Take a look at Popeye Doyle. He’s got a hunch.

His hunch says that table is wrong, the one in the corner, the guy with the striped shirt and the tie? Those guys he’s with — mobsters. But who is that guy? The last of the big spenders?

Let’s follow him, Popeye says. For fun. Let’s follow him all the way, no matter what.

Cloudy, Popeye’s partner, allows himself to be dragged along in Popeye’s wake, but he’s investigating the wrong guy. He should be taking a hard look at Popeye instead.

I just watched The French Connection again. Man is that a low-down, grimy, spit-stained picture — and I mean that in the most positive way possible. I mean it adoringly.

From the first few shots, you’re in it. There’s no protection for you at all. Not a shred of sanitization. Everything looks like there was just no time, no money, better things to worry about than a smooth pan or a reset for lighting or a permit to race down the city streets at 90 miles an hour chasing an elevated train.

We’ve got things to do, you got me? We’re with Popeye Doyle and nothing’s going to stand in our way.

If you haven’t seen The French Connection, a) get on that right away and b) you probably don’t know what i’m talking about. This is the non plus ultra of cop films. Fuck Training Day and the rest of that crap they’re giving Oscars to today. William Friedkin’s 1971 masterpiece will take you by the throat. It’s a cinema vérité-style picture that does everything it can to shove you right up against the wall. This is no pretty-boy picture with dashing leads and gorgeous scenery. It’s ugly. It’s raw. It hurts.

If you haven’t seen The French Connection, a) get on that right away and b) you probably don’t know what i’m talking about. This is the non plus ultra of cop films. Fuck Training Day and the rest of that crap they’re giving Oscars to today. William Friedkin’s 1971 masterpiece will take you by the throat. It’s a cinema vérité-style picture that does everything it can to shove you right up against the wall. This is no pretty-boy picture with dashing leads and gorgeous scenery. It’s ugly. It’s raw. It hurts.

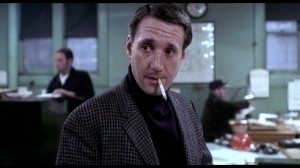

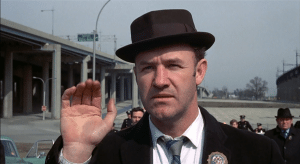

The story is straightforward and based on actual events. Two narcotics detectives, Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) and Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (Roy Scheider) sniff out a big shipment of drugs from France following one of Popeye’s hunches. They try to catch the traffickers — namely the Frenchman Alain Charnier, whom they dub ‘Frog One’ (Fernando Rey), his muscle Pierre Nicoli (Marcel Bozzuffi), and Sal Boca (Tony Lo Bianco) — a New York player and the last of the big spenders.

So why is it so compelling?

Because it’s ugly. It’s raw. It hurts. And it’s true. Not in that “based on a true story” bullshit way, which it is as well, but in the “devastating universal truth of art” way. It is a reflection of us, now more than ever.

These days when the news is filled with stories about the NSA listening in on your phone calls and reading your email; when government-employed goons are paid to peer through your clothing every time you want to get on an airplane; when you regularly sign away all rights to your personal information every time you turn on a computer; when drones fly overhead like armed paparazzi — the dirty truth in The French Connection strikes home.

These days when the news is filled with stories about the NSA listening in on your phone calls and reading your email; when government-employed goons are paid to peer through your clothing every time you want to get on an airplane; when you regularly sign away all rights to your personal information every time you turn on a computer; when drones fly overhead like armed paparazzi — the dirty truth in The French Connection strikes home.

We’re going to follow you all the way, no matter what.

And yeah, maybe we’ll catch a bad guy or two that otherwise might have slipped through, and we’ll book a few lowlifes for picking their feet in Poughkeepsie, but at what cost?

All that comes later though. First we’re on the ground with Popeye and Cloudy, trying to shrug off the Fed who’s riding our ass (Bill Hickman as the miserable prick Bill Mulderig). He’s upset just because the last time Popeye followed a hunch a cop got killed.

