You can never step in the same river twice, it is said, for though they remain in the same place, they are ever in motion. We curious humans have long struggled upstream to find their sources and drifted downcurrent to float from their mouths. They lie on beds and are protected by banks. Some are thick with crocodiles, others swarm with microscopic critters looking to set up shop within you. Some are cool and clear and inviting, others full of rapids and waterfalls.

But most of all, rivers exist as metaphors. It’s really their best and most useful quality. To travel a river is to travel inside yourself. To find a river’s source is to find the beginnings of humanity itself. To travel to a river’s mouth is to see humanity’s end. The rivers we travel in films and literature are the ones that flow inside of us.

Also, they’re fun to swim in.

But we’re not here today, with this week’s Mind Control Double Feature, to frolic amidst the rapids of a cool mountain stream. Rather, we are here to lose our minds deep within the jungle, to travel to the mouth of one river and the source of another. Nothing’s more primal than a river in a jungle. Jungles are ancient and thick with life. We came from the jungle. To return to it is to return to our collective past. We’re taking the river deep inside ourselves today, and we’re going to go mad doing it.

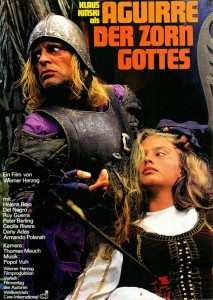

Aguirre, Der Zorn Gottes (Aguirre, The Wrath of God) (1972)

Werner Herzog had made only two movies when, reading a history of a 1560 Spanish expedition down the Amazon River from Peru in search of El Dorado, the mythical lost city of gold, he was inspired to furiously write a screenplay in a matter of days which, although using actual historical figures such as Lope de Aguirre, is for the most part fiction. Writing it he wasn’t thinking of who would play Aguirre. “But,” says Herzog, “the moment I finished it I knew it was for Kinski and sent it to him immediately. Two nights later, at 3 a.m., I was awakened by the phone. At first I could not figure out what was going on. All I heard were inarticulate screams at the other end of the line. It was Kinski. After about half an hour I managed to filter out from his ranting that he was ecstatic about the screenpay and wanted to play Aguirre.”

Kinski is, to be sure, insane, and therefore the ideal actor to play the part. (For more on Kinski, watch Herzog’s documentary My Best Fiend). The story is a simple one. An expedition heads out, and calamity after calamity befalls it. Aguirre, not in charge at first, rises up against the leaders and takes over the expedition, promising untold riches. But things grow worse still. Indians attack. Many Spaniards are killed. The rest are starving. They hallucinate and begin to go mad. Aguirre names himself the very Wrath of God. At the end, there are monkeys.

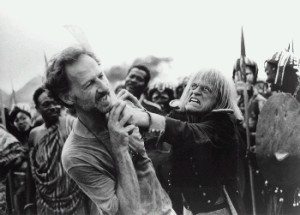

This is a movie about a journey into insanity, with Kinski as our guide. Herzog has endless stories to tell of Kinski’s real-life lunacy. “During filming he would insult me every single day for at least two hours.” During one of his daily tantrums, Kinski quit the production, began packing his things, ready to take a speedboat back to civilization. Herzog relates what happened next:

I told him I had a rifle and that he would only make it as far as the next bend in the river before he had eight bullets in his head. The ninth would be for me. He instinctively knew that this was not a joke any more and screamed for the police like a madman. The next police station was at least 300 miles away though. I would not allow him to walk off the film. He knew that I was serious, and for the remaining ten days of the shoot he was very docile and well behaved… Sure, the man was a complete pestilence and a nightmare to work with, but who cares? What is important are the films we made together.

It should be noted that in his own way, Herzog is at least as mad as Kinski, but his madness has direction, and that direction is filmmaking. Aguirre was not shot on a set, it was shot in the South American jungle. The budget was a few hundred thousand dollars. Most of what was shot was used in the finished movie. Herzog looks at movie-making as a great struggle that should by no means be easy or fake. In the movie, Aguirre takes on nature itself, and goes mad in the process. Herzog, to make the movie (and others, most notably Fitzcarraldo), likewise takes on nature, knowing no other way to capture the kind of deeper truths he is after.

The jungle in Aguirre is real, and you feel it. The opening shot of a high ridge among the clouds and the train of indigenous peoples walking along its crest is gorgeous and haunting, a sign of things to come. Aguirre was only Herzog’s third movie, and in terms of his fiction films, I think it’s his best.

The score to Aguirre, by Popol Vuh, also stands out, with its ethereal, synthesized voices, as if the jungle was alive and singing,

Aguirre travels down the Amazon into insanity. What happens if we travel backwards, upriver to the source? What madness awaits us there?

