And in the beginning god created light. Shortly thereafter we got monsters.

Always with the monsters.

Monsters are an essential part of creation. Basically, you can’t have a real creation shindig without ending up with a couple of horrific creatures bent on destruction: a dastardly snake, a three-eyed ball of electric spikes, a half mermaid/half Sasquatch thing with vile antisocial tendencies. You know, monsters. They’re everywhere. There’s probably one behind you right now.

As it turns out, you’re particularly likely to get monsters when the creator in question is not an all-powerful ür being like god or Keith David, but rather a none-too-humble human, or a gaggle of humans.

Luckily, accidental monster creation makes for compelling cinema. Nothing is quite so charming as watching someone try to create something beautiful but ending up with a ravenous pile of hyper-acidic sludge instead.

In other good news, when it comes to understanding the emotions and motivations of egomaniacal god pretenders, we’d be hard pressed to find people better suited than film directors. This isn’t coincidence; making movies is creation, and all-too frequently it is creation corrupted by diabolical hands — studio nabobs, incompetent screenwriters, Lindsay Lohan, etc. Film directors know what it is to have a vision of beauty, to pour one’s energy into bringing that dream to life, and to end up with Dune for their efforts.

This week’s Mind Control Double Feature digs into corrupted creation with two horror films that even non-horror fans should enjoy. No piles of steaming innards on display here. No oogity-boogity gonna getcha shocks. You’ll only experience the terror of your creative efforts gone abominably astray.

You know. Like normal.

For today, “It’s alive” is the worst news possible.

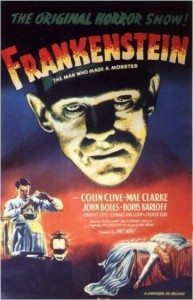

Frankenstein (1931)

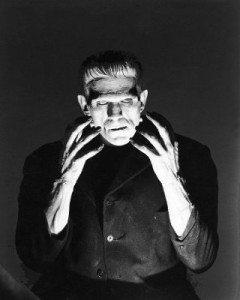

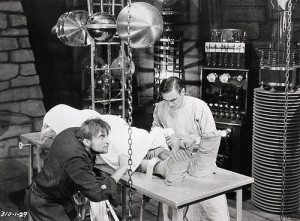

James Whale’s 1931 version of Mary Shelley’s gothic horror tale Frankenstein wasn’t the first or the last. It is, however, the classic. It is the one that features Boris Karloff as the monster (never named, and certainly never named ‘Frankenstein’). It is the one that features Kenneth Strickfaden’s mesmerizing electrical effects — which have been part of every decent Frankenstein production since. It is the one that, via makeup artist James Pierce, envisioned the monster with his now-iconic flat head and creepy neck bolts.

James Whale’s 1931 version of Mary Shelley’s gothic horror tale Frankenstein wasn’t the first or the last. It is, however, the classic. It is the one that features Boris Karloff as the monster (never named, and certainly never named ‘Frankenstein’). It is the one that features Kenneth Strickfaden’s mesmerizing electrical effects — which have been part of every decent Frankenstein production since. It is the one that, via makeup artist James Pierce, envisioned the monster with his now-iconic flat head and creepy neck bolts.

It is Frankenstein. And when people ask if you’ve seen Frankenstein, they mean this one.

Whale’s Frankenstein is also the version that gave cinema one of its repeating motifs, a line of dialogue that reverberates throughout film today, even eighty years later:

It’s alive!

Certainly you know something of the story of Frankenstein, but lest you be confused by horrible Kenneth Branagh boondoggles or excellent Mel Brooks riffs, here’s what the classic version covers:

There is a gifted but imprudent scientist by the name of Heinrich Frankenstein (Colin Clive). He has become estranged from the medical establishment due to his insistence on pursuing blasphemous studies on the creation of life. Locked away in a tower laboratory, he avoids his fiancée (Mae Clarke) in order to concentrate on elevating a patchwork man (Boris Karloff) — sewn together from stolen corpses — into animation and consciousness. He is assisted by a hunchback named… Fritz. Yes. Fritz (Dwight Frye). Not Igor, or Ygor. (Ygor did not appear until The Son of Frankenstein, the third film in this series of Frankenstein pictures, then portrayed by Bela Lugosi).

Boris Karloff is no Bela Lugosi, but he can do jazz hands

As you might have guessed from my introduction to today’s double feature, Heinrich succeeds in creating life but it does not go exactly as he planned. It turns out creating life is sort of difficult to get right. Ask your mom about that.

But what does one do with offspring when it proves monstrous? Does your initial joy at bringing life into the world allow you to overlook its terrifying countenance? Or do you cast it from you in horrified disgust? Again, ask your mom about that.

In Frankenstein, the Doctor sees — correctly or not — the threat his monstrous offspring presents and tries to kill it. He gets points for effort but loses marks for execution. Cue the angry townspeople wielding pitchforks and torches.

As a film, I must admit that I find Frankenstein pretty corny. It was a serious shocker at the time it was released and heavily censored for violence, blasphemy, and other horrors. Today, it’s kind of cute and only frightening if you’ve never seen anything scarier than Viagra commercials.

Still: it is Frankenstein and if you give a whit about film, you should see it. It is the spring from whence we emerged. It gave us life, and like the mutant, despised, monstrous children we are, we ought to show fealty.

Watch Frankenstein. Think about the gothic ideas that underpin its timeless tale. Wonder at how you’d feel to see your dream come to life and then threaten to destroy all you hold dear.

It’s alive, indeed.