In the film, Popeye and Cloudy don’t do anything sexy with ballistics or undercover agents or any of that CSI nonsense. We’re just shaking down sources. We’re sleeping in our cars on stakeouts. We’re standing in the cold, drinking shitty coffee, and freezing our balls off.

Because we’re going to follow you all the way, no matter what. We are relentless and we know we’re right.

Director William Friedkin pulls some swift tricks in The French Connection. Yes, this film looks like it was shot by a surveillance team, but that’s the result of hard work and careful design. The mumbling is on purpose, as are the enveloping shadows, the washed out color, and the ubiquitous grit. That’s not all, though. Within this drearily real aesthetic you’ll catch moments in which directorial mastery focuses attention like Popeye Doyle’s Colt Detective Special: right at the small of your back.

Director William Friedkin pulls some swift tricks in The French Connection. Yes, this film looks like it was shot by a surveillance team, but that’s the result of hard work and careful design. The mumbling is on purpose, as are the enveloping shadows, the washed out color, and the ubiquitous grit. That’s not all, though. Within this drearily real aesthetic you’ll catch moments in which directorial mastery focuses attention like Popeye Doyle’s Colt Detective Special: right at the small of your back.

Take, for example, the early scene in the Copacabana where Popeye first locks onto Sal. It’s a raucous scene, with the Three Degrees singing live, clattering dishes, and overlapping conversations. And then, almost so you don’t notice it, you follow Popeye’s stare to absorb as much of Sal as possible. You’re at the table with him. The surrounding racket is only a distraction now. You can barely hear all the noise as Sal waves his money around.

For Popeye, there’s nothing but the target. Nothing but the chase.

And oh, what a chase! Among the pounding, visceral chase scenes in The French Connection — some breathless on foot, some sly in the subways — stands one of the best chase scenes in any film ever. It is a chase scene that I want to force every modern blockbuster director to watch before they begin work on whichever comic book they’re set to gang rape.

And oh, what a chase! Among the pounding, visceral chase scenes in The French Connection — some breathless on foot, some sly in the subways — stands one of the best chase scenes in any film ever. It is a chase scene that I want to force every modern blockbuster director to watch before they begin work on whichever comic book they’re set to gang rape.

It is unlike any chase scene that you have become inured to. It is said that legendary director Howard Hawks challenged Friedkin to make the best chase scene yet, and Friedkin did exactly that. In a sense — a very real sense — the entire film of The French Connection is one extended chase scene. The particular segment we’re talking about now, wherein Popeye Doyle commandeers a ’71 LeMans and tries to keep pace with an elevated train on the BMT West End Line, is a cypher for the entire film. One relentless man, in a shitty car, chasing a flying subway train, no matter what’s in the way.

Again, Friedkin uses sound to do something counterintuitive here. As Doyle throws himself fully into the pursuit — pounding the steering wheel and horn, flooring it the wrong way down busy streets, screaming bloody murder — we hear little of it. The revving of the engine and the cries of the horn do not place us inside the car with Popeye, as the camera often is.

Again, Friedkin uses sound to do something counterintuitive here. As Doyle throws himself fully into the pursuit — pounding the steering wheel and horn, flooring it the wrong way down busy streets, screaming bloody murder — we hear little of it. The revving of the engine and the cries of the horn do not place us inside the car with Popeye, as the camera often is.

We are down the street, hearing a chase, hearing a train clatter overhead. Maybe safe in our seats, but maybe not. Who knows which way Doyle will swerve in his demand for satisfaction?

Friedkin cuts back and forth between the action in the train and the mayhem on the streets below. When we’re with Popeye, sometimes we’re right beside him, seeing obstacles dart into our path. Other times we’re strapped to the front fender, flying at street level; or we’re a block away tracking the mad shadow of the hell-bent automobile.

This is not a turned-to-11 hash of hyper-quick cuts set to some booming orchestral score to instruct you how to feel. It is pure, throttling need. Popeye swerves to miss a woman with a baby carriage, but if he hadn’t been quick enough, would he have stopped?