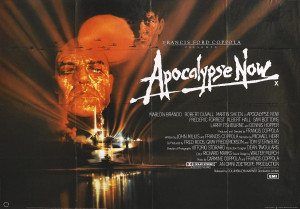

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Apocalypse Now is one long hallucination. It’s set during the Vietnam War, but it’s not about the war, and endeavors not at all to show the conflict as it “really was,” whatever that means. Instead it uses the setting to get at something much deeper and stranger. As Coppola said, it is the war. Decide for yourself what that means. He also said, when it premiered at Cannes in ’79, “We had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane.” (By all means check out the fantastic documentary Hearts of Darkness for a follow-up to this double feature, which shows the madness surrounding the making of Apocalypse Now.)

There’s so much wild history surrounding the movie, it’s useless to go into it here. Suffice to say, is was a project years in the making, George Lucas was originally going to direct it (then made Star Wars instead), it took a year and a half in the Philippines just to shoot it, star Martin Sheen had a heart attack early on, Brando was too fat to play his role as written, and nobody, Coppola most of all, thought they’d get a watchable picture out of it.

Madness won out in the end. Apocalypse Now is one of the greats. Sure, you’ve seen it already, but in the same way a river may never be stepped in twice, neither may a great film ever be seen twice. Every time you watch it, you’re someone new, and the film means something different.

In this case it’s especially true, because you’ve just watched Aguirre, The Wrath of God, maybe for the first time, and as Coppola has acknowledged, Herzog’s river masterpiece was a huge influence visually on Apocalypse. The two movies flow into one another.

Coppola made his movie even more hallucinogenic than Herzog’s, with the river leading not only into humanity’s ancient past, but into its literary and religious past as well. It’s Virgil and Dante and Eliot and of course Conrad (on whose book Heart of Darkness the movie is vaguely based) thrown together in a misty enjungled heap.

It’s full of weirdly great perfomances, from Sheen’s blank slate to Dennis Hopper’s acid-head photojournalist spouting Eliot’s poetry to Robert Duvall’s napalm loving surfer to a very young Lawrence Fishburne to Brando’s half-lit, monstrous god.

I saw Apocolaypse a number of times as a teenager, and every time Brando’s speeches put me into a dreamlike state from which I’d awaken as the movie ended, never sure what had happened beyond a terrifying impression of something awful and profound that I’d have to see again to understand. The one piece of advice I always remembered: never get off the boat.

The sound design of Apocalypse was at the time something brand new. Walter Murch, sound designer and film editor extrordinaire, creates an entire jungle world purely out of sound. A stand-out scene takes place at the bridge beyond which no one travels. Willard (Sheen) looks for a commanding officer in the darkness as colorful explosions light up the sky. A soldier lines up a mortar to shoot a Viet Cong soldier across the river who won’t stop screaming. The sound mixes down until nothing but the screams are heard. The soldier fires. The screaming stops. The sound returns.

Kurtz’s upriver compound is shot like the entrance to hell, with boatloads of white-faced natives silently parting to allow Willard and his party inside, as though they were guests long expected. Is Kurtz (Brando) a god? The devil? A monster? The lizard brain of us all made manifest? Decide for yourself. Apocalypse Now provides no answers. It takes us on a journey and forces us to look within. Watch out for tigers.

It’s no easy task exploring the rivers within. Go too far and you’re liable never to come back the same, if at all. These two movies are masterpieces by very different master filmmakers. Just the sort of single-minded loons you want steering the boat, if you ask me. Who better to explore insanity than the insane? Have fun!

I have watched both, Aguirre the film and Herzog’s documentary about Kinski – My Best Fiend. The latter had me wondering and marvelling about the persona Herzog must be for actually being capable of not only working with Kinski, but for tickling the very best performances out of him. I clearly remember Herzog’s journey back in time in Kinski’s footsteps, one of the most amazing documentaries of human collaboration, acceptance and artistic interaction. Everyone claims Kinski was crazy, ego-maniacal, genial and I believe he was all of it, but I guess the one person who really could put all that to a film’s advantage was Herzog. The part I most clearly remember is when Herzog shows Kinski’s step-by-step transformation into Aguirre himself. Often it has been claimed that actors were kind of transforming into the character they were portraying, but seldom did it seem to ring more true than in case of Kinski-Aguirre. It was both very sad and extremely fascinating to follow Kinski and Herzog down that road …

That is indeed a fascinating documentary. Equally worth your time is the doc about the making of Fitzcarraldo, Burden of Dreams. And then if you really want to plunge deep into the mind of Herzog, read his book about that same movie, Conquest of The Useless. I’ve lately heard that Kinski’s autobiography is itself an insane performance piece. Going to read that one sooner or later…

I wholly agree, have watched the making of Fitzcarraldo and do own in fact everything Herzog has ever done in collaboration with Kinski (and many of those without). I never tire of re-watching those for it is some of the most intense chapters of film-making I have seen. There is a wonderful thick volume in German about Klaus Kinski which claims, that it only offers 5 film images, no real biography but lots of tids and bits and that one might discover Klaus Kinski inside.