Say! Look at that! A small piece of cheese has been discarded on the sidewalk. You know what that means, don’t you? Surely you know how to “read cheese,” as the old timers put it? Well, no matter. Allow me to explain in excrutiating detail how this piece of cheese proves that Oswald didn’t act alone, that all religions are lies, and that Deckard is a replicant.

Not obsessed with cheese? You’re obsessed with something, aren’t you? Admit it! Obsessives are everywhere, thinking about everything, putting the pieces together—and christ, buddy, you wouldn’t believe the number of pieces!—proving something VERY VERY important. Here, they’ve written all about it. Handwritten it, even, in what amounts to 1 point font spread across 97 unlined notebooks. Read it. NOW. And know THE TRUTH.

They’re scary, the obsessives among us, but they’re invaluable, too. Every great leap in knowledge has come from the obsessive thinking and noodling and ruminating and experimenting of obsessives. And many stupid non-leaps in knowledge have likewise come from obsessions. Otherwise normal, healthy people are forever in danger of becoming obsessed by anything at hand, be it stamps or butterflies or rocks or blimp manufacturers or fake vomit shapes that resemble Barbara Billingsley’s profile. One could even, perish the thought, become obsessed by movies, and spend lord knows how many hours scribbling one’s obsessive opinions thereupon for other obsessives to read and obsess over.

Or one could obsess over murder.

This week’s Mind Control Double Feature is all about murder. Or is it about imagined murder? We will be looking deeply into photos and a painting, in each of which a murderer is identified. Isn’t he? Come, look closer. I have much to explain…

Blow-Up (1966)

The thing about Blow-Up is that watching it you’re going to become bored. Bored and distracted and lost. You’re supposed to feel this way. This is, after all, a film by Italian Michelangelo Antonioni, famous for his weirdly bleak movies about mysteriously unfeeling women wandering through barren landscapes, movies like Red Desert and L’Avventura.

Blow-Up is different. For one thing, it’s in English and takes place in a very swinging, very mod ‘60s London. For another, it stars David Hemmings, a man, as the unfeeling wanderer, a photographer named Thomas. And finally, unlike the usual Antonioni movie, this one actually hints at having a plot.

Which plot is this: Thomas, after photographing various models, becoming bored, and driving his expensive car around London (and casually saying things like, “I wish I had tons of money. Then I’d be free.”), finds himself in a park. He spots a couple kissing and walking around and surreptitiously photographs them from many angles, at many distances. Eventually the woman, Jane (Vanessa Redgrave), sees him, runs up to him and demands he give her his film. He laughs her off.

Later she shows up at his apartment (how’d she find him?), and again demands the film. Naturally, they have a bit of a roll in the hay. And he gives her the wrong roll.

When he develops the film, he thinks he sees something in one of the prints. He blows it up, over and over again. It looks like there’s a hand with a gun sticking out of the bushes. It looks like Jane is pointing to it. In another photo, it looks like the man is lying dead on the ground.

Or is it illusion? The image is so blown-out, so grainy, couldn’t it all be in Thomas’s imagination? You know he’s going to go back to that park to seek out the body. Will it be there? Will strange men come to swipe his negatives?

Blow-Up has undergone far more critical thought than I’m going to give it here. Essentially, it’s about the meaning we decide to ascribe to our lives. Is it there without our deciding it is? The movie has a very telling ending involving mimes playing tennis. A scene you’ve no doubt been dreaming of one day seeing. Preferably in a Michael Bay movie.

Blow-Up is perhaps more timely now then ever. Here’s what Bosley Crowther, famous if not rather curmudgeonly critic for the New Yorker wrote about it back in ’66:

This is a fascinating picture, which has something real to say about the matter of personal involvement and emotional commitment in a jazzed-up, media-hooked-in world so cluttered with synthetic stimulations that natural feelings are overwhelmed.

Indeed it does have something to say about your media-driven, synthetic world of ’66, Bosley.

Thomas goes to a club where the Yardbirds are playing (Hey! There’s Jimmy Page! And Jeff Beck too!). Beck destroyes his guitar ala Hendrix/Townsend, tosses the neck into the crowd. Thomas grabs it and there’s a huge struggle. Everyone wants that broken neck! Thomas runs, the crowd gives chase, and suddenly he bursts out of a side door to find himself on the street. He takes a look at the neck, tosses it to the sidewalk. A bystander casually glances at it, picks it up and wanders away.

So, what meaning does the guitar neck have? Is it intrinsic?

One of the models Thomas photographs is in a hurry; she has to catch a plane to Paris. When he runs into her later at a wild party and says he thought she was in Paris, she says “I am in Paris!” Is she?

Blow-Up is also notable for its nudity. Which by today’s standards is no big deal, but at the time it went against the then-in-use MPAA Production Code; it was not approved for release. MGM released it anyway. It was a huge hit, and a prime reason the ratings system we now have was put into place.

Blow-Up was a huge hit. Did you catch that? A weird, meandering, oblique movie, obscure and open-ended, was a huge hit in ’66. In adjusted dollars, it grossed about $120 million. It’s safe to say they don’t make movies like this anymore. And if they did, nobody would see them. Nobody would care. Movies, especially by heady, arty foreigners, meant something in days gone by. They were at the forefront of the cultural conversation. Today we talk about superheroes and political cheerleading.

In short, we have failed to maintain an interest in the language of film. Our obsessions have become depressingly literal and simplified. Which brings is to our second feature:

Rembrandt’s J’Accuse (2008)

What, you thought Coppola’s The Conversation was next? Or DePalma’s Blow-Out? You can watch those on your own time. What we have here is something a little different.

Peter Greenaway is a British director known for painterly films such as Drowning By Numbers, The Pillow Book, and The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover. He is a man obsessed by imagery, and how to communicate through it. Frames of his films are arranged like paintings, like still-lifes overflowing with flowers and objects, light and color.

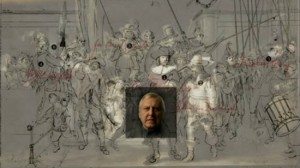

Rembrandt’s J’Accuse is a departure for him. It’s a documentary. Sort of. More accurately, it’s a visual essay, or opinion piece. It’s an argument. The overall thesis of the film, as narrated by Greenaway with his precise, erudite British diction, is that as a culture we have become visually illiterate. To illustrate this point, he directs our attention to the third most famous painting in the world (according to Greenaway), behind the Mona Lisa and the Sistine Chapel, Rembrandt’s The Night Watch.

In his typically detailed way, Greenaway proceeds to go through 34 reasons why this painting is in fact Rembrandt’s accusation of murder, with the murderer himself depicted.

To do this, Greenaway details the history of the times leading up the creation of the painting in 1642, he details the people in the painting, the reason for its existence, the way in which Rembrandt went about painting it, and, of course, he recounts the particulars of the murder to which Rembrandt refers in his accusation.

The movie includes re-enactments of various scenes, starring Martin Freeman of The Office and The Hobbit as Rembrandt. These scenes are weird and kind of bad, but you won’t care because it’s a documentary anyway.

It’s an unimaginably obsessive documentary. The hard part of watching this movie is keeping up with Greenaway. The man does not waste time. Every sentence is packed with information. You might want a cup of coffee for this one.

Does his argument convince in the end? By reading the painting, will the accusation of murder necessarily be found? Or is it only in the eye of the beholder? In this case, the very obsessive eye of Greenaway?

As with Blow-Up, it’s up to you to decide. Reality is what you make it.