No. Nothing stops Popeye Doyle. He will go all the way, no matter what. This is not even the first woman with a baby carriage he’s encountered today — and the other one, I believe she’s dead. Popeye never even checked. Her corpse and orphaned child lie behind him and his quarry runs ahead.

No. Nothing stops Popeye Doyle. He will go all the way, no matter what. This is not even the first woman with a baby carriage he’s encountered today — and the other one, I believe she’s dead. Popeye never even checked. Her corpse and orphaned child lie behind him and his quarry runs ahead.

There is much already written about The French Connection and about this chase scene in particular, so I’ll leave this subject here now in favor of saying something new. To do that properly, I’ll need to discuss the end of the film. If you haven’t seen it, I think you ought to watch it before you read on. Not because there’s a twist in the final moments or a surprising reveal or because the mystery is solved by master detective Popeye Doyle in a show of bravado.

You should watch The French Connection first because your emotional experience of the ending is your own to have and digest, not mine to dictate.

During the final reel of The French Connection, Popeye and Cloudy track Charnier to Wards Island, where the deal finally goes down. Alain and Sal hand over the drugs and receive suitcases of cash in return. The pair climbs back into their Lincoln and, victorious, drive over the convex bridge back to the city. Only reaching the top of the rise do they see the phalanx of police cars awaiting them. Popeye waves. The chase is finally over.

During the final reel of The French Connection, Popeye and Cloudy track Charnier to Wards Island, where the deal finally goes down. Alain and Sal hand over the drugs and receive suitcases of cash in return. The pair climbs back into their Lincoln and, victorious, drive over the convex bridge back to the city. Only reaching the top of the rise do they see the phalanx of police cars awaiting them. Popeye waves. The chase is finally over.

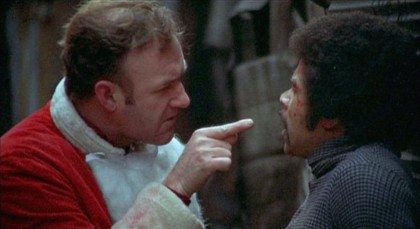

But it isn’t. The chase isn’t ever over. Sal and Alain flee back to Wards Island with the cops fast behind. Sal and the rest of the mobsters hide in one building but Alain runs in the other direction. Popeye, of course, follows Frog One. He stalks his prey through the ruins of an industrial building as Cloudy and Bill spread out, in his wake as always.

There is nothing here but destruction. It is grey, pounded, waste. You can taste it, but Popeye doesn’t even notice. He’s so committed to pursuit that nothing deflects his intensity. Not the state of the world he’s charged into, not even shooting Bill Mulderig by mistake — emptying his gun into the man and leaving him dead in the rubble.

There is nothing here but destruction. It is grey, pounded, waste. You can taste it, but Popeye doesn’t even notice. He’s so committed to pursuit that nothing deflects his intensity. Not the state of the world he’s charged into, not even shooting Bill Mulderig by mistake — emptying his gun into the man and leaving him dead in the rubble.

Cloudy stops then; he kneels beside the fallen Federal agent and reels with the magnitude of what he has wed himself to. Is he still with his partner as he has been throughout, loyally, from the start?

You remember the start, right? When Cloudy got knifed by a penny-ante dealer and just wanted to go home to bed? Then, as always, it was Popeye who pushed him just a bit farther, just a bit longer, just stick it out to the end.

He has a hunch and he’s got to follow it through.

Now, having just put a colleague on the ground, Popeye does not even pause. He just reloads his weapon and races down the crumbling hallway into the darkness after his man. The screen fades to black and we hear, but do not see, another report of his gun. Just a shot in the dark.

End titles reveal the result of Popeye’s investigation. Sal we’ve seen shot dead, trying to escape. The other major players were arrested but served no time. Only the least-guilty member of the conspiracy — the foolish actor who unwittingly carried the drugs into the country (Frédéric de Pasquale) — went to prison, and him for only 4 years.

