You know the kind of movie I’m talking about. It’s the one in which the respected actor proves his or her chops by pretending to suffer from significant cranial distress.

We disparagingly call this kind of picture Oscar bait. And often enough these movies win Oscars, too.

There are other, less pretentious films, in which characters act crazy. Sometimes these roles call for actors to depict authentic mental illness. Other times, they roll out some sort of odd, amusing, quirky Hollywood-style mental illness. The kind that can be cured by a dance contest.

People think acting crazy is neato to watch! And often enough it is.

But I realized something this very week. The appearance of someone, even a very talented someone, acting as if mentally ill and the appearance of someone who knows mental illness first hand: these two things cannot be mistaken for each other.

That’s why actors need to stop acting crazy. Because they’re doing it wrong. I’m not even sure it’s possible to do it right.

Acting crazy is crazy, and not in a Catch-22 way. Just in a normal, simple, escapist way.

I understand that psychologically abnormal characters are interesting to watch, write, and (I assume) portray. But acting crazy is just that: acting crazy. Actually having a mental illness on the other hand, and then having the wherewithal to act despite of it (or because of it), that’s no charade. That’s a big, raw slab of toothsome emotional meat.

You see it. You recognize it. It shakes you. It is an honest sharing of frightening truths.

Those actors who ape insanity can be fully engaging in their roles. They make enjoyable and/or illuminating films. They do not, however, shake us in the same way as witnessing genuine mental illness does. Why should this be, that mental illness is so difficult to portray convincingly? Actors can convincingly mimic those of a different gender, age, physical condition, or even species. Not so the mentally ill. Why?

Do not try and bend the iguana. That’s impossible. Instead… only try to realize that it is not the iguana that bends, it is only yourself.

It is because mental illness is genuinely terrifying. In order to accurately act crazy, one must truly be, at least in part, crazy. Once you go there, there is no guarantee of a return ticket. Look at Nic Cage.

This marble-losing fear is potent stuff. It grabs us around the throat like a humping mass of butterflies. It rubs Ben-Gay inside of our ears and swaps our fingers out for tiny little tuning forks. If you’ve ever spent time with someone (including yourself) who has lost contact with reality, temporarily or permanently, you know of which I speak. It is a genuinely unnerving experience.

All of this is why I truly adore the performances in the films of Werner Herzog. Mr Herzog has an eye for the functioning lunatic. And yes, you may snarkily deride all actors as functioning lunatics, but saying so is discourteous to actors and to lunatics.

But those people who live their lives too close to the thrumming core and yet still politely invite us inside their heads for a performance? That’s incredible; honestly hard to witness and believe and digest.

By casting individuals with real experience with mental illness—such as Klaus Kinski and Bruno Schleinstein (credited as Bruno S.)—Wener Herzog trims back the protective cover of fiction. We are led into stories that are not true, but which feel true at a higher level, due to raw performance.

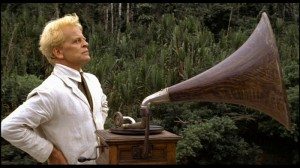

I watched a few films recently which brought all this into my head. Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and Stroszek both star Bruno Schleinstein. Bruno was not an actor, but rather a musician and forklift driver with a history of institutionalization. Herzog saw him in a documentary and instantly recognized a muse.

Despite his lack of acting training and his intense insecurities on set, Herzog made two films with Bruno S. In both of them, you follow a unique sort of befuddled man-child as he attempts to understand and interact with an unintelligible world. Through the eyes of Bruno we are able to glimpse our constructed society for what it is: madness. We do not delve into the personal demons of the man, we reflect upon the demons of our own combined creation.

You think Bruno’s crazy? Look at what you do every day of your life.

Of his star, Herzog said:

In all my films, and with all the great actors with whom I have worked, he was the best. There is no one who comes close to him. I mean in his humanity, and the depth of his performance, there is no one like him.

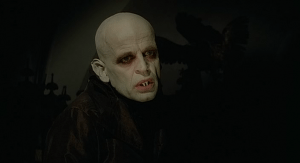

Werner Herzog also made five features with Klaus Kinski (Aguire der Zorn Gottes, Nosferatu, Woyzeck, Fitzcaraldo, and Cobra Verde), plus a posthumous documentary on their relationship, My Best Fiend. If you have seen any of these films—particularly Aguire or Fitzcaraldo—you will have no trouble identifying Kinski’s megalomania. He was a tormented supernova of powerful emotion and legendary rage. Herzog tells of how in order to get a performance from him he’d first have to infuriate the man, let him rant himself out, and then, in the momentary calm that followed, film.

