Hal Ashby was an immense, intuitive talent who drew indelible lines across the throat of our culture. He’s one of my favorite directors, but his career was brief. He left us with only 11 feature films.

Many of those films you call your favorites.

Many of those films you call your favorites.

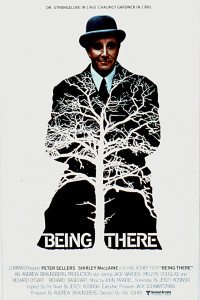

Harold & Maude, The Last Detail, Shampoo, Bound for Glory, Coming Home, and Being There all came on each other’s heels, an unbroken string of humanistic, insightful character dramas. Time and again he showed us recognizable individuals undermined or enlightened by their own strange devices. His films leave you uniquely introspective. That was his gift.

Then, the story goes, drugs took their toll. After Being There, his film Second-Hand Hearts languished for two years in editing and landed with a thud (it is only available again as of this March). Next Ashby shot Lookin’ to Get Out.

That film suffered a similarly depressing fate.

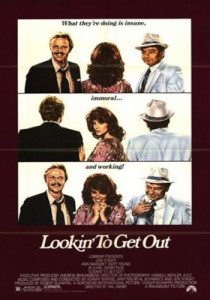

Lorimar and Paramount Pictures wrestled the film away from Ashby, recut it, and threw it at the wall like a wet lump of toilet paper. If you check Rotten Tomatoes, you’ll see Lookin’ to Get Out commands a disheartening 25% approval rating.

Lorimar and Paramount Pictures wrestled the film away from Ashby, recut it, and threw it at the wall like a wet lump of toilet paper. If you check Rotten Tomatoes, you’ll see Lookin’ to Get Out commands a disheartening 25% approval rating.

Those critics are reviewing the wrong film.

Literally, the version of Lookin’ to Get Out that you can watch today is a different film from the one that played in theaters. This newly released version is vintage Hal Ashby. And so is the story of how it comes to us.

Lookin’ to Get Out first sprang from a script actor Jon Voight brought to Ashby — they had previously worked together on the Vietnam veteran drama Coming Home. Voight collaborated with novice screenwriter Al Schwartz to write this tale of tough-luck gamblers and also starred in and produced the film. Ashby directed in his usual ethereal fashion and began to edit it as well.

During post-production, however, Ashby fell into conflict with the studio. The film was wrestled away from him and recut to be more commercial. When it was released, critics and audiences hated it, calling it tone-deaf and only slightly better than the reviled Second-Hand Hearts. It was a continuation of Ashby’s downward spiral.

As if he were a character in one of his films, his flaws got tangled up with his talents and left him bereft.

The ghastly reception Lookin’ to Get Out received was equally painful for Voight. He had sunk considerable emotional investment into the film and received only disappointment in return. That was 1982.

Twenty-five years later, Voight met Nick Dawson. Dawson was writing a book about Hal Ashby and he told the actor how much he loved Lookin’ to Get Out. Voight was startled to learn that Dawson had seen a version of the film he hadn’t known existed. Together they went to UCLA, where they screened the university’s mysterious print. From the opening shots, it was clear this version was significantly different from the panned theatrical release.

Hal Ashby had secretly re-edited the film before his death in 1988. He never told Voight or any of the other principals — and that’s the thing that makes my heart crack and sing. Ashby knew what he could do and he did it, not to impress anyone, but only to overcome.

When he finished his work, he quietly donated the print to UCLA. Instead of the failed comedy that had been released to the detriment of Ashby’s reputation, the students at UCLA had been watching the film as originally envisioned.

That version has been widely available only since 2009. And, as edited by Hal Ashby, Lookin’ to Get Out is quite good.

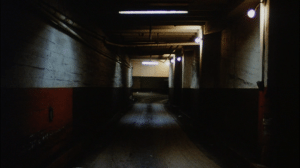

From its opening scene, Lookin’ to Get Out sets forth the situation. We see the dank gullet of a parking garage. Inside — wrestling with his impulsive, destructive instincts — Voight’s Alex Kovac reclaims his ridiculous white Rolls Royce. It barely runs, but Alex is on a high, spreading money around like the last of the big time spenders.

He’s a gambler and he’s won big. Before the sun rises, though, he’ll lose it all, have his car defaced, and go back in the hole another ten grand — money he’s got little chance of being able to pay off. Alex goes home to his friend and roommate, Jerry Feldman, and tells him what a good day he had: yesterday.

That is Lookin’ to Get Out.

That scene — Jon Voight and Burt Young — takes two terribly flawed men and winds them together like rope. Alex and Jerry stick together as tonic to the trouble they bring upon themselves. Threatened by the men Alex owes money to, they flee to Vegas, dreaming of winning enough to earn another good day. They are looking to get out.