End titles reveal the result of Popeye’s investigation. Sal we’ve seen shot dead, trying to escape. The other major players were arrested but served no time. Only the least-guilty member of the conspiracy — the foolish actor who unwittingly carried the drugs into the country (Frédéric de Pasquale) — went to prison, and him for only 4 years.

Alain Charnier got away entirely. Never caught. Never found.

And so The French Connection is a chase movie that doesn’t end. It is not about the successful arrest of a major international drug smuggler, or the busting of a narcotics ring. It is the story of Popeye Doyle, a good-intentioned man corrupted by relentless pursuit.

While Gene Hackman is absolutely brilliant in this role, this is not a part any man should aspire to play. Yet this is the role that more and more of our national security apparatus finds itself stepping up to assume: looking at the world as nothing but potential targets. Like Popeye, they stroll into the club and do not taste the whiskey, or hear the band, or comfort the injured friend. They seek out the ones who look wrong and chase them to the end, regardless of who gets hurt along the way.

Sure. I’m positive that the NSA and the PRISM program and other initiatives like that catch and stop some criminals. Fifty acts of terror according to Keith Alexander. I’m equally positive that they do so with all the delicacy and consideration of Popeye Doyle.

Remember the last time you had a hunch? A good cop died.

What has your investigation cost us in money, in ruined lives and to what benefit?

You can say that only people with something to hide need to care about privacy, but give me your passwords and I’ll find something you’d rather I didn’t in under an hour. And I’m not a racist, reckless detective with nothing to fill my life but you and your potential criminality. It isn’t my job to read your Tweets and decide whether or not you’re kidding about bombing a plane.

I watch The French Connection and this is where my head goes today.

What would have happened if Popeye had gone to a different club that night, or been less driven? All that heroin would have hit the streets, but I don’t see anyone claiming this or any other drug bust cleaned up the streets for good — not in New York in the ’70s, that’s for damn sure. Other than that? Sal and Pierre would have lived. And so would the young mother who was shot when Pierre was firing at Popeye. And the cop on the train. And the conductor. And Bill Mulderig.

So yes; due to the efforts of dedicated law enforcement personnel, crime has been thwarted — but have you seen the bill?

That’s the dirty truth of The French Connection. There’s no happy ending. Just a reminder of what the world becomes when everyone turns into a potential criminal.

And in case you’re confused, your role in this is Cloudy’s. If you’re tired, hurt, had enough: say so. Someone — Popeye’s friend — should tell him to stop before someone gets hurt.

Have a nice day.

I loved this post. I watched this years ago, might have to watch it again now. I really love Gene Hackman. It’s strange to think that he was a proper big time movie star in the 70s, not just a character actor movie star. I’m not sure who his equivalent would be.

He would have been relegated to police chief or something if this was made today. Channing Tatum or Gerard Butler would be Doyle but the character would be called Hercules not Popeye.

Thanks Mash. French Connection is most definitely worth repeat viewings and Hackman is one of my favorite actors. There are actors like him today, but it’s harder to make films starring them. Check out The Visitor starring Richard Jenkins for example. It’s not French Connection, but it’s definitely worth a watch.

Interestingly, the whole anti-hero thing is back thanks to Batman and Christopher Nolan. This new crop doesn’t seem to understand what an anti-hero is, though. It’s not that your hero is dark and misunderstood. It’s that your hero is actually the villain. In the Dark Knight, Batman is really the NSA and the Joker is Anonymous. Outside of being willing to kill a ton of people… Joker’s goals and beliefs make a lot more sense than what the Bats’ is fighting for. Remember when Batman hacks everyone’s cellphone to find one criminal? Yeah. Good times.

Good post. Just finished watching number 2 today but watched number 1 again a few weeks ago. Loved the gritty realism of these films, particularly no 1. Have to say though I disagreed with your conclusion (though you did in fairness make a bunch of different points). I don’t think Popeye is an anti-hero as such though I do think he stands for something. That thing is power. The power to achieve something (or catch someone in his case) when the person (in your words) is relentless in his pursuit of the goal.

