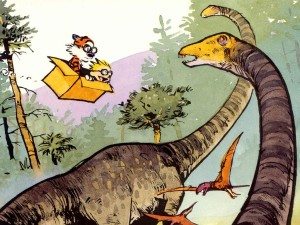

Thinking outside the box isn’t that hard to do.

You just scratch a small hole in the box, poke your thinking appendage through, and think away. No big deal. I don’t know why business types are always going on about it.

Living outside the box, however—that’s much more difficult. Even if you make it outside the box to begin with (no small achievement) surviving out there is plain dangerous. It’s a wild, untamed world with no walls. That’s why they call it outside of the box.

Living outside the box, however—that’s much more difficult. Even if you make it outside the box to begin with (no small achievement) surviving out there is plain dangerous. It’s a wild, untamed world with no walls. That’s why they call it outside of the box.

And, as if that wasn’t frightening enough, the box will miss you.

The box doesn’t like escapees. No siree. It hungers to swallow you back up in one slobbery gulp.

‘Get back in my box belly,’ it says. Sometimes it says that with its steel bar teeth. Sometimes it uses its rough, white pillowcase gums to express its discontent. Sometimes you don’t even hear the box coming; just slurp! You’re back inside and cramped and uncomfortable and not even allowed out for picnics.

So. Let’s go on a magical journey outside the box, right? What could go wrong? Are you with me?

In case you need some convincing, today’s Mind Control Double Feature collects two inspiring tales of men who manage, for a time, to escape the box. And then they live happily ever after…

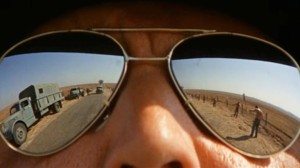

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

Them clothes got laundry numbers on them. You remember your number and always wear the ones that has your number. Any man forgets his number spends a night in the box. These here spoons you keep with you. Any man loses his spoon spends a night in the box. There’s no playing grab-ass or fighting in the building. You got a grudge against another man, you fight him Saturday afternoon. Any man playing grab-ass or fighting in the building spends a night in the box. First bell’s at five minutes of eight when you will get in your bunk. Last bell is at eight. Any man not in his bunk at eight spends the night in the box. There is no smoking in the prone position in bed. To smoke you must have both legs over the side of your bunk. Any man caught smoking in the prone position in bed spends a night in the box. You get two sheets. Every Saturday, you put the clean sheet on the top, the top sheet on the bottom, and the bottom sheet you turn in to the laundry boy. Any man turns in the wrong sheet spends a night in the box. No one’ll sit in the bunks with dirty pants on. Any man with dirty pants on sitting on the bunks spends a night in the box. Any man don’t bring back his empty pop bottle spends a night in the box. Any man loud talking spends a night in the box. You got questions, you come to me. I’m Carr, the floor walker. I’m responsible for order in here.

And what happens if you don’t keep order when you’re serving time on a Florida chain gang? That’s right. You spend a night in the box.

Spending a night in the box is exactly as pleasant as it sounds. Not spending a night in the box is better, but still not nearly as good as being free of prison altogether. That’s how Luke sees it in Cool Hand Luke.

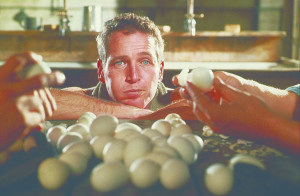

From the first shots of this film, you are perfectly placed to understand its central figure, Lucas Jackson (Paul Newman). While people go on and on about films with great endings, Cool Hand Luke trumps them all with a brilliant beginning. It is a film about character, and the opening scene lays this character out. You see him. You know him. You understand and empathize.

‘Violation,’ it says, right off the bat. You can’t do this and you can’t do that. Disregard the law, no matter how arbitrary, and face the wrath of the Man. But Luke doesn’t care. He’s the kind of fellow who drinks a mess of beer and cuts the heads off of parking meters, one at a time all the way down the block.

