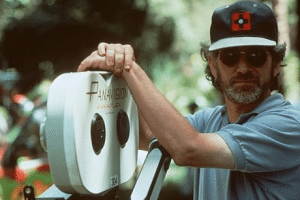

Steven Spielberg is a peculiar figure in the history of movie directors. He started out as a well-reviewed wunderkind, was then castigated by critics for years as an unserious director of popcorn movies before abruptly turning into an elderly statesman of serious dramas and family-values sci-fi/adventure/etc., the former of which the establishment can’t praise highly enough, the latter of which continue to earn boatloads of cash. And somewhere in the middle of all that, he started a studio, Dreamworks, where he produces and executive produces still more blockbusters by other directors. He is even, now and again, referred to as the greatest director of all time by publications that will remain nameless. Worldwide, his movies have earned almost $9 billion at the box office.

Has there ever been a director with higher name recognition? Hitchcock in the ‘60s? George Lucas? Maybe. I think if you asked random people to name one film director, the name you’d hear most often is Spielberg. He’s directed 27 theatrical features, numerous TV shows and TV movies, and various other odds and ends. Along with Lucas’s Star Wars series, Spielberg’s Jaws, Close Encounters of The Third Kind, and Raiders of The Lost Ark are credited (or blamed, depending on your outlook) with ushering in the modern era of the blockbuster, in which we’re still hopelessly stuck, in large part because the kids Spielberg inspired are the ones presently running Hollywood.

When Spielberg started out in the ‘70s he was lumped together with the other young directors of the era, an era when directors, for a brief time, were king. They could make anything they wanted. So Scorsese made Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, and Raging Bull, Coppola made The Godfather, parts I and II, and in between those his pet project The Conversation, then drove himself mad making Apocalypse Now, Bogdanovich made The Last Picture Show, Woody Allen went from anarchic slapstick to re-inventing the romantic comedy in Annie Hall and Manhattan, with a detour into Bergman and Fellini homages with Interiors and Stardust Memories, Sydney Lumet made Dog Day Afternoon and Network, De Palma made Dressed to Kill, Rafelson made Five Easy Pieces, Polanski made Chinatown and The Tenant, Friedkin made The French Connection, Cimino made The Deer Hunter, Lucas made American Graffiti, George Romero made Dawn of The Dead, Hal Ashby made great movie after great movie, and so on and so forth. In the ‘70s directors could say anything they wanted, however politically or socially charged, and so they did. Everyone but Spielberg.

Spielberg was known as a kind of socially awkward nerd who knew nothing but movies, who cared for nothing but movies, who had nothing in particular to say about people or politics or the world at large, who just wanted to entertain. Watching his films, one is struck by the lack of any thread tying them together outside of one: they all pander to perceived audience needs and expectations. Unfair? Watch his movies. He has a penchant for stories about kids, but is that a thematic thread? Is shooting from low angles as though through a kid’s eyes thematic? You’re reduced to saying that Spielberg makes movies about broken familes, and historical events, and people in difficult situations.

Spielberg’s movies do not take risks. In choice of subject matter, maybe. The Color Purple was a ballsy choice for him, to be sure. But I’m talking about execution. No matter the subject, it’s presented safely, and always with an upbeat, unambiguous ending. There are no ambiguities in Spielberg movies. They are what they are.

And what are they? For one thing, they’re often fantastically well-directed (not always; see Lincoln, Hook, 1941, and, well, etc.). Spielberg knows how to tell a story visually. Even his first theatrical feature, The Sugarland Express, a not very good Bonnie & Clyde wanna-be, is striking for its style, the framing of shots, the way the camera moves. You watch it and think, this kid is going places. From the beginning Spielberg had an uncanny knack for making movies look like movies. Lesser directors put two people in a room and watch them talk, or in the present world of blockbusters let the hyperactive editing hide their inability to direct. At his best, Spielberg lets the camera tell the story. At his worst, he sleepwalks his way through movies not fit for human consumption.

Spielberg’s output is, to be kind, uneven. He’s directed a few winners, and a lot of losers. He also directed Indiana Jones and The Kingdom of The Crystal Skull, for which I happen to believe he should be tried for crimes against humanity, or at the very least be strapped into a movie theater seat, his eyes held open ala Alex’s in A Clockwork Orange, and forced to watch Indiana Jones and The Kingdom of The Crystal Skull on an infinite loop. But that’s a post for another day.

