Do you want to see something sparkly and wonderful, like the magical poop of unicorns? Well then let me introduce you to Liberace. Slowly.

Do you want to see something sparkly and wonderful, like the magical poop of unicorns? Well then let me introduce you to Liberace. Slowly.

Recently, I broke down and ordered HBO just so I could watch Behind the Candelabra, the strange-life tale based on the memoirs of Liberace’s lover, Scott Thorson. The film relates this young man’s odd tale of love and despair in the glittering, bejeweled, demanding embrace of one of the century’s most popular performers — Liberace.

That’s right. We love Liberace!

But what is this movie really about?

Is it naught but a biopic with an uncommonly rare set of subjects? Is it a neo-gothic tale of romance and tragedy? Why did director Steven Soderbergh feel driven to tell this particular story in this way at this point in his career?

Good questions. Thanks for asking. I’ll get to some answers in a second.

First off, I must say that Candelabra is stunningly good in many ways for much of its length. The fact that it never hit (American) theaters is a travesty. While I couldn’t call it Soderbergh’s best film, it’s leagues better than many of his last few (Side Effects, Contagion, etc.). It is undeniably fun and racy, but that’s just a coating of fairy dust. Underneath: powerful muscles and tanned flesh.

I cannot recall a set of lead performances — and I’m talking about Michael Douglas as Liberace and Matt Damon as Thorson — that were so overwhelmingly convincing and yet so in contrast to the actors’ actual personalities Here is Michael Douglas in the role of his career, playing a man who seems to be diametrically opposed to himself. I’m not talking about the fact that Michael Douglas is not gay, as that’s just the thinnest slice of it; I’m talking about his complete shucking of his own inherent character in favor of Liberace’s flamboyant, petulant, bizarre otherness.

That’s what we call acting and it’s amazing when you see it for real. We all have a little crazy in us, and we can imagine adapting to physical disability, but who among us could become so very, very Liberace? Not me, that’s for sure.

It is as if Douglas is possessed. You watch him. You recognize him as Michael Douglas, but no trace of Douglas remains. It is a terrible pity that he will not be eligible for an Academy Award because if he showed up in character to host, then I’d watch that endless catastrophe.

His performance is beautiful and stunning and tragic.

Matt Damon, too, whom I normally find less than fully compelling unless he’s twisting people’s heads off, deeply invests in his role as Scott Thorson. It’s a less flashy part, but playing foil to Douglas’ Liberace can’t be undemanding. He holds up well.

In this (as related as true) story, Thorson goes with his boyfriend (Scott Bakula) to Las Vegas to see Liberace’s popular show. Damon pegs Thorson as a shy, self-doubting soul with no real family. He’s gay, but — it being a significantly less tolerant 1977 — he feels safer keeping a low profile.

As does Liberace, sexuality-wise if in no other way. Despite the performer’s extravagant costumes and fey mannerisms — both of which are amusingly hard to believe — the world thinks he’s engaged to a female ice skater. It reminds me of how shocked I was to learn Boy George was gay when I was 13, a decade later. What one doesn’t understand and what one isn’t looking for is exceedingly easy to miss.

Thorson gets introduced to Liberace, or Lee as his friends address him, and the pair begins a long, intimate, corrupting affair. Perhaps it is a welcome sign of these modern times, but their homosexual relationship is depicted without pretense or coyness. The actors kiss, and fuck, and appreciate one another in ways heterosexual couples do and have done on-screen for decades.

Amid the displays of affection and disaffection, you might forget that you’re watching Damon and Douglas. I often did.

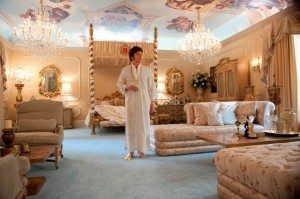

As the years pass, Scott Thorson becomes encrusted with the “palatial kitsch” that overlays Lee’s world. He is adorned in furs and sequins and giant gold rings, but he’s being pampered like a child and not elevated as an equal. The real gifts are only half given. So Scott is coddled and loved, but there’s something missing. Maybe it’s the fact that they’re not really family? Watch Lee try to adopt Scott. Maybe it’s that they don’t share the same genes? What could they do about that?

If you’ve heard anything about Behind the Candelabra, perhaps it’s been hints of the plastic surgery Lee insists on Scott getting to make Scott look like Liberace as a younger man. Through his lover and pseudo-son, Liberace could live forever, a la Dorian Gray.

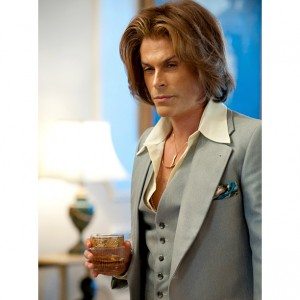

Even if Liberace and love seem unappealing to you as subjects (you heathen), you’ll want to witness Rob Lowe’s hysterical scenes as the plastic surgeon, Dr. Jack Startz — a man with his face stretched so tight you could pop his cheeks with a bristly-bearded kiss. Is he laughing? Is he in pain? Hard to say. Have another pill and wash it down with whiskey.

