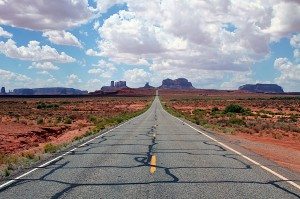

If there’s one thing we’ve got here in the good ol’ U.S. of A., it’s roads. Roads and freedom, the two things we’ve got in America. Or at least the roads, anyway. Maybe not as much freedom as we imagine, or wish for, or dream of. We’ve got roads and because of all the damn roads, we’ve got road movies. Those are the two things America has, dadgummit! Which a road movie is a movie where a couple of characters—sometimes more, never fewer, but usually only two—hit the road. They’ve got a destination, but the destination isn’t the point. The road is the point. They meet people. They become sidetracked. They have adventures. They learn about themselves. Or they don’t.

The open road seemed more mysterious in days gone by. No internet connected the world. If you wanted to see the world, you had to go there. To the world. Which I swear is around here someplace.

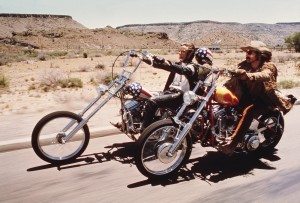

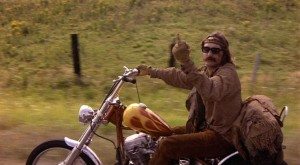

The road represents freedom. Aha, that’s it! If you want your share of that fabled American freedom, you’re not going to find it in a house, at a job, working for the man, following the man’s rules. The only freedom is the freedom to be in motion. And if while you’re in motion you’re on a motorcycle, even better. That’s the freest freedom there is, the wind whipping your hair, the engines destroying your hearing, driving hard and fast to somewhere that’s really nowhere at all, because the moment you arrive, it’s time to go.

For this week’s Mind Control Double Feature, we ask the hard questions: is freedom out there? If it’s out there, how do we find it? And if we find it, what the hell do we do with it?

Easy Rider (’69)

No one involved in making Easy Rider expected a watchable movie to result. Dennis Hopper, who directed it and co-wrote it with Peter Fonda and Terry Southern, was by all accounts a megolomaniacal madman before, during, and after the shoot. Hopper spent over a year editing the footage into a French New Wave-inspired four hour experimental film. Finally the producers paid for him to take a vacation in Taos, during which they cut it down to 94 minutes. Hopper was outraged at first, but came to accept it (before or after the money started rolling in I’m not sure).

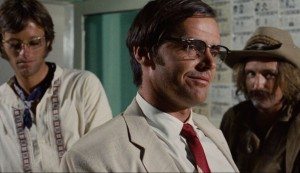

Easy Rider was a new kind of movie. It’s no wonder nothing was expected to come of it. Where was the plot? Where was any coherent story? Some said Southern provided the title and nothing more, that all the dialogue was improvised. Jack Nicholson, who plays drunken lawyer George Hanson, said it was scripted tightly to appear improvised. That’s the Nicholson who, by the way, was a b-movie actor going nowhere at the time. He kills it in Easy Rider. Next he played the lead in Five Easy Pieces, and a star was born.

The movie spoke, as they say, to a generation. In ’67, Bonnie & Clyde and The Graduate started the conversation, but they weren’t made by a bunch of inexperienced, drug fueled hippies (and neither was Midnight Cowboy, also from ’69, also a plotless tale of two outsiders). Other movies, like Roger Corman’s ’67 The Trip, a psychedelic story of a man’s first LSD trip (that starred Fonda and featured Hopper), were too small and focused on drug use to get much play. Easy Rider broke through. It was about America, and the new civil war being raged within it between the new generation and the old. When Easy Rider premiered at Cannes, Fonda dressed in 1860s Civil War attire.

Best of all, Easy Rider is still great. I watched it last week to find out. It had been years since I’d seen it. I barely remembered it. I imagined it was amateurish and boring, maybe because I’d read so much to that effect in the years since. Even people praising Easy Rider have a tendency to point out what a mess it is.

It’s not a mess. It’s not boring. It’s a template for a breed of movie that would thrive during the ‘70s. It’s a road movie, plain and simple. It might as well star Bing Crosby and Bob Hope and be named On The Road To New Orleans. But with cocaine and LSD.

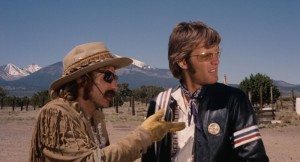

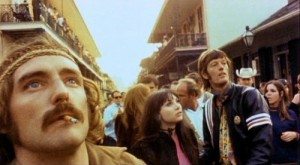

Which going to New Orleans is the whole story. The movie opens with Wyatt and Billy (Fonda and Hopper, respectively, wishing they were old western gunslingers) buying cocaine from Mexican drug dealers, then selling it to a rich guy (Phil Spector). They stash their earnings in the gas tank of Fonda’s awesome motorcycle, and hit the road for New Orleans. Along they way, they find an America that’s not at all happy to meet a couple of longhairs on motorcycles. At the end, they take acid at Mardi Gras, freak out in a graveyard with a pair of prostitutes (Karen Black and Toni Basil), and then…then it ends rather sadly. If you don’t know, I won’t say, but this is no happy adventure.

Fonda says famously at the end, “We blew it.” What does he mean, exactly? You’ll have to figure it out for yourself. It was a line much debated when the movie came out.