The reason the EL train scene is so powerful is because doyle is almost superhuman in his effort to catch the man. Almost every flip of the camera contains a near fatal accident not only for Popeye but for others too. It would seem impossible to me for someone to keep up with a train going at top speed in a car underneath it in full traffic. But he does. The same way he eventually nails charnier at the end of no 2. There’s no nonsense about it. He just calls his name. He has only one shot and takes it and gets his man (though yes acknowledged that he does actually shoot twice). I take a lot of lessons from these movies. Namely that the guy who works harder than the other guy and is prepared to take more pain will win. It is an irrefutable fact of nature. Indomitable will wins every time, no matter how suave or sophisticated your opponent…

Thanks Nick. Glad you liked it.

I think you’re conflating the take-away from FC2 with what Friedkin was showing in the original. The second, while decent, is a typical sequel in that it takes established material and legs it out in any direction available. And Popeye gets Charnier in FC2, because it’s about something completely different than FC.

Where you see near super-human ability in Popeye’s chase with the EL train, I see complete disregard for safety — his, or anyone else’s. Remember: before that chase begins the assassin shoots down a woman pushing a stroller. What happens to her? Her abandoned baby? No one ever bothers to ask, certainly not Popeye. He doesn’t care about her death, or her baby’s cries. He only cares about his relentless pursuit. Same when he kills Bill Mulderig. He just plows on, regardless of consequence.

He isn’t superhuman; he’s subhuman. He is all Id. He is more destructive than that heroin will ever be.

If you take a lesson from the French Connection, I hope it’s to reconsider what ‘winning’ looks like. Indomitable will is powerful stuff, but if there’s one thing Doyle never is in either film, it’s happy.

Evil I think you’re conflating the hero with the villain here (and charnier and frog 2 most certainly are the villains in this story). Maybe the 70s were a different time but things were certainly more simple back then. Not sure how old you are (I’m 40 so have little recollection of it) but Popeye reminds me of my old man in some ways (both my parents were from NY though we don’t live there anymore). There’s just no bullshit with these characters. It’s kind of a NY attitude. They want something and they just go after it, no matter what it takes.

I guess you see the dangers and perhaps the human cost both to characters like Doyle and those who come into contact with them but I see it as inspirational. Remember that it wasn’t Popeye who shot the mother by the pram (and Mulderig doesn’t really deserve much sympathy either as he was kind of a jerk). To say that Popeye “is more destructive than heroin will ever be” is just plain crazy with all due respect. I’m sure charnier’s heroin probably killed scores of people (yes, actually killed, not near misses). The only way to take these scumbags down is with “relentless” determination and if there were not more guys like Popeye around I’m sure we’d all be swimming in a sea of shit.

But look around Nick. There are plenty of people like Popeye around and we ARE swimming in a sea of shit because of it. That’s the reality that this post describes.

Essentially you’re saying that the NSA should have complete access to your communications because that’s ‘relentless’ and how to win. And that the war on terror is bound to end up victorious because it’s relentless.

There are people who believe that, and perhaps you’re one of them, but there isn’t a chance in hell I’m going to agree with you — or that Friedkin did.

You can say that FC is about ‘taking these scumbags down’ but that’s not accurate. FC2 may be about that, but to apply the sequel’s message to the original film and to pretend they are saying the same things is a strange sort of logic. At the end of The French Connection, Charnier gets away clean. Only the small fry get caught and only the least of them, at that. You don’t like Mulderig, and he is a prick, but because of Popeye he’s a dead prick — not Charnier.

What does Popeye accomplish? He keeps one load of heroin off the streets. That’s it. The drug trade continues and its architects escape punishment.

I said ‘Popeye is more destructive than THAT heroin will ever be.’ Count the bodies in the film, of completely innocent people. Don’t just see them as background and forget them because you want to like Popeye.

