It pains me to admit it, but I enjoy watching reality television. The Bachelor has long been a source of fascination for me, and when I have an extra hour to kill in the presence of basic cable I am not above flipping back and forth between MTV’s Teen Mom and whatever happens to be showing on Bravo. Yes, these shows are exploitative, and that’s precisely the point for a “serious” filmmaker like myself: observing the contortions they will go through to dress up their cheap melodrama in the therapeutic language of self help (or the fantasy of an innocent quest for true love, or the promise that someone deserving will end up with a job) is part of the pleasure of the show. I can see the insincerity of intention, and I get to feel superior. I see through the façade, and marvel in a sort of queasy, disgusted fascination.

Yet when I head to the cinema to see a feature-length documentary, I expect some sort of firewall from the crass commercial motivations that dominate on the small screen. If I pay an admission fee, I have in theory entered the realm of the Artistic and the Serious. I have decided to give 90 minutes of my time to the director of this work, who is in turn unshackled from the need to endlessly entice me into coming back after the next commercial break with fresh promises of intrigue and humiliation.

Yet when I head to the cinema to see a feature-length documentary, I expect some sort of firewall from the crass commercial motivations that dominate on the small screen. If I pay an admission fee, I have in theory entered the realm of the Artistic and the Serious. I have decided to give 90 minutes of my time to the director of this work, who is in turn unshackled from the need to endlessly entice me into coming back after the next commercial break with fresh promises of intrigue and humiliation.

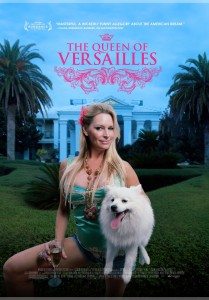

So it was that while watching The Queen of Versailles a few months back that I had the uncomfortable sensation of worlds colliding. The film had all the trappings of the Serious Documentary, from approving nods in The New Yorker and The New York Times to its placement among the International Documentary Association’s top five films of the year, yet in myriad tiny ways Reality was gnawing at the edges. From the perfunctory wallpapering of the scenes with music to the breezy, shorthand style of the editing to the conveniently non-committal relationship between author and subject, the firewall was coming down.

The modern verité documentary traces its roots back to the pioneers of the form in the 1960s. Whether using that phrase verité or rejecting it, trailblazers like the Maysles Brothers, Jean Rouch, and Robert Drew all had a great deal of hubris as they claimed to have found a sort of holy grail of truth. As their fellow traveler Ricky Leacock put it, “[what we’re doing] is totally different because this really has to do with reality.” Why? Well, for the first time the camera and sound equipment was small enough to be truly mobile, and they could get into social situations that were previously off limits. Also, they created rules for themselves. Narration was passé, as it told the audience exactly how to feel rather than letting them make up their own minds. Ditto with the use of music. They often even refused to conduct interviews, feeling it revealed too much of the author’s bias because it set up an artificial situation that would not have occurred had they not been asking the questions. If they did do interviews, they would often be shown with the interviewer and the sound equipment in the shot as a nod towards transparency. The idea of verité seemed simple: the subjects would be themselves, and the filmmakers would bring that reality to their audience.

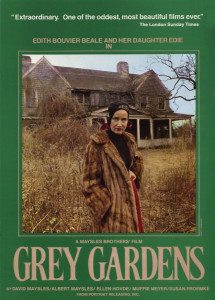

The issue of exploitation came up almost immediately, however, with the Maysles’ now-classic Grey Gardens a great case in point. This was a portrait of two society women—a mother and daughter—who now lived in squalor in their East Hampton mansion. It showed raccoons roaming the house, trash piling up in the bedrooms, and Little Edie (the daughter) flirting with the filmmakers wearing a bedspread as a skirt. Some critics scowled at the fact that the Maysles had shown the “aging flesh” of their fallen Hamptonites in such a raw form. Yet the Maysles could claim with some credibility that they were in fact respecting their subjects by showing them as they actually lived rather than in a prettied up form that would have been more acceptable to the town that they openly despised for its refusal to accept them. The women’s open embrace of the film when it came out was a convincing endorsement of its methods.

The issue of exploitation came up almost immediately, however, with the Maysles’ now-classic Grey Gardens a great case in point. This was a portrait of two society women—a mother and daughter—who now lived in squalor in their East Hampton mansion. It showed raccoons roaming the house, trash piling up in the bedrooms, and Little Edie (the daughter) flirting with the filmmakers wearing a bedspread as a skirt. Some critics scowled at the fact that the Maysles had shown the “aging flesh” of their fallen Hamptonites in such a raw form. Yet the Maysles could claim with some credibility that they were in fact respecting their subjects by showing them as they actually lived rather than in a prettied up form that would have been more acceptable to the town that they openly despised for its refusal to accept them. The women’s open embrace of the film when it came out was a convincing endorsement of its methods.