Which brings us to what this post was ostensibly meant to be: a top ten list of Spielberg’s best films. He’s made 27 of them. Surely ten are good? Turns out, no. Take a look for yourself. That’s one grim list of movies. Which is baffling and frustrating. Spielberg is an outrageously talented filmmaker. Ask any director working today, they’ll tell you how Spielberg influenced them. There’s no way around it. He’s the 800 pound gorilla eating nachos in your living room. You’re going to take notice. Yet he keeps churning out these highly polished turds. They make tons of money, they’re hailed as genius, yet the harder you look at them, the more their turdiness is apparent. Turdliness? Turdishness? I’ll work on it.

So the thing is, the ten best Spielberg films don’t exist. I mean, yes, logically his ten best movies exist; there’s necessarily a continuum. But I don’t have ten good ones to discuss. So what we’re going to do here is something a little unorthodox, a little untoward, and probably a little unethical. Hide the children.

I now present for your perusal, the first time ever assembled in one place:

The Top Ten Spielberg Movies About Which More Good Things May Be Said Than May Be Said About His Other Seventeen Decidedly Worse Movies

10./9./8. A.I. (’01)/Minority Report (’02)/War of The Worlds (’05)

See what I mean? This is what we’re reduced to. The godawful sci-fi trilogy of the aughts actually makes the list in a three-way tie for last. What did you expect on here? Amistad? Always? Lincoln? The Terminal? It’s just an endless nightmare of movies you see once and spend the rest of your life trying to forget.

Here’s the thing about A.I.: it was Stanley Kubrick’s project. He never got around to it before having the gall to die, but he did give Spielberg his blessing to direct it. So that’s it—Spielberg resurrected a Kubrick project! That’s cool enough to get on the list, right?

As it happens, no filmmaker is more exactly the opposite of Kubrick than Spielberg in terms of style and sensibility and intelligence and ambiguity and many, many other even longer words, and it shows in the final product. Which actually isn’t completely awful, at least not for the first two thirds. I almost decided I kind of liked A.I. when it seemed to end with the robot kid stuck underwater for all eternity. Only then the wretched voiceover kicks in, and suddenly it’s part 3, and let’s stop right there. Spielberg has since defended himself by reminding everyone that it was Kubrick who came up with the story, including part 3. This is not a good defense. It’s not about the ideas, it’s about the execution. Put it this way: if there were a Kickstarter campaign to resurrect Kubrick and have him remake A.I., part 3 and all, it would be funded to the tune of $300 million in 24 hours, tops (somebody please make this happen).

Also on the plus side for A.I.? Its shimmery, futuristic look, which includes Kubrick’s use of bright light shining in windows from outside, creating otherwordly interiors seemingly detached from the rest of reality.

Minority Report gets points for its look as well. Nothing aside from that, because it is a terrible, terrible movie. Spielberg takes a classic creepy Philip K. Dick notion—what if pre-cogs could see the future and predict murders? What if we arrested people before they killed anyone? Or before they’d ever thought to kill anyone? And what if in doing so, it worked, and there were no more murders? How would that sit with you?—and turns it into a ludicrous Tom Cruise action movie.

The first scene sums it all up: a murder is predicted. The cops rush to the house and get the guy right as he’s swinging the knife. So, yeah, I’d say let’s keep using the pre-cogs, no? No gray area here. Now imagine if the movie had begun with a guy bullshitting with friends at work, when all of a sudden a SWAT team bursts in, arrests him, and throws him in jail. Is that a world you want to live in? A trickier question. Spielberg’s not into tricky questions. Also, there’s a secret bad guy out to get Cruise. Who could it be? I don’t know…maybe MAX VON FUCKING SYDOW? You think? My teeth itch just remembering this dud. This very pretty, expertly shot dud.

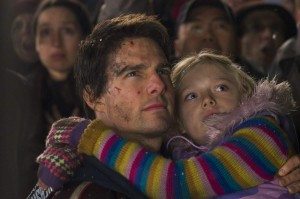

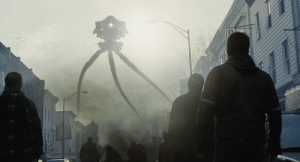

And then came War of The Worlds, in which H.G. Wells’s story about mankind’s hubris and inferiority in the face of superior alien intelligence and firepower, where the human race is saved not through any human ingenuity whatsoever, but by fucking microbes, is turned into an uplifting tale of a man learning to love his children. I mean, my god, if Spielberg made Moby Dick he’d turn it into Ahab re-connecting with his lost father on a G-rated whale chase. Is the extinction of humanity not dramatic enough? The stakes too low? I guess that whole bit about humanity’s hubris and smug superiority wouldn’t play well with Topekan kids.

