There has been a lot said lately about the state of modern cinema. Steven Soderbergh, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and even Gore Verbinski have come out, heads all scratchy, to wonder how filmmaking can survive the onslaught of movie marketing madness.

Today, studios want films to appeal to everyone around the globe. They want all those people, wherever they live, to buy a ticket and a Blu-Ray. In order to actualize this reality, they are making more and more hyper-expensive films that depend increasingly on visual effects, which require no translation. They are also marketing the living hell out of everything.

The other day I dared to offer an opinion in one of the internet’s less hospitable comment threads about my reactions to the marketing for Guillermo Del Toro’s upcoming film, Pacific Rim. I was told in no uncertain terms that it was dastardly and foolish to judge a film — particularly a film’s story — based on marketing.

Is it, though?

This concept — that trailers and posters and websites are to films what covers are to books — is the kind of thing that people voice with certainty. It makes them feel good to say it, and it sounds righteous and true.

“We don’t pay attention to ads. We only watch films.”

Now, in the first place, I hadn’t judged Pacific Rim based on the marketing. I’d readjusted my expectations based on the information presented to me in trailers. I still plan on seeing Pacific Rim. I just now expect to see something more like Transformers and less like Hellboy or Pan’s Labyrinth. I expect a film built around effects and not around character.

In the second place, a film’s trailer is not analogous to a book’s cover. One doesn’t compile the cover of a book from elements of the actual book. A cover is just one artist’s interpretation of what the book contains — whether or not the artist even read the book in the first place.

Judging a book by its cover is pretty foolish. Using a book’s cover to gauge your interest in the book is only slightly less foolish.

We can no longer say the same thing of marketing materials for modern films.

I am no expert on film marketing. I do know, however, that marketing budgets frequently match or even exceed a film’s production budget. When we’re talking about massive summer films, the marketing campaigns are planned out with the same degree of seriousness with which the film’s script is written. (That is actually being generous to the scripts of many of these films.) Marketing campaigns are multi-month assaults of data designed to build buzz and sell tickets. The film itself is almost ancillary.

Are people really telling me — somewhat pretentiously and condescendingly I feel — that I should ignore the information delivered through marketing? Frankly, I think that’s idealistic and less than perfectly sane.

Being generous, I accept that there is a distinction between ‘judging’ a film based on marketing and ‘reassessing expectations’. Quibbling over semantics isn’t too useful, but I’m pushing back against an idea that stakes a wide claim. People tell me to ignore movie marketing because it’s “meaningless and counterproductive.” That’s a definitive and inflexible statement.

I wouldn’t tell you that a film is horrible if I hadn’t seen it, but I don’t see a failure in reasoning in deciding not to see something based on the known facts. Particularly when those known facts are delivered to me by those with the most to gain from me coming to the opposite conclusion.

Let’s look at Pacific Rim. Ages ago, I heard that Guillermo Del Toro — a director whose visual style I appreciate — was making a film about giant monsters that emerge from the Pacific to face off against giant robots. I thought: good. I will see that film.

Then, much more recently, trailers began to appear. I watched the first one and then completely forgot that I had seen it. There were some cool looking giant monsters. There were some big robots. These things hit each other with ships while Idris Elba gave an impassioned speech about canceling the apocalypse.

Maybe Del Toro was involved in cutting the trailer, maybe not. He definitely shot all the scenes the trailer contained, though. It isn’t some artists interpretation of what the movie contains; it’s scenes from the movie.

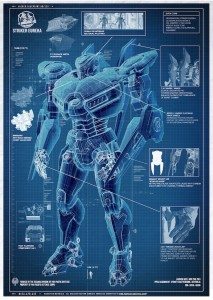

When the second trailer and additional marketing material came out months later, I saw some of that stuff and remembered the first trailer. There didn’t seem to be too much different here. More monsters maybe. A lot of supporting marketing material explaining the schematics of the robots or how the mind-meld whatever works that allows two pilots to operate one robot. Deep background stuff that exposed the complexity of the monsters and the machines. A lot of squee about the admittedly interesting and well-developed production design.

And Idris Elba canceling the apocalypse as Ron Perlman backed away slow from something.

What did I learn from these marketing materials (only some of which I looked at)? I learned that Guillermo Del Toro’s visual style was in full effect. The monsters did look cool! I also learned that whatever else was going on in the film, what the marketing team felt was most salable was giant robots hitting giant monsters. Action scenes which translate into any language without a single subtitle.

That wasn’t surprising, but was disappointing. It’s not the kind of impression I got from the advertisements for Hellboy, which I love, or Pan’s Labyrinth, which I love less than everyone else.

It took me a while of not thinking about it for me to understand why I felt no emotional pull to see Pacific Rim: There seemed to be no people in it.