Lowe is fantastic and so, surprisingly, is Dan Aykroyd, which is frankly amazing given the man’s record of making perfectly terrible films. Also elating is the cinematography. I watched this film and wanted to pause frame after frame so I could savor Soderbergh’s delicious use of color and composition.

Soderbergh has always been good behind the camera, but here he almost outdoes himself. It reminds of Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, but instead of that film’s painterly appearance, this one gleams like Diana Ross captured mid-croon. It sparkles like a gem. It sets before you tableau after tableau all set to soothe you with their simple, elegant, rightness. The soft nap of ’70s orange. The coolness of a pale blue shirt pulling focus. The haze of candlelight, flickering fractals of color to create wonder.

It’s as if Soderbergh — cinematographer as well as director — is saying, “See what you’re going to miss, Hollywood? This is what you need to get ready to kiss goodbye.”

And that’s honestly what I think the film is about. The story of Thorson and Liberace’s love is worth telling for its strangeness and its humanity, but I think this project is more personal for Soderbergh than that.

Soderbergh, I surmise, sees himself in Thorson. He, too, was once a young man, full of dreams, who fell for the glitter of success on the wane and the illusion of established security. Thorson was a man who changed who he was, how he appeared to the world, so he could lose himself in what he loved. But the love soured. Hollywood — I mean Liberace’s — need became too demanding and too jealous even while it was busy philandering away. So Thorson — Soderbergh — became trapped and lashed out. From the outside, that rebelliousness may seem foolhardy. Perhaps this is how it feels from the inside.

At last a time comes when simple displays of affection between the the pair become so rare they bring tears.

And then it’s over. Thorson is shown the door and left to fend for himself. They were like family, but not family. They were like kin, but all too easy to excommunicate. You were like a son to me, but one can always get another son.*

Heading into the second half of Candelabra, the film becomes less engaging. The romance between Liberace and Thorson evolves and sours and turns tawdry. I found myself impatient for the inevitable acrimony.

Perhaps that’s also how Soderbergh felt, struggling to make his films his own way. Finally forced to make this one — a nice big shining moon in Hollywood’s face (with a Brazilian tanline) — a step outside of the system.

Or perhaps I’m wrong. Maybe Behind the Candelabra is just a film about a crazy love affair. Either way, it’s a film worth watching. If this truly is Soderbergh’s last feature, he’s gone out with a bang.

At the end of Candelabra, there’s a fanciful musical number that I’ve heard disparaged as out-of-place. I completely disagree.

We close with Scott, at Lee’s funeral, imagining and remembering what he first fell in love with. This old man, with his grey face and bald head, now stripped of his furs and sequins and gold; he was once truly — in his own way — a purveyor of dreams. A genuine showman.

And even after all the heartbreak and cruelty and deceit, it’s wrong to forget that once he made us very happy. That happiness exists still, in our memories and in the movies.

* …but there is only one Maltese falcon.

Oooh, I’ve got to see this one.

it’s definitely worth a watch.

BtC is indeed a great little flick. I think Soderbergh’s last few are all great though, including The Girlfriend Experience.

Matt Damon’s pinnacle performance of his career is in The Informant! And I doubt he will ever top it.

I’m a huge Soderbergh fan but I haven’t adored all his latest. All decent films, but less compelling than he’s capable of — or than BtC. Side Effects was a nice little thriller, but the last act abandoned a lot of potential for something familiar. Contagion… it just didn’t scare me. I did like Haywire and Magic Mike quite a bit.

I suppose it’s time to re-watch The Informant! I liked it when it came out. Do you think that Damon’s performance there is better than his Scott Thorson? I’m not sure. Scott is a muted character in a lot of ways, but it’s a strong performance from Damon. Or for Damon. I’m not positive which.

Both performances is layered, but The Informant! keeps asking how far is Damon capable of going,… and the film keeps adding that, right up until the older-version of himself.

Also, I’m a complete sucker for his Voice Over in that film…It positively kills me, and just adds to the character.

You’ve convinced me. Time to queue that up again. I only saw it the once when it was in theaters.

The Informant! might be Soderbergh’s best comedy.

Finally saw this. Thought it was very good. As you say, it’s unbelievable this wasn’t out theatrically. It would have done plenty of business. Douglas and Damon are both fantastic. And I thought the end was just what it needed to be. Reminiscent of All That Jazz, in that musical sort of way.

Yep. And I re-watched The Informant! not too long ago; also amazingly good. I may have to work Candelabra into a double feature soon… too many people missed it completely.

It’s amazing how Michael Douglas became Liberace! He and Damon did some of the best work of their careers. I just can’t believe America didn’t know Liberace was gay…and he actually sued a London paper for saying so…and WON!

Indeed. But then I recall being shocked- SHOCKED- to find out that Boy George was gay. Granted I was 12, but still. It was a different, shittier time known as the 80s.

Douglas should have won an Academy Award for this film.