What is it we learn from stepping inside Klaus Kinski’s world? In him, in his performances and in his skin, we see the ruin within our desires. Is the man crazy for trying to impose his will upon the chaotic world? If you’re feeling judgmental, try taking a look at what you do every day of your life.

Now these stories are assembled by Werner Herzog as writer and director. It is part of his genius to cast the right men for the roles. It is another part of his genius to choose the right stories to match the men who elicit such emotion from us.

While you might watch some of Herzog’s films and feel lost or disengaged, when they end you feel as if you have glimpsed something beyond words. Something visceral and elusive and, yes, crazy. Grizzly Man crazy. That is the combination of the director’s insight and his actors’ unvarnished exhibition.

That is the gift Bruno and Klaus shared with us, perhaps at great cost to themselves. They weren’t acting like crazy men. They were sharing the peculiar warp of their worlds with us via characters only as crazy as you or I may be.

Compare this to how it feels when we watch an actor pretend to suffer from mental illness. It is not at all the same experience. Recent Oscar bait includes The Silver Linings Playbook, which has two popular and well-regarded stars playing charades with manic depression, or A Royal Affair, in which a king runs amok afflicted with unspecified lunacy. You may have enjoyed these films (I did both, give or take), but I’ll wager neither moved you as much as Herzog’s work with Bruno or Klaus.

You cannot act crazy without actually being crazy, for acting crazy is an act, and being crazy mutates the entire world. In this new world, every once-familiar thing needs a new name. It is the act of renaming that allows us to clearly see the things to which we have long been blind.

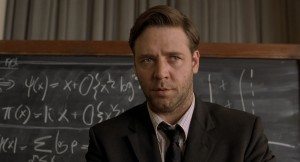

This week I also watched David Cronenberg’s 2002 film Spider. In Spider, Ralph Fiennes plays Dennis Cleg, a man just released from an asylum into a halfway house. For the entirety of the film, Fiennes immerses himself in the personality of a man insane and struggling. His dialogue, such as it exists, is mumbled and incoherent; his actions erratic and disturbing. It is a fine film and one of the most impressive portrayals of insanity I’ve ever seen.

I also had on Ingmar Bergman’s The Hour of the Wolf, a study of a man’s descent into insanity—the great Max von Sydow. The director is justifiably lauded for his emotional insight, his films’ exposed humanity, and his shadowy manipulation of vision. Von Sydow is hard to match for acting heft, a skill for which he has been rewarded with an illustrious career; eleven films with Bergman being just the start.

Neither performance compares well to Bruno Schleinstein’s or Klaus Kinski’s though. Ralph Fiennes is mimicking something he saw, maybe in real life, maybe in media—but he doesn’t have it living in his stomach. So, too, von Sydow. Watching them does not make me afraid. Being unafraid, I am not transformed. I see a confused, sad world, but not a new one.

And so it’s a different kind of thing entirely. It is the difference between looking at a photograph of the sea and swimming in it.

I can see that the sea is rough, and I do not envy those that tread the water just to stay afloat. I am grateful, however, for those that have chosen to share their experience with me, on film.

To the rest, please stop acting crazy.

In college I had to write a 30 page paper on Through A Glass Darkly. That was pretty insane.

What did you say? In less than 30 pages if you can summarize.

YES.

I’m a psychiatry resident. The internal realities of people with serious mental illnesses are almost never accurately shown on screen, and reductions to safe, understandable cliches are misleading. The portrayal of people with mental illness is generally exploitative.

I’ve seen exactly one performance by a person without a known psychiatric illness that reminded me strongly of my seriously and chronically mentally ill patients: That of Jeffrey Wright as ‘Al Melvin’ in Demme’s remake of “The Manchurian Candidate” (of which I can remember virtually nothing else). Most other performances are at best annoying, and at worst distorting/actively harmful.

Interesting. Does this mean I need to watch the Manchurian remake? I could never quite find the stomach for it…

I recalled what I first wished to say: You have grasped a truth most people spend their lives avoiding. Mental illness is terrifying, and one of the reasons that most performances ring hollow is that the foundation of so much of a mentally ill person’s rage is terror at a reality which constantly warps and twists out of their grasp, or threatens them with horrors that the people around them cannot imagine–or will not, because the ideas themselves are so frightening. I knew I wanted to do psychiatry after talking to schizophrenic patients about how they experienced the world every day, and realizing that the very act of talking to me represented courage of the highest order.

Maybe just try to watch Wright’s scenes? Don’t think the movie stood up well to the original, despite the star-studded cast. I recently rewatched scenes from “Rainman”(saw it first at age 12) and was impressed by Hoffman’s portrayal, as well. And I have been meaning to watch “Spider”.