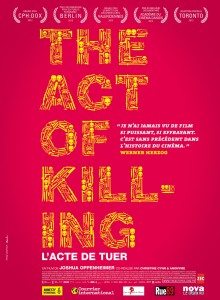

Killing is not a difficult act to accomplish. There are countless ways to get the job done. Be they bloody or tidy, quick or prolonged, sadistic or unfeeling—most murders are a simple matter of exerting physical pressure against an impressionable medium. Living with the memory of murder is likewise not difficult, if Josh Oppenheimer’s documentary, The Act of Killing, is taken as a guide.

This film, which I somewhat reluctantly motivated myself to see last evening, was not what I expected.

This film, which I somewhat reluctantly motivated myself to see last evening, was not what I expected.

I had thought the film would be horribly, traumatically dark. I expected to see men who, motivated by political forces, had killed hundreds of innocents. I thought these men would be confronted with the monstrosity of their actions via cinematic re-stagings so they could react with dramatic emotion.

All of that is in The Act of Killing, but it is not The Act of Killing.

The documentary introduces us to Anwar Congo, an elderly ‘gangster’. During the 1965 political upheaval in Indonesia, he was one of the men who helped rid the country of Communists—those being anybody whom the Suharto government wanted killed, including intellectuals, landless farmers, ethnic Chinese, and a few actual Communists. Millions of people were slaughtered.

Anwar was a jovial thug who personally murdered at least a thousand with the tacit support of the administration. He, along with his buddy Adi Zulkadry, conducted interrogations, tortured subjects, murdered them, and disposed of their bodies. This film—for most of its length—is their fond reminiscence of the heady days which made their famous names.

Anwar Congo is not a monster. He is a hero. That is how, together with his compatriots, he endeavors to tell the truth of those times. He does this through amateurish recreations and candid conversation. Much of this casual nostalgia about mass murder is commonplace, and that’s as evil as anything on display. These men worry about how admitting that they were the cruel ones—not the Communists—will affect the country. They do not concern themselves about the fact that they were cruel.

As the documentary progresses, we meet other men who took part in these atrocities. To varying degrees, they all express little shame or even awareness that what they did was wrong. They do not react with dramatic emotion to the fact of their murderous natures. There is no denial because there is nothing to deny.

On the contrary, their patriotic efforts helped spawn a multimillion-member paramilitary organization, Pemuda Pancasila. This celebrated group today continues to thrive on illegal activity and intimidation. It’s the sort of right-wing goon squad that the Vice President of Indonesia is happy to come support.

It is only as The Act of Killing unspools that Anwar begins to wonder about what he has done—and it is mostly only Anwar. Those moments, when they do clarify amid the nastiness and callousness, are essential. Everyone should see The Act of Killing. This is not because it is a great film, but because it has managed to capture something cryptic and primal. The intangible here comes fully into the light, like a ghost walking into Johns Hopkins for an MRI.

There have always been and likely always will be humans who deny others their humanity. The Act of Killing shows us what happens when this denial crumbles. Trying to imagine how this appears is not acceptable when the opportunity to witness it now exists.

The things that are discussed and re-enacted in the documentary are no worse than what fills the daily news. It is no more a masochistic wallow in misery than the New York Times. Only, in this documentary, horrors are discussed and re-enacted by the men who caused them to be. You will also see these men abraded by the locals who relent to take part in their historical dramas. These actors include their own children.

To say that these moments are powerful doesn’t cut it. You are witnessing truth, not in terms of facts and justice, but in terms of self-awareness.

There is one scene in which Anwar Congo’s convivial neighbor—who tags along—tells Anwar and his colleagues a story. It is the story of how his Chinese step-father was called out into the night and killed. He tells the story with a smile on his face, and apologizes if it sounds like he’s being accusatory. That is not his intent.

As a boy, I buried my father by the side of the road because of men like you. Shall we add that story to your truth-telling? Use it if it helps.

The Act of Killing is a maze for its subjects to run. They build it and follow it and we watch. There are many dead ends featuring disturbing, amusing, or dull tableaux. Much of the historical re-enactments fall in this category. Do not go to The Act of Killing expecting sinuous women dancing beside a giant fish and images like that to be substantial. They are visually pleasing asides that only contribute to tone.

Expect to see The Act of Killing and understand how people can live with their monstrous deeds. Expect to learn how cruelty can be celebrated. And expect to see what happens when one reaches the end of their maze.

There is a nameless minotaur waiting.

The Act of Killing is well worth seeing. These killers are considered heroes, including by the current vice president of Indonesia who praises them in the film. Impunity persists in Indonesia for these crimes and for later ones committed by Indonesia’s armed forces from the invasion and occupation of East Timor and to ongoing violations in West Papua. Human rights groups are supporting an appeal from survivors for the Indonesian government to acknowledge the truth about the 1965 crimes and to apologize and provide reparations to the victims and their families. See http://etan.org/action/saysorry.htm