Critics also questioned the premise that these films were any less constructed or manipulative than the documentaries that came before them. Frederick Wiseman, who called his documentaries “reality fictions,” quickly derided the term cinema verité as a “pompous, overly worked, bullshit phrase.” Yet many of the early pioneers of verité really did believe in the fiction that they were getting closer to Truth, and by doing so they gave the form a generosity of spirit that looks almost quaint today. They really did want to speculate on the mysteries of human nature and to linger on the subtleties of character. They were idealists and humanists at heart.

Reality television has no such high ideals, of course, and one way of producing drama rather than waiting for it to happen is to keep the knowledge of the authors and that of the subjects in a constant state of imbalance. On a moment’s notice the bachelorettes may find that one of their number will be leaving town that very evening if they do not get a rose; the chefs on Top Chef will suddenly find ingredients added and kitchen tools missing; and the competitors on The Amazing Race will find that the pit stop they have been desperately longing for isn’t really a pit stop at all, and that they must keep right on going. This imbalance is a defining characteristic of competition reality shows (and, one might argue, of the whole genre.)

Which finally brings me back to Queen of Versailles. The film follows the travails of a timeshare property tycoon named David Siegel and his wife Jaqueline, who are endeavoring to build the largest house in America. How does the film treat its subjects? Are these people complex humans with idiosyncratic goals, dreams and desires, or experimental subjects on show for our amusement?

The opening sequences reveals a lot. The couple is shown on a huge throne of a chair, basking in the attention of the camera and clearly enjoying their wealth. Then comes the click of a DSLR camera, and the reveal that they are posing for a photo shoot.

But this is not just any photo shoot. It’s a shoot for the PR campaign of the very film we’re watching. And listen to the music: it has the lilt and dreaminess of a fairy tale, as if we’re hearing the soundtrack to the fantasy that they are living in. The film takes every opportunity to indulge the egos of its subjects, and as their finances sour with the onset of the Great Recession it gives them plenty of rope on which to hang themselves as spoiled, unsophisticated rubes. The pleasure here is the same pleasure I get from reality shows, albeit in a more sophisticated form. I see the filmmaker setting the subject up for a fall, and I get to enjoy the drama intended by the director as well as the disconnect between her stated goal (an honest portrait) and the actual result (a well observed documentary that is also a takedown of an easy target). And while there’s no contest to win, the unequal power relationships of the reality show are still in full effect.

Now, I will readily admit that there are problems with the argument I’ve just set up here. Queen of Versailles never claimed to be a work of cinema verité. One could argue that the photo shoot at the beginning of the film, by showing off the making of the documentary as just another piece of artifice, is offering just the kind of transparency that the verité pioneers would have approved of. And even the most scrupulous documentary filmmaker has a point of view on their subjects that may not be fully revealed until the film is complete. But even though The Queen of Versailles actually has a lot of very insightful things to say about how we think about wealth in America, I think the point still holds: we should be very aware of what kinds of pleasures this particular documentary is offering us.

The movie ends in an interesting way. David Siegel is put back in the throne chair for one final interview, only now he is chastened and beaten down. He reveals that things with his wife are not so good, and it is clear that he has told us secrets that he has not revealed even to her. As the anonymous hand of a makeup artist enters the frame to pat his face down and pretty him up for a few final questions, he asks wearily, “are we getting near the end?” The placement of the clip is brilliant, as it signals not only the end of the interview but also the beginning of the end of the movie, and the end of his humiliation as a subject of the film. We have had our fun with him, and now it’s on to the next thing.

It’s hard to make the argument that the Serious Documentary is in any kind of trouble. It is perhaps more alive than ever, as filmmakers from all around the world struggle to tell emotionally honest, politically astute, sociologically insightful stories. Yet it is interesting how effortlessly the notions of Reality TV have infiltrated so-called “serious” documentary. With its assumptions that you must titillate your audience to keep them in their seats, that you must judge your subjects in order to understand them, and that you must exploit to reveal, Reality TV is everywhere.

Og usually goes by the name Jacob Bricca. He teaches filmmaking at the University of Arizona and also directs and edits documentaries. You have seen his work if you’ve watched Lost in La Mancha or stumbled upon his ode to action movie clichés, Pure. His latest film Tatanka will be released soon.