Summer is upon us like a sweaty pro-wrestler wielding a folding chair, and you know what that means, right? Yes. It’s time to get on your bicycle and ride as far as the eye can see (assuming you have pretty poor vision after being hit with that chair).

The heat! The fresh air! The exercise. So healing and calming. Let’s ride to the beach and throw marshmallows at whales! Let’s ride up to the top of St. Nervin’s Meek and puke from the exertion! Oh, it will be glorious indeed. And all the children will sing and dance and lament the death of the telegram.

But wait. Something is wrong. I swear I left my bike right there, locked up to this Bichon Frise. Yes. Here is the chain, but where is my bike?

WHERE IS MY BIKE!!?!?!?!?

Well, I warned you to keep a close eye on your wheels. But did you listen? Did you hire armed bike guards or get some of those cement bike shoes or paint the thing invisible? No. And now your precious bicycle has been stolen.

Might as well cancel summer and put away the folding chair. Summer without a bicycle is almost too wrong to contemplate. It’s like… a murderous Superman or mustard-flavored Jell-O.

In order to prevent this calamity from befalling you, we have assembled this Mind Control Double Feature that specifically illuminates the utter misery that lies in wait for suckers what get their bikes stole.

Do not let this be you or you will make the professional wrestler cry.

Bicycle Thieves

Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 masterpiece, Bicycle Thieves, is one of those classics that you actually need to see. Not only does it play a major role in the evolution of film, but it’s powerful and intense and just damn great.

Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 masterpiece, Bicycle Thieves, is one of those classics that you actually need to see. Not only does it play a major role in the evolution of film, but it’s powerful and intense and just damn great.

After the Second World War, most of what people were seeing in the cinemas — and we’re talking internationally here — was feel good, song and dance, Hollywood escapism. That made sense. War isn’t a lot of fun and people having a rough time want to distract themselves from misery.

If you lived in Italy, however, the misery of war was harder to escape. Pretty much every major army in the world had just rolled up and down the length of the peninsula you lived on, grew your crops in, and depended on to support you and your family. Enter a new genre known as Italian Neo-Realism. Not to get all film school on you, but in brief, this was a new approach to making films. Instead of capturing a fabulous and fake reality, directors such as De Sica took pains to show the world as it actually was; i.e. the ‘new realism’ of the authentically poor.

Instead of shooting on big, glamorous sets covered in pink and yellow chiffon, directors like Visconti and Rossellini shot on real streets with non-actors. The stories they told were stories of poor and working-class people going about their difficult everyday lives.

And all that came to a head in Ladri di Biciclette, incorrectly translated in America for years as The Bicycle Thief. The story is remarkable for a number of reasons, but complexity isn’t one of them. Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani) is losing the uphill battle to find work in Post-War Rome. He’s got to feed his wife Maria (Lianella Carell), his son Bruno (Enzo Staiola), and his baby; but how? This is how Bicycle Thieves starts: at the bottom.

And all that came to a head in Ladri di Biciclette, incorrectly translated in America for years as The Bicycle Thief. The story is remarkable for a number of reasons, but complexity isn’t one of them. Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani) is losing the uphill battle to find work in Post-War Rome. He’s got to feed his wife Maria (Lianella Carell), his son Bruno (Enzo Staiola), and his baby; but how? This is how Bicycle Thieves starts: at the bottom.

If it were a Hollywood film, you’d expect some dramatic turn to offer Antonio a chance at wealth and salvation. This is not a Hollywood film. What he gets is the offer of a job pasting up posters, which would be enough to keep the family alive, except he needs his bike to do the work and he’s hocked it. So just start there; this is a film in which a bicycle means the difference between the hope of survival and the reality of the downward spiral into total despair. There’s no rich aunt with a million dollars and a kooky will. There’s a menial job, but Antonio needs his bicycle to do it.

Maria insists on pawning her dowry bed sheets so the family can reclaim Antonio’s bike. At the pawn brokers, Di Scia shows us the transaction as Maria’s precious, sentimentally invaluable treasures are tossed on a huge pile of other such linens. This is Italy. This is Rome. And this is also the happiest moment of the film. How’s that for a kick in the teeth?

Maria insists on pawning her dowry bed sheets so the family can reclaim Antonio’s bike. At the pawn brokers, Di Scia shows us the transaction as Maria’s precious, sentimentally invaluable treasures are tossed on a huge pile of other such linens. This is Italy. This is Rome. And this is also the happiest moment of the film. How’s that for a kick in the teeth?