Why is Luke beheading these petty tyrants? He doesn’t even really know; can’t say when he’s asked. They just irk him, those dumb metal mouths, telling him—a human being—to move on or pay up. Who do they think they are?

There’s no complicated backstory about how Luke was unfairly fined for idling in a handicapped zone. Right here is all you need in order to know the fellow. It’s almost everything you can know about a man. Within the first two minutes of Cool Hand Luke, this character has bared his heart and soul for you to see.

From here, the film gets better.

Yes, Luke gets himself sentenced to a chain gang run under a brutal set of rules—and the rules are enforced by everyone too slow-witted to get their heads out of the box. That makes everyone a boss, starting with the warden, played by Strother Martin, his officers, and even the other prisoners who scrabble for position in their pathetic pecking order.

When Luke first smirks into the bunkhouse, the top con is Dragline—a loud-mouth goon portrayed by George Kennedy. Dragline thinks he’s a big swinging dick, but some things can’t be measured in inches. Not when you’ve got your sights set outside of the box altogether. Rule the roost if you want, Dragline, Luke’s going to fly. He has to. Your authority means nothing to man like him.

Beyond Dragline, this film sprawls a ton of other familiar and talented faces across the bunkhouse beds. (Harry) Dean Stanton is Tramp, Anthony Zerbe is Dog Boy, Joe Don Baker is Fixer. And yeah, that’s Denis Hopper as Babalugats.

I have no idea where the name Babalugats comes from, but it’s perfect. Please start naming your children Babalugats now. Thank you.

Luke’s arrival turns the world on its head. He just won’t stay down, even when he clearly can’t win. Luke sees what you want him to do, he sees what’s possible and rational, and does what he wants anyway. Why? He can’t put a name on it—that’s your bag. Rules just irk him. So Cool Hand Luke is the story of a man who bucks the system no matter how hard the system bucks back.

He’s all bluff and swagger but that’s like saying Martin Luther King Jr. was all talk. In Cool Hand Luke, bluff and swagger is holy.

Naturally the film has religious undertones. It isn’t hard to spot the visual cues that associate Luke with Jesus. They aren’t exactly subtle. On one level, they work; leading you to consider how domination and subservience are antithetical to what Christian texts dictate. On another level, it’s too much frosting. Respecting Luke because he’s compared to Jesus is overkill. It’s enough to respect Luke because he respects himself.

As Luke struggles to escape the cage of the world, he gets more and more tangled within it. These men he works with, these bosses who try to control him, his ailing mother (Jo Van Fleet; excellent)—they all get their hooks into him. That’s the way of the world.

And what does Luke have to help him get free? A cool hand of nothing.

I connect with this film at so many points and on so many levels, I’m never sure whether to laugh or cry when watching it. It feels like the filmmakers have poked a finger through the fabric of the universe so that you can watch the substance of your life roil out into the vacuum outside. Cool Hand Luke is beautiful, and cruel, and—without getting blue—some of the sexiest stuff you’ll ever see. If you’ve never seen Joy Harmon’s turn as ‘Lucille’ well, hold on to your hat. You may decide being controlled isn’t so unpleasant after all.

But it is. Like most of the world, Lucille’s just steering you around like a bumper car so she can laugh when your brains get jangly. Only thing you can do is fight your way free, even if it kills you, and it probably will.

Cool Hand Luke started as a book written by Donn Pearce, a man who’d spent time as a prisoner on a chain gang. Stuart Rosenberg, then a television director, wrangled the film together based on his book. It was his first feature. The late, great Frank Pierson helped Pearce write the script. The result isn’t any old prison film. It’s a challenge to authority. It’s a dare.

Cool Hand Luke was nominated for a mess of awards, and Kennedy won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. Rosenberg never made another film quite this good, but I’m not complaining. One like this is plenty.

