ll include the different versions.