But the tripods, right? Zapping people into dust? Awesome. It’s the reason he remade it. The original is great. It scared the pants off me as an eight year old. It’s also rather dated. It was crying out for a modern special effects treatment, and that’s what Spielberg provided. Too bad everything else about the movie is so brain-rapingly stupid. Like the scene where Cruise’s kid dramatically asserts his individuality and commitment to saving the world, runs off to fight the tripods, is seconds later engulfed in a massive, miles-wide fireball of death, and then, at the end of the movie, magically shows up alive and well. That is some seriously ballsy having of one’s cake and eating it too. Bravo, Spielberg, bravo.

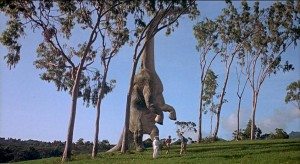

7. Jurassic Park (’93)

I know, it’s not especially good and it’s aged like milk, but at the time it was pretty fun. Michael Crichton knew how to write a decent movie treatment (he called them “books” and published them often), and the conceit of re-creating dinosaurs with their blood trapped inside mosquitos trapped in amber is clever. As for the amusement park island, well, it worked for Westworld, I imagine Crichton thinking.

And dinosaurs! When Jurassic Park opened, no one had ever seen dinos like these. CGI had been brought to a new, mind-blowing level*, and Jurassic Park was the showcase. So that was neat. Of course the best sequence in the movie, the awesome T-rex chase, owes as much to Stan Winston’s practical effects as it does to CGI.

*(It is on record that Lucas was present with Spielberg when they first watched the CGI T-rex running around, and that a tear came to Lucas’s eye at the sight of what was now possible. Just think on that image for a moment. Can you see the Star Wars prequels in that lonesome tear?)

6. Saving Private Ryan (’98)

Starting with the good, how about the opening Omaha Beach landing sequence? Incredible. Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski stylized the battle sequences by stripping the coating off of the camera lenses to create a more washed-out look, and altering the shutter timing such that every grain of dirt and drop of blood stands out in striking detail, a technique borrowed by Ridley Scott and, well, everyone else in the years since. And let’s hand it to Spielberg once again for knowing how to shoot and edit an action sequence such that you know exactly what’s going on. Christopher Nolan might consider re-watching this for some tips.

As for the story, what can you do? You’re in Spielberg-land. It’s overwrought and sappy and, as usual, doesn’t allow you to feel any emotions but the ones being shoved down your throat. Doesn’t war have enough intrinsic emotion not to require the kind of hamminess Spielberg deploys? It’s like he’s never willing to allow the movie to speak for itself. He always has to tell you what it’s saying, in italics, and to throw in a feel-good present-day bookend scene to ensure you leave his violent war movie smiling.

And yet. The battle sequences. The two-man knife fight. The overall look. The movie doesn’t add up, but it’s full of lovely parts.

5. Schindler’s List (’93)

Spielberg’s earlier WWII flick, not to be confused with 1941, though it’s about as funny. I recall being impressed for the first three hours, aside from the expected Spielberg schmaltz getting in the way here and there. It is, after all, a feel-good movie about the Holocaust. Ralph Fiennes does a fantastic Goeth, and Liam Neeson is fine as Schindler. I like how Schindler is introduced in exactly the same way Indiana Jones is in Raiders, showing only his hands, the back of his head, etc., until finally he steps into the light. Indy, Schindler, what’s the difference?

Then there’s the last ten minutes, in which Schindler delivers an absurd, maudlin speech completely out of character, which ratchets up the cheese to unbearable levels. Even now I wonder why any filmmaker would undercut the power of their film in this way, unless it’s for money, glowing reviews, and Oscars. Hmm.

To be fair, Spielberg said he had nobler reasons for making it the way he did. He wanted Schindler’s List to be a kind of monument for Jews who experienced the war, or whose relatives did. It was important to him to have that maudlin ending, and to follow it with color footage of actual Holocaust survivors with the the film’s actors. Which is kind of a bizarre way to end a movie. Spielberg has claimed that Schindler’s List is in a sense a documentary, that it exists as an historical chronicle, which it in no way is. It’s a movie.

Is it a good movie? Overall, sure. I think? It’s been a long time. I saw it once and was never inspired to watch it again. I don’t think I ever got over how the saccharine ending overwhelmed all that preceded it. I just don’t understand that way of filmmaking.