You want to make Popeye into a hero, but only because you’ve seen FC2 and that has an upbeat ending. Thing is: that film is wholly fictional. The original isn’t. So if relentless pursuit is the aspiration, it is only the goal in fiction. In reality, it leaves us swimming in a sea of shit.

You are frightening me, Nick. Popeye is not a hero.

How pleased with Popeye’s determination would you be if while shooting at his target he gunned down your wife/child/mother/whoever is most important to you? Would you say, “well, but he was after a scumbag, so good for him”? Maybe you would. Seems merely being a jerk earns one a death sentence in your world.

I can’t imagine what it means to say the ’70s were more ‘simple.’ As far as movies go, characters were often far more complex than they are in movies today. It was the era of the anti-hero, and Popeye is a prime example.

Yes but it wasnt popeye who shot these people! He gunned down Mulderig but he didnt mean to. It was a mistake. You guys are shifting the actions (and culpability) of one person onto another. I think when people say that popeye was a sort of anti-hero it was in relation to the heroes in 60’s movies like John Wayne, all-American types who saved the world. Popeye on the other hand swims in the gutter every day and gets the job done. He’s still a hero but just a different kind of hero. A gritty determined one who isnt afraid to get his hands dirty. He doesnt make things look easy peasy.

In relation to the point on the NSA, I’m not really sure where that comes from to be honest with you. To me there is absolutely no connection between the NSA snooping on millions of emails in the name of some undefined “war on terror” (which methods I also disagree with FYI), and popeye doyle’s role (and legacy) in this movie. He’s an excellent cop. A bunch of mobsters sitting at a table with one who spends (extravagantly) more than the others who is not known to the police. I’d say that’s worth a hunch.

Anyway I just cant agree with you guys on this. I’m a huge fan of 70s movies and often identify with the values in these movies as they are real human values without the gloss and other crap you see in movies these days.

Popeye doesn’t get the job done in The French Connection; that’s the entire point of the film, which you have successfully and repeatedly missed. Congratulations?

And please re-read your above comment if someone accidentally harms you. If it was only a mistake, it doesn’t count.

Again, you are missing the point of the movie. It isnt about whether he actually catches charnier or not, its about (as you put it yourself) the pursuit. Its like anything in life. Dont worry too much about whether you get covered in glory in life because often you wont. Its more about giving everything you’ve got. And that’s popeye doyle through and through. Its also 70s movies through and through. They’re not afraid to show you how it really is. Something a lot of movies these days just dont do….

Friedkin says:

“The Charnier character in The French Connection is a much more admirable human being than Popeye Doyle. That’s the thin line between the policeman and the criminal, and between good and evil.”

I’m glad you have strong opinions. I’m less glad you’re unwilling to challenge them.

Now, I believe there is nothing further I can do for you. If you wish to discuss this further, just re-read what I’ve already written but add in more exclamation points and imagine me saying this stuff with increasing exasperation and mounting concern for your sanity.

Let me give you some advice if I may sir. You should always look at art with an open mind as everyone has different takeaways. Like looking at a picasso. The artist may say that he painted a picture to capture a particular thing but may end up capturing something else. If you are talking about Friedkin’s view of this movie, the first thing that he says is that it is “an impression of that case”, ie his impression. His portrayal may create a different impression to the one that he believes he saw, particularly if he paints it in its absolute truth with no gloss, as I believe he did here. Friedkin also says about Egan and Grasso (the two real-life cops who are the subject of the movie):

“When I met them and actually went out with them on some of the narcotics busts they had pulled off, I could see that they were not only the two most effective cops in New York, but that they were having a lot of fun doing this.”

Friedkin states the above notwithstanding his portrayal of egan as an “obsessive, brutalizing racist”. Basically, the guy is complex and it is far from a black or white portrayal.

You’re a smart guy Evil and I liked your original post though you came to the exact opposite conclusion to me. As someone who reviews movies (and I havent read any of your other reviews on this site), you should avoid seeing things in black and white and coming to “right or wrong” answers as its rarely that clear. If you cant see that then you shouldnt be reviewing movies in the first place.