They all pile on the bicycle and feel hopeful and fortunate. That’s as good as it gets, because shortly thereafter Antonio’s bike is stolen. The rest of the film follows Antonio and his young son Bruno searching, fighting, and longing for the missing bicycle.

Despite the depressing reality Ladri di Biciclette presents, the film is a treat. Di Sica’s black & white imagery does not gild, but instead manages to draw forth the simple beauty in everyday life. Young Enzo Staiola as Bruno serves as our eyes in the film; through him we observe the painful struggle of Antonio and we feel every setback. The boy was not an actor, but rather the son of a flower seller whom Di Sica noticed stealing a moment to watch the production. He’s brilliant.

Despite the depressing reality Ladri di Biciclette presents, the film is a treat. Di Sica’s black & white imagery does not gild, but instead manages to draw forth the simple beauty in everyday life. Young Enzo Staiola as Bruno serves as our eyes in the film; through him we observe the painful struggle of Antonio and we feel every setback. The boy was not an actor, but rather the son of a flower seller whom Di Sica noticed stealing a moment to watch the production. He’s brilliant.

By the end, Bicycle Thieves has taken us on a small journey with immense emotional impact. Something as simple as a bicycle, how could this ever mean so much in a piece of Hollywood fantasy?

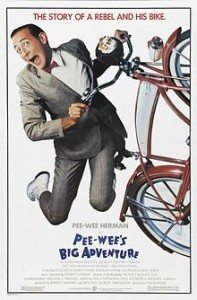

Pee-wee’s Big Adventure

If Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is not the perfect response to Bicycle Thieves, I don’t know what is. There are many reasons I can imagine a person having for rolling their eyes at Pee-wee and opting not to watch it. All of them are stupid.

If Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is not the perfect response to Bicycle Thieves, I don’t know what is. There are many reasons I can imagine a person having for rolling their eyes at Pee-wee and opting not to watch it. All of them are stupid.

I know you are, but what am I?

Yes, Paul Reubens’ Pee-wee Herman character is an overgrown, anachronistic, bizarre man-child. Yes, he lives in a strange world of color and kitsch and fantasy. This film, however, is pure joy.

In it, our hero Pee-wee Herman loves nothing so much as his precious bicycle. So, of course, it is stolen by his evil neighbor Francis, forcing P.W. to go on a cross-country search for his lost two-wheeler. Many adventures are had, all of them unbelievable in every way.

Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is fantasy from the ground up. It is also Tim Burton’s first and best film. Before he turned Johnny Depp into a life-sized Troll doll, Tim Burton made unique, dark, fantasies that refracted the normal — much like David Lynch on a pitcher of Kool-Aid. Beetlejuice, Edward Scissorhands, Ed Wood; these films all peel back society’s toupee to bounce light off its embarrassingly shiny skull.

Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is fantasy from the ground up. It is also Tim Burton’s first and best film. Before he turned Johnny Depp into a life-sized Troll doll, Tim Burton made unique, dark, fantasies that refracted the normal — much like David Lynch on a pitcher of Kool-Aid. Beetlejuice, Edward Scissorhands, Ed Wood; these films all peel back society’s toupee to bounce light off its embarrassingly shiny skull.

Trying to explain Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is like trying to paint a ballet. Forget it. It is a motley plateful of character humor, sight gags, surprise, and camp. For this, most of the credit must go to Reubens. If you have not had the chance yet, I highly recommend finding a copy of The Pee-wee Herman Show to watch as well, and I’m not talking about the kids’ television program — I mean the original stage show put on by the Groundlings comedy troupe in Los Angeles. This is where the character was born and where it runs most rampant. It’s also where Reubens and the late, great Phil Hartman began working together.

Hartman, whom you hopefully recall from his days on Saturday Night Live and News Radio and elsewhere, was brilliantly funny. He helped write the script to Pee-wee’s Big Adventure with Reubens and Michael Varhol.

This is also the first film to feature a score by Danny Elfman — now the king of film music (Randy Newman is the queen. Or the duke?) At the time, he was playing with his band, Oingo Boingo, and had never written a score. Guess what? He’s pretty awesome at it. Imaging Pee-wee’s Big Adventure without the music is impossible. The score is, in fact, the first thing I think of when I hear the title. That and Large Marge.

What else can I tell you about Pee-wee? It’s almost impossible for me not to just dive full-on into a litany of quotes from the film, almost every scene of which is indelibly branded into the fleshy bits of my headparts. But I will resist. I will simply tell you that I pity the fool that don’t watch this film. And to keep a close eye on your bike.