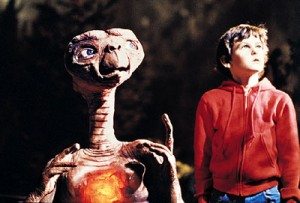

4. E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (’82)

Despite the weirdly redundant title, people seemed to like this one. Go figure. Earlier the same summer Poltergeist came out, which Spielberg produced, wrote the story for, and, some have claimed over the years, directed most of (Tobe Hooper is the credited director; others claim Hooper did all the directing himself). I was 11 at the time. I thought Poltergeist was brilliant—kid eaten by tree! Scary clown! Guy peels flesh off own face!—and saw it at least five times in the theater. E.T. I found to be kind of dopey and overly feel-good. I probably only saw it twice that summer. For me at age 11, not a good sign.

I’ve never come around on E.T., at least in terms of how I personally feel about it. For me, its problems are Spielberg’s problems: it’s overly sappy and manipulative. But I get why others love it. It captures kids and childhood in a way unique to Spielberg, a way many filmmakers since have tried and failed to imitate. (The first half of J. J. Abrams’s Super 8 features an eerily exact replication of “Spielberg kids in ‘82”). In short, Spielberg knew how to portray wonder back then, and showcased it in E.T. far more successfully than in anything he’s made since.

(Update: for a longer, far more positive examination of E.T., go on over here and enjoy)

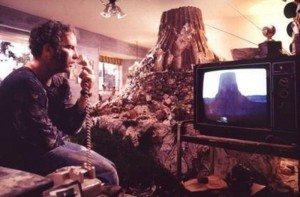

3. Close Encounters of The Third Kind (’77)

If any one of Spielberg’s early movies could be called personal, this is it. He made it after Jaws because, after Jaws, he could make anything he damn well pleased. It was based in part on a movie he’d made as a teenager called Firelight. Many drafts of the script were written by many writers, but in the end Spielberg got sole writing credit.

So here at number 3 we’ve finally come to a Spielberg flick that’s undeniably good. Close Encounters isn’t perfect, but it’s a lot of fun, and it holds up even now. Richard Dreyfuss is great as the obsessed man who after an encounter with a trio of flying saucers is haunted by visions of Devil’s Tower in Wyoming. He leaves his wife and kids behind, and off he goes to see what’s what. Which Spielberg has since said he regrets. It’s rather appalling, now, to watch this father abandon his family, because, like, aliens! UFOs! For Spielberg at that age—and likely for many teenage boys—this seems more than reasonable, but yeah, to present it as Dreyfuss doing the right thing while his wife and kids cruelly hold him back is surprising to see.

The visual effects in Close Encounters still look great. The ships are dreamy, glowing, and unreal, a far cry from the look of Star Wars. And like Spielberg’s other early movies, it’s shot with a real sense of movieness, let’s say, with very thoughtful compositions. Musically, of course, John Williams’s five tone melody used to communicate with the mothership has become as much a part of the cultural background as his score for Jaws.

Spielberg altered the movie for an ‘80 re-release, including a newly shot scene of Dreyfuss actually entering the mothership, but he later realized this was a bad idea. He created another version, the “definitive version,” in ’97, which drops the interior of the mothership and further tweaks scenes. You can watch all three version on the current blu-ray.

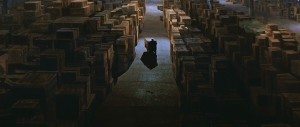

2. Raiders of The Lost Ark (’81)

Finally! Spielberg has made exactly two great movies. Raiders and Jaws. For the purposes of this list, Jaws is #1, but really these two are interchangeable.

Look, here’s the thing. Prior to E.T., Spielberg wanted to entertain, and nothing more. If he had higher aspirations, he wasn’t bothering with them. So while entertaining might well mean having a happy ending as in Jaws and Close Encounters, it didn’t require one. His movies had no messages back then. They didn’t have to be heartwarming and sentimental. Jaws and Raiders are massively popular, fun, entertaining movies, and smart, too. Imagine if blockbusters today could say the same. Imagine if anything at all Spielberg made after Raiders simply aimed to be a roaring good time, instead of tugging at our heartstrings and delivering a Very Important Message, one spelled out in flashing neon letters nine feet high.

So, Raiders. It’s great. You know that. You’ve seen it 500 times, just like me. It’s even better now than when it came out. In ’81, its special effects were state of the art. Now they’re still effective, but they look old. Which is perfect for a movie that’s meant to be a throwback to ‘40s adventure serials. It grew into itself.

There’s nothing sentimental in the whole movie, save the one added-on scene at the end, which in the world of Spielberg barely even qualifies as sentiment. It’s the brief moment where Marion and Indy walk down the steps after his meeting. “They don’t know what they’ve got in there,” says Indy. “Well I know what I’ve got here,” says Marion. They smile and exit. Cut to the scary warehouse harking back to Citizen Kane. The ending is actually ominous. No other Spielberg movie has an ominous ending. Raiders is an anomaly.