Neither Fonda nor Hopper show off much in the way of acting chops, but they’re perfect in these roles. Hopper as the nutty, obnoxious idiot, Fonda as the quiet, laid-back, dreamy hippie. Neither says a whole lot. Nicholson’s is the best role, the alcoholic lawyer whose two great speeches make the movie. The first is a completely nutty one about Venusians, and in the second he explains that people hate Wyatt and Billy because they’re scared of them; they’re threatened by their freedom.

Again, considering the rep the film’s making has, it’s surprising to see how good it looks. It was shot by then unknown László Kovács (who’d later go on to shoot eight million movies, including Five Easy Pieces, Shampoo, and Ghostbusters, to name three), and he gives the movie a beautiful look. The desert landscapes glow and the colors are deep and dark.

Then there’s the music. It was a new thing to score a movie with current rock songs. A thing instantly adopted and used to excess ever since. The soundtrack includes Steppenwolf’s “Born To Be Wild” most famously, along with tunes by Hendrix, The Band, and The Byrds, among others.

It’s a weird movie. What’s it saying? Sure, it’s the hippies against the old world, it drove countless people to ditch their lives, or at least to dream of it. Yet the movie opens with the hippies selling coke to the strains of Steppenwolf singing “Goddamn the pusher” over and over again. Wyatt and Billy find a beautiful hippie commune, shot in soft-focus, no less, but it doesn’t quite come off as magical, and they leave as fast as they can. Wyatt and Billy may be free, but how do they use their freedom? According to Wyatt, they blow it.

Lost In America (’85)

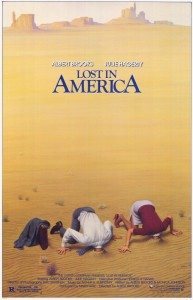

In which wealthy ‘80s yuppies David and Linda (Albert Brooks and Julie Hagerty), inspired by Easy Rider, ditch their lives, quit their L.A. jobs, buy a Winnebago and hit the road, free at last.

Lost In America is all about Albert Brooks. If you think Woody Allen is too much of a neurotic whiner, you’d best stay away from Brooks. Most scenes in the movie are essentially these epic monologues of insane neuroses run wild. The opening scene is especially wonderful, with Brooks in bed, unable to sleep as he runs through every possible thing that could be wrong with he and Linda moving to a big, new, expensive house, and whether or not he’s sufficiently worried about the promotion he’ll be getting in the morning. Does he get the promotion? What do you think?

But it’s a blessing in disguise! Linda tells a co-worker that her life is boring, that it’s going nowhere, that the excitement is gone. When David tells her he quit, tells her to quit, and tries to fuck her right there in her office, she realizes life just got interesting again.

So they decide to sell everything and use the proceeds, over $100,000 in ’85 dollars, to buy a motor home and hit the road, using the rest as their “nest egg.” David brings up Easy Rider as their role model over and over again, apparently forgetting how it ends. The motorhome chugs out of L.A. to Steppenwolf’s “Born To Be Wild.”

Everything goes horribly wrong, of course, leading to many hilarious scenes, perhaps best of all the one where David tries to convince casino owner Gary Marshall to give them back their lost nest egg.

Eventually they’re reduced to getting such jobs as crossing guard and fast food cashier. Do they give up their dream? After all their hardships? Which really only amounted to like two weeks, if that? Well, I’d hate to give it away, but…

It’s a little disconcerting, but the third act of Lost In America, in which our heroes tear ass to NYC, lasts exactly as long as it takes Sinatra to sing “New York, New York.”

Here’s the thing about Lost In America. It seems like a comedy. It’s funny, it’s over-the-top, it’s got comedy structure, it stars comedy actors (and by the way, Julie Hagerty must be the most underappreciated comedic actress of the decade. In this and Airplane! she’s fantastic). For all intents and purposes, it’s a comedy. Only then you think about it a little. Thematically, it’s about the emptiness of Reagan-era greed, of yuppies unhappy with their money-centric world who want to be free the way the ‘60s icons of their childhood seemed free. They want to be Wyatt and Billy. They always did, but never had the guts.

And then what happens? At the first sign of adversity they call it quits and run back to their empty, unhappy world of shallow greed, and it’s played like a happy ending. Albert Brooks the character may have forgotten the end of Easy Rider, but not Albert Brooks the filmmaker. Lost In America is really no more upbeat than its inspiration.

Is the freedom found on the open American road nothing more than an illusion? Are we trapped no matter how fast we drive? One of these movies is an inspiration. The other is a comedy. They come to similar conclusions. Best to keep driving and think about something else…

Road movie with fewer than two characters: Brown Bunny.

I thought there were some amazing parallels in the way the storytelling and the main characters’ existential “drive” were working in Jack Kerouac’s book On The Road and in Easy Rider. In both we watch some relentless gravitational pull of the main characters towards SOMEWHERE and SOMETHING and yet, at the very same time both, On the Road and Easy Rider ooze the feeling of we-are-not-getting-anywhere. That per se I considered the basic and immanent dilemma of America and to make it palpable and plausible in any form of art is both difficult and full of merit.

When I first wached Easy Rider as a very young girl, I could not help a strange feeling of stomache tightness that did not leave me until the cruel end. I had not read or heard anything before about the film, so I assume my senses picked up that hidden feel of doom and translated it into my anxiety. And if that’s so, then I guess the film was better done and maybe conceived than it might appear.

Anyway, will have to rewatch it soon to find out if there has been any change in my perception of the film (and of America’s reality) since my last visit …

Definitely worth re-visiting. I’d only watched it once in high school before watching it again (semi)recently. It’s a great movie. And yes, an unease permeates it. As cool as these guys are, zipping around the country on their cycles, they have no real destination in mind. Movement is the only goal.