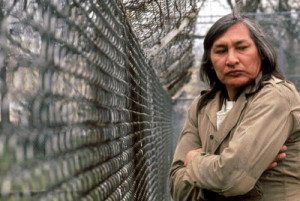

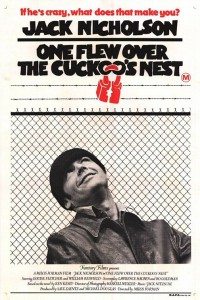

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

Everybody—and I mean everybody—should watch One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I recently read the novel, written by original acid head and Merry Prankster Ken Kesey, and that’s also a tight hand around your windpipe. Just like Cool Hand Luke, this tale relates the story of a man who can’t be chained.

Everybody—and I mean everybody—should watch One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I recently read the novel, written by original acid head and Merry Prankster Ken Kesey, and that’s also a tight hand around your windpipe. Just like Cool Hand Luke, this tale relates the story of a man who can’t be chained.

The film of Cuckoo’s Nest, as directed by Miloš Forman, serves up Jack Nicholson as Randle P. McMurphy. McMurphy—or just Mac—is a roustabout who just doesn’t much care about staying in line. With his fists and his wit and his wild laughter, he does as he pleases. If the Man wants to toss him in the clink for that, well let him try. As the film starts, McMurphy has conned his way from a stint on a work farm into an Oregon mental institution, where he thinks serving time will be sweeter.

He might have been right, too, if not for Mildred Ratched (Louise Fletcher), the head nurse on the ward. She’s a real ball-buster, who uses humiliation, intimidation, medication, and electroshock to dominate her charges. This is called therapy. Nurse Ratched says she just wants to teach her patients to be healthy members of society, and is that so terrible?

Yeah, lady. It is. Especially for Chief Bromden (Will Sampson)—the towering, mute son of an American Indian chief. Everyone just calls him Chief Broom and shoves him in a corner to sweep up. In the book, Bromden is the narrator, and we hear of his debilitating fear of what he calls “The Combine”—the vast conspiracy of machinery that makes up the box of the world. In the film, you’ll have to suss that stuff out for yourself, sorry.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest witnesses the battle of wills that is McMurphy versus Ratched. Wild freedom versus dominating control. In between and on the sidelines are the other patients. Again, like with Cool Hand Luke, these characters represent a wealth of acting talent. We’ve got Brad Dourif as stuttering, shy Billy Bibbit; Christopher Lloyd as the blustery Max; Danny DeVito loses the plot as the delusional Martini; Sydney Lassick squirms and erupts as the infantile Charlie Cheswick; Vincent Schiavelli looms as the epileptic Frederickson; and William Redfield plays the head bull-goose loony Dale Harding, an educated, sexually repressed mouse.

Mac shows up on the ward and pushes every button he can. Nurse Ratched has locked this corner of the universe down tight for decades and having a screw like McMurphy loose threatens the whole Combine with collapse. To start, he bets the other boys that he can put a bug up her ass. From there, his irrepressible antics inspire and overtake the ward as he bulls his way towards full freedom.

Alas, the box is hungry for him. It just isn’t so easy to slip outside its skin—and Nurse Ratched is a crafty, vicious pile of rat shit.

This is another film that will have you wondering whether to laugh, or cry, or beat your head against the walls in your need to feel free. Maybe you should try them all? You may say that no one can lift a marble hydrotherapy console—like the one Mac bets he can at the film’s beginning—but if we don’t do the impossible, how can we achieve the impossible?

The box wants us all wrapped up inside. Even if we see no way out, we’ve got to at least try, dammit.

In the history of the Academy Awards, only three films have swept all five major categories—best film, director, screenplay, actor, and actress. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is one of them. (The others are It Happened One Night (1931) and Silence of the Lambs (1991)). What does that tell us? Well, for one thing, it means we’re not the only ones who dream of thinking and living and howling outside the box.

Maybe if we all push on the walls together?