Are you a woman? Do you want to make a man do your bidding? There’s one sure-fire, time-tested method for success. Spread your legs for him. Or, better yet—don’t spread your legs for him. Or spread your legs once, and promise it’ll happen again…after he’s done whatever it is you want him to do. So long as your legs are in the conversation, you can make him do anything. You can make him bark like a dog, or whistle like a gnu, or stand on his head, or drink champagne from your shoe. Or maybe write you a poem in the style of Dr. Seuss. For example.

You can also make him give you all his money, promote you, and kill your rich husband. In the world of film noir, these are usually the most popular options. Women in film noir know what they want and know how to get it. There’s no stopping them. If you fall in love with one of them, you’re at their mercy, of which they have none. You’ll imagine you’re in charge. After all, you’re the man, right? Wrong. You aren’t the man. You’re not in charge. You’re a chump, and more often than not, you’ll wind up dead or in jail.

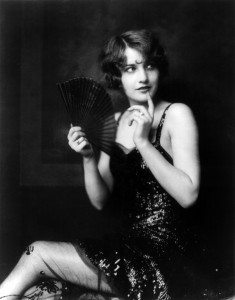

Barbara Stanwyck excelled at playing powerful women, some highly noirish and manipulative, others kind and loving, but never once did she play a doormat. She had an air of modernity about her. And she was popular as all get out. By 1944 she wasn’t only the most highly paid actress in the movies, she was the most highly paid woman in the U.S.

For this week’s Mind Control Double Feature we plunge deep into the noirish depths of sex, money, and murder, with Stanwyck as our guide.

Baby Face (’33)

Welcome to the world of pre-code Hollywood, the era of the early ‘30s when, despite the existence of a self-imposed moralistic production code, no one paid any attention to it. This is when the first gangster films thrived. Sex and violence were big in the early days of the Depression, not to mention politics. You could get away with almost anything.

Baby Face is one of the pre-code greats. It’s a simple story of a girl from the sticks making it big in the city. Stanwyck plays Lily, who works in her father’s speakeasy in Prohibition era Erie, PA. She serves alcohol. Oh, and also her father whores her out to the customers, beginning when she’s 14. After dad dies in an explosion, she’s at loose ends. Fortunately, one of her customers, a philosopher, reads her a passage from Nietzsche for inspiration:

A woman, young, beautiful like you, can get anything she wants in the world. Because you have power over men. But you must use men, not let them use you. You must be a master, not a slave. Look here—Nietzsche says, “All life, no matter how we idealize it, is nothing more nor less than exploitation.” That’s what I’m telling you. Exploit yourself. Go to some big city where you will find opportunities! Use men! Be strong! Defiant! Use men to get the things you want!

Well, truth be told, you couldn’t get away with everything in ’33. This speech was altered when the movie first came out, softened a bit. Lucky for the world, the original cut of the movie was eventually re-discovered, and that’s the version now available.

So Lily and a girlfriend jump on a freight train headed to New York. But they’re caught by a railroad man. He’s about to call the cops when Lily says, “Can’t we talk this over?” Sure they can. If by “talk” you mean “screw.”

In New York, Lily walks into an office building to get a job. The man hiring asks her if she’s got any experience. “Plenty,” she says, and leads him to a back office.

The best gag in the movie is how every time Lily gets herself a promotion, the camera pans up the outside of the office building, one floor at a time. She literally sleeps her way to the top.

Her romantic entanglement become ever more entangled, as happens. Trouble ensues. There are pledges of love, engagements broken off, murders and suicides. You know, the usual.

Will Lily ever find true love? Does she want true love? Is there a happy ending? You’ll be left guessing until the end.

Baby Face is hugely entertaining. It’s amazing to see sex treated so bluntly in a movie from ’33, with a female character so unapologetic about the power she wields. These days, the only women as powerful as Lily are the ones in action movies, shooting people left and right. Lily doesn’t need to fight anyone. Sex and brains are all she needs to get her way.

Double Indemnity (’44)

Best film noir ever? One could make the argument. There are seedier noirs, weirder noirs, noirs more in the B-picture realm they most ideally occupy. So let’s call Double Indemnity the most perfect noir.

It’s directed by Billy Wilder, who six years later would make another contender for best noir ever, Sunset Boulevard. It’s based on a book by James M. Cain, but Raymond Chandler wrote the screenplay with Wilder, and tossed out most of Cain’s dialogue. It’s a rare example of the movie far outshining the book it’s based on.

The story is prototypical noir. An insurance salesman meets a rich woman who hates her husband. Not that the husband is in any way a bad guy. He’s merely inconvenient. She sounds out the notion of his dying in an “accident,” thus triggering the double indemnity clause on his insurance policy and paying out twice the money.

The salesman is Walter Neff, played by Fred MacMurray as a kind of nice-guy heel with very iffy morals. The woman is Phyllis, played by Barbara Stanwyck with a smoldering, lascivious evil. Wilder purposely had her wear a bad wig and too much makeup. She’s a fake beauty on the outside, and empty on the inside.

Neff has no interest in her plan at first. But she makes it worth his while by throwing herself at him. He’s a sucker for a pretty dame. He actually believes she loves him.

They carefully plot the murder. It’s going to look like an accident. Neff knows exactly what claims adjusters will be looking for if they suspect foul play. He knows the pitfalls to avoid. With their plans set, they embark on the killing.

But there’s a problem. Walter’s friend and coworker, Barton (Edward G. Robinson), has a gut feeling something’s not right. He suspects murder.

And that’s only part of the story. There’s a daughter, a past husband, a mysterious lover. It’s all very naughty. Unlike the carefree days of Baby Face, in ’44 the Production Code was in full effect. There was a lot of trouble getting approval for Double Indemnity, but Wilder won out in the end. After all, the protagonists get exactly what’s coming to them.

John Seitz is the cinematographer. He fills the frame with shadows and strips of light implying prison bars. As with all noir, the look is inspired by German expressionism. It’s stark and creepy.

With Chandler on board, the dialogue is snappy as hell. Check out this scene, shortly after Neff first meets Phyllis:

You don’t want to mess with Barbara Stanwyck. I mean you do, more than anything in the world, but you’re going to pay. You’re going to pay with everything you’ve got.