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Roman Polanski’s first American film, Rosemary’s Baby, is a horror movie everyone needs to see — even if the idea of horror movies makes you want to turn on every light in the state. The only thing that’s scary about it is how breathtakingly good it is.

Roman Polanski’s first American film, Rosemary’s Baby, is a horror movie everyone needs to see — even if the idea of horror movies makes you want to turn on every light in the state. The only thing that’s scary about it is how breathtakingly good it is.

Okay. That’s not really true. Rosemary’s Baby is exceptionally creepy. Like finding out your new energy drink is made out of the tears of children creepy.

Polanski was, at the time, one of the hot European directors that Americans wanted to co-opt in order to make themselves wealthier than god. Robert Evans — head of Paramount — got the unreleased book by Ira Levin from schlock director William Castle and recognized its potential. He let Castle produce but used the material to ensnare Polanski.

While Rosemary’s Baby is a simple tale of cursed motherhood, it is that tale told perfectly. Since its release there have been countless demon-child films and none even remotely compare to Roman Polanski’s manipulatively brilliant picture. Rosemary’s Baby comes from the heart. It is a tale of creation gone astray and it was a film that ended up having profound personal resonance for its director.

Before you read on about this film, though, you ought to know that whatever Polanski intended when he wrote the script (for which he was nominated for an Academy Award) and whatever he thought when he shot the film, it was only a year after this film was released that his wife, Sharon Tate, was murdered by the Manson Family in their home. Sharon was eight and a half months pregnant with Polanski’s son.

And so we might presume to assume that the director’s feelings about the creation of life, and about the acceptance of one’s creation’s imperfections have changed. Speculate as you will.

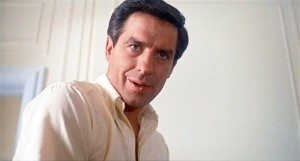

But Rosemary’s Baby. I just watched this film yet again and loved it even more than ever. In the picture, Mia Farrow plays Rosemary Woodhouse, wife to aspiring actor Guy (John Cassavettes). They rent an apartment in a New York building with an occult history. There, the occupants — all played by old Hollywood actors such as Elisha Cook Jr. (the gunsel Wilmer* in Maltese Falcon) — make a secret deal with Guy: let the devil impregnate your wife and we will give you what you desire.

It is a story of souls sold. And it’s no coincidence that those doing the buying represent the film industry — Ralph Bellamy plays the highly respected and totally demonic Dr. Saperstein — or that Guy is an aspiring actor looking for his big break. The characters even discuss the “theater of religion” before poor Rosemary is drugged and raped by Satan in an excellently bizarre dream sequence.

Polanski pulls out all the stops here building a mood of helpless doom. We watch Rosemary’s innocence peel away through a camera that’s set too low and too close and moves too late or too early, always keeping us a step off-balance. Polanski frames scenes in Rosemary’s Baby in a way that cuts off heads, or leaves the character who is speaking just out of your view.

Rosemary is thrilled to be creating something, but from every direction her efforts are corrupted by meddlers with evil intentions. Even her loving husband, who claims to have her interests at heart, betrays her. He leaves her to suffer, to endure pain, and to waste away for his own gain.

The ending is one of cinema’s greatest. In case you haven’t seen the film yet, I’ll keep mum, but I want you to consider as you watch: if you put your soul into creating something, into protecting it from all harm, what would you do when you discovered its corruption?

Fascinating anecdotes surround the production of Rosemary’s Baby. It was during the filming of the kitchen party scene that Frank Sinatra publicly served Mia Farrow with divorce papers — he had insisted she give up her acting career. Mia broke down sobbing then continued the shoot, convinced the role was worth it. For the scene in which Farrow walks into Manhattan traffic while heavily pregnant, Polanski was forced to operate the camera himself. Why? It was real New York traffic and no one else would risk it. When Rosemary calls Donald Baumgart — an actor whose personal tragedy has allowed Guy to succeed — the voice on the other end of the line is Tony Curtis’. Farrow didn’t know in advance and her half-recognition of his famous voice added an excellent soupçon of confusion to the scene.

And I have not even mentioned Ruth Gordon who plays neighbor Minnie Castevet. Gordon you will recognize as the eponymous lead from Harold & Maude. It is her skill that adds the ideal sheen of humor to the horror here. Minnie talks twice as fast as everyone else, never lets anyone finish a thought, and insinuates herself in Rosemary’s life like a virulent strain of fungus.

There is much to love in Rosemary’s Baby. There is even more to consider hidden down its long hallways and within its dark closets. Mia Farrow is a pale beacon of talent and if you don’t empathize with her and her plight, it’s time for you to get more creative.

Bring something to life and see how it turns out.

* In a cool coincidence, Dwight Frye who plays Fritz in Frankenstein also portrayed Wilmer in the earlier, significantly less famous 1931 version of The Maltese Falcon.

Thanks for pointing me to this slice of cinematic delight! If I ever had a deep conflict between which character plaid by one and the same actor/actress I would like more, it has been Ruth Gordon’s deliverance of Maude and of that neighbour in Rosemary’s Baby. Two so very different films and yet both have been milestones in cinema history and sheer pleasure to watch. Would you also happen to have a Double Feature on dubious mother figures?I If not I would love to see Harold’s mother playing versus … hm, whom would you suggest?

Have you seen the Korean film Mother? It’s pretty awesome.

Unfortunately I haven’t so far but I know about its impressive award count and the overall premises of the film. I will do my best to lay my hands on it. Thanks a lot for the recommendation.