Imagine if War of The Worlds had an ominous ending, like the brilliant book it’s based on. That would have been something to see. But the Spielberg who made Raiders was long gone by then.

Everything in Raiders works. The writing, the acting, the music, the tone, the story itself. It was designed to please an audience, with a certain kind of hero, a certain number of action sequences, etc., just like so much of what’s foisted on us today, yet Lucas, Spielberg, and writer Lawrence Kasdan didn’t let those constraints dumb it down. They worked within the model they were inventing to produce a smart movie, a great movie.

Spielberg has progressed as a filmmaker in huge ways since ’81. See the look of his sci-fi, and the battles in Private Ryan. But Raiders was his last great movie. It was the last time he allowed the demands of the film—and nothing else—to guide him.

(Unfortunately, if you’d like to own the new blu-ray of Raiders, you can’t buy it alone. It comes packaged with all three other Indy movies, including the Crystal Skull. For that, Spielberg, you are a giant asshole. By the way.)

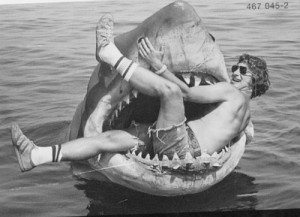

1. Jaws (’75)

Spielberg is a natural filmmaker. He had to be to pull off Jaws, only his second theatrical feature. He may not have known exactly what he was doing, but he did it anyway. The shark, AKA Bruce, failed to work again and again, forcing the movie to focus on Chief Brody (Roy Scheider), Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss), and Quint (Robert Shaw). It’s not a movie about a shark. It’s about an unlikely friendship between three very different men. Who happen to be hunting a shark.

Is there a better scene in any Spielberg movie than the showing off of scars and the story of the USS Indianapolis? It’s not underlined, it’s not italicized. The relationship of these three characters builds to this moment, is cemented by this moment. Spielberg knew enough—or didn’t know enough?—to mess with it in any way. Who wrote the scene? No one seems exactly sure, though all agree it was Robert Shaw who wrote the final version of his monologue.

As with Raiders, the reason Jaws works in a way Spielberg’s later movies don’t is that it wasn’t forced to deliver a heartwarming or simplistically political message. Spielberg’s concern was that it be exciting, that it not be weighed down with subplots, that the characters be at least somewhat likeable, and that it use humor to achieve their likeability. Again, the same kinds of goals he’d use in later movies, that all too many directors and producers have beaten to death since, yet all to service one thing: the movie.

Spielberg set out to make entertaining movies in his early days, with no other agenda. His best movies resulted. I think what happened was this: critics insulted Spielberg by calling his movies merely entertainment. This affected him. He didn’t only want to please audiences, he wanted to please critics. He wanted to win awards. He took the criticisms to heart, and began making movies steeped in family values, social values, feel-good ideals, and sentiment, all delivered with little subtlety or nuance. At first, during the ‘80s, this resulted in various schizophrenic films, e.g. The Color Purple, Empire of The Sun, Always, before he hit his stride with Schindler’s List. Finally Spielberg was embraced by critics. Finally he won his Oscars. His new style was, shall we say, frozen solid in carbonite. He has yet to deviate from it. Until he does, he will never make another great film.

Instead, he will have to suffer untold riches, critical and public accolades, vast fame and power, and a neverending shower of Oscars and other awards. The poor bastard.

Glad to see we feel exactly the same way about A.I. and Minority Report. So disappointing. I never even bothered with War of the Worlds. It has Tom Cruise in it.

Yeah, but Cruise gets sliced in half by a killer tripod! It’s amazing! Or no, wait. He DOESN’T get sliced in half, right, that was it. You’re better off watching the original.

No love for Duel? It’s been a while since I’ve seen it, but I remember thinking it was great…

I do have some love for Duel. But as it’s a made-for-TV movie, I left it out of the discussion. I think I saw it as a teenager. I should check it out again…

I liked aspects of both AI and Minority Report but the endings to both just ruined things.

I agree that AI should have finished with him stuck in the ice although the ending with the robots is still interesting and bit sad and weird.

As for Minority Reports I’ve always said it would have been so much better if he actually killed Max Von Sydow. Although I’ve read some stuff where people argue that the second half of the film is all a dream he is having while in the cryo-prison.

As for people dying, there was some non-descript thriller with Ben Affleck and Russell Crowe that came out a few years back that would have been a much better story if Russell Crowe’s character was killed in the end too.