Watching the film, it’s hard to like to Alex. Voight plays him like a man whose organs drip meth. He’s full of grating laughter and forced joviality until his suppressed rage wins out. He is exaggerated in the same fashion as Bud Cort and Ruth Gordon’s title characters in Harold & Maude. While we may not believe people such as these actually exist, that doesn’t keep us from relating to the honesty in their experience.

Burt Young’s Jerry is easier to keep company with. He is a stunted man unable to rise above his base needs. Primarily, those involve sex, but not in a tawdry way. You get the sense that Jerry is too simple to handle raw love. Instead he needs to take his comfort in less sophisticated doses. If Jerry does love at all, it’s Alex to whom he keeps true.

In Vegas, Alex and Jerry allow a misunderstanding to lead them into grand swindle of comfort and hope. A good day, as long as it lasts. They are comped as high-rollers and foolishly extended a generous line of credit. Ann-Margaret steps in as Patti Warner, an old flame of Alex’s who reflects his choices back at him. And the rest of the film follows the trio as they go up and down, left and right, attempting to escape what they ought to cling to.

Sometimes winning is knowing when to hold.

While you might expect this to be a story about gamblers who eke out that one big win, it is and it isn’t. It’s a story about Alex and Jerry, two men flawed in the Hal Ashby style. Without each other, they are all Achilles heel. Together, the sinew and tendon barely manages to hold.

I watched Lookin’ to Get Out expecting not to like it, but I did. Rumors tell of Hal Ashby spending six months cutting a sequence of the film to Message in a Bottle by the Police, but that’s not in this edit. Instead there are other long, music-driven sequences that carry the characters forward. There are beautifully composed shots — filmed with the assistance of cinematographer Haskell Wexler — such as one in which Alex and Jerry pillow fight in their ridiculous penthouse suite. Another closets Jerry and a thug in a bathroom stall and lets us peep through the crack in the door.

Twice in the film Ashby adds in prolonged action sequences and neither works. They try to split the difference between the conflict and the comedy but feel forced. Ann-Margaret anchors a solid supporting cast of character actors, including the excellent Bert Remsen, but the world of the film doesn’t quite gel. The story swings between farce and tragedy in a way that’s hard to digest. Locking onto the relationship between Alex and Jerry saves the day, but much of the rest feels ungrounded.

Lookin’ to Get Out is not a brilliant film. It is a troubled picture with a solid core. Like you often see with directors’ freshman efforts, there is a sense here of something greater that didn’t quite spring to life. Having not seen the theatrical release, I can’t say how this version compares. I can say that I’m glad I saw it. It is leagues better than 8 Million Ways to Die — Ashby’s last theatrical feature — and easily as good as his first, The Landlord.

If what you want is to join Hal Ashby in investigating the human condition; here you go.

In the end Lookin’ to Get Out will surprise you. It is not the film you expect and it doesn’t wrap up all Hollywood. It is the story of a good day: yesterday. It’s the story of what we leave on the table in our hurry to be somewhere else. Like it or not, you might recognize yourself in Alex and Jerry.

If so, take your time thinking about why. What Hal Ashby sees and reveals has honest value. Hold on to it.

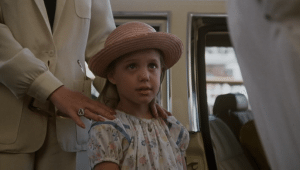

I also would be remiss in not pointing out what seems to be for many a foolish high point of the film. Towards the end, a six-year old girl comes on screen for a brief scene. This is Voight’s daughter, Angelina Jolie, in her film debut. At the very beginning of the film, Alex also has a conversation with a woman in a Jeep. This is Jolie’s mother, Marcheline Bertrand.

Originally, the script called for the child — an estranged son — to be a boy. Ashby insisted it be a girl and thus Jolie. If you want to know why, ask Ashby’s daughter, Leigh McManus.

Despite Hal Ashby’s intentions, he never knocked on his daughter’s door. They never met.

Interesting. Never knew about the secret edit of this. Will definitely check it out.

You should. There’s a lot to appreciate in it and it creeps up on you in the hours after it ends.

This is a great article – the idea that the Police could have been the score to the film is crazy…. I have a feeling that if they had been Lookin’ To Get Out would be remembered at least as “that movie with The Police score”.

You didn’t mention him in this overview, but I’ve always been fond of the character Richard Bradford plays – “Bernie Gold”.

Glad you liked it Ben. It’s been a long while since I watched this one. Remind me about Bernie Gold?

He’s the white haired casino owner who Ann-Margaret is dating. Really chews the scenery in the climax fight in the casino – the actor has been in a lot of stuff through the years.

It’s always interesting to me that the casino they filmed this in – the MGM Grand – had a massive fire that nearly burned the place down a month or so after they wrapped production.

Apparently when he first started filming at the casino Ashby mentioned that there weren’t many exists – that certainly changed after the fire!

I’ll have to watch it again. I’ve learned a bunch about Ashby since I wrote this and would like to reassess. Check out the comments on our post on Second-Hand Hearts for some interesting stuff…