Nothing I was shown told me who I was supposed to empathize with or why. The world is under threat. We need to save the world. Send the robots to hit the monsters with ships. But what do I care if the world ends? If this was the 1970s, I might have some concern that at the end of Pacific Rim, the monsters might win, and then I’d feel tension and empathize with the film’s world in an abstract way. In the 2010s, forget it. The robots will win.

So there’s nothing to care about. No plucky pilot who just wants to save his mother from a lifetime in the box factory, no commander who needs to prove his mettle in order to overcome his fear of gelatin-based desserts, nothing.

Does that mean the film has no character in it? No. Not at all. It means none of that made it into the marketing. From that, I extrapolate that there is nothing particularly distinctive or salable about the characters. If there were, then why not introduce that via marketing so that people can enter the film predisposed to relate to Secret Space Pilot Narvin Pupik and Commander Lydia Loo?

They had plenty of money to spend; could none of it have gone to character introductions via some of that auxiliary marketing materials?

There are a few possible explanations, of course, for how the film might be strong in character while none of that has come through yet. Perhaps the character stuff is too complex to be easily encapsulated. Perhaps the marketing team just felt the robots and monsters would sell better. Maybe they forgot that people relate better to other people than they do to giant robots with arm swords.

I don’t feel I’ve judged Pacific Rim for not having any characters. I have looked at the data presented to me and asked questions and readjusted my expectations accordingly. That’s called being a human being. It’s how our brains work and for the most part I’m pretty happy with it.

This week, the marketing team for Pacific Rim released a trailer that focused more on the people. Obviously, I was not the only person to feel a lack of humanity in the advertisements.

This trailer showed us a reluctant pilot (Charlie Hunnam) called to save the world by Idris Elba. He joins another pilot (Rinko Kikuchi) via neural-handshake to so they can drive the giant robot. Neither pilot is named in the trailer. Kikuchi gets no dialogue (though she was great and silent in The Brothers Bloom). There is a shot of conflict between the robot operators. There is a shot of celebration. We are told that the stronger the bond between pilots, the better they fight. And then it’s the same stuff of digital objects hitting each other with other digital objects.

That’s the response to a reasonably widespread backlash against a lack of character.

Do you still think I shouldn’t re-evaluate my expectations of Pacific Rim based on its trailers? Even though that is precisely the purpose for which they were made?

I will go to see Pacific Rim because I like Del Toro. I will go because I like giant robots and giant monsters. I will have some minor hope that beneath the effects there will be some sort of story — not concept, mind you, but actual story — that engages me. I will hope that there is character, that those characters have personalities. I will watch it and then I will judge.

But if I decided not to watch it based on the movie marketing, that would be reasonable. To say otherwise is to delude yourself as to how and why movies are made today.

You can’t always tell about a film by its marketing. The converse is simply not true.

Sometimes — frequently even — the marketing is the movie. It is a professional’s selection of the best parts assembled in a manner designed to appeal to the widest possible audience, regardless of consequence or accuracy. So if you don’t find these advertisements exciting or funny or compelling, drawing your own conclusions is just part of the game.

Not only that, but bear in mind that with ALL major releases of this sort, marketing doesn’t come in at the end. Marketing is there from the start. If the marketing team doesn’t know how to sell a movie, the movie doesn’t get made. They are, sad to say, the most important element of any major movie. Pacific Rim was green-lit, like they all are, because the studio knew how to market it. It was written to match the marketing plan.

Which is to say that you’re even more right than you’re claiming you are. We see the trailers we see because those trailers were literally conceived of before the script was written. The script was written to supply the marketers with the scenes required to create the trailers they originally envisioned.

That doesn’t mean clever writers like Shane Black and Joss Whedon can’t still write snappy dialogue for their superheroes. But it does mean that it’s the marketers who decide what stories get to be told in the first place.

It is a very weird world.

But, since we’re now going to see Pacific Rim on Monday, I suppose we’ll find out how accurate the marketing is for it soon enough. Stay tuned gentle readers for at least one Pacific Rim post early next week…

I’ve stopped watching trailer in the past couple of years for films I’m actually looking forward to they just give too much of the story away these days.

I went to see World War Z on Saturday night and before it they had a 3min+ long trailer for The World’s End that literally shows the entire narrative of the film from beginning to end and gives away a number of jokes and the final exploding building shot. So as a result I’m not sure I want to go see it anymore, I feel like I’ve already watched it.

They showed the Elysium trailer too but I just looked at my feet the whole time during that.

The only trailer that I’ve seen recently that is an actual ‘teaser’ is the one for Gravity which is short and tight and full of tension.

yep. i hear you. for me it goes back to the post i wrote almost exactly a year ago about spoilers. in brief: you can’t spoil a good film.

http://www.standbyformindcontrol.com/the-grey-ghost/