Starring Marlon Brandon. Directed by Elia Kazan. A story of an aspiring hero overcoming his corrupted brother to lead his community to freedom from tyranny. I speak, of course, of Viva Zapata!*

You thought I was talking about On the Waterfront? No silly; that’s part of today’s Double Feature. It’s Kazan/Brando day here at SB4MC!

You thought I was talking about On the Waterfront? No silly; that’s part of today’s Double Feature. It’s Kazan/Brando day here at SB4MC!

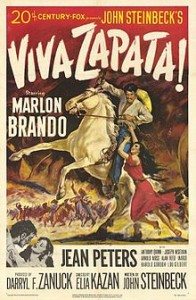

From a distance both films can be encapsulated in identical way but they aren’t that easy to mistake for one another. That’s to Viva Zapata!‘s chagrin as, despite its swoon-inducing poster, the film isn’t all that exciting.

Viva Zapata! came out in 1952, three years before On the Waterfront. It’s basically a hagiography of Mexican revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata (Brando), co-starring Anthony Quinn and Jean Peters. The script is by none other than John Steinbeck, author of Of Mice and Men, Cannery Row, and The Grapes of Wrath. Director Elia Kazan—later tainted by his willingness to testify before the House un-American Activities Committee—was one of that generation’s most impressive and respected filmmakers. It’s thanks to him that we know about Method Acting and recognize names like Brando, Beatty, Dean, and Wallach.

So why is this film so dull?

It’s not the costume design, which makes me wish bandoliers weren’t so aggressively militaristic and heavy. It’s not the cinematography, which has occasional bright moments. It’s pretty much everything else. Viva Zapata! just hasn’t aged well.

When it came out, Viva Zapata! was certainly well received. Quinn won an Oscar, and Brando and Steinbeck were both nominated. Watching it for the first time last night, though, I only made it through the first hour before I started compulsively looking at the clock every few minutes. ‘Dull, dull, impenetrably dull’ I thought as I endured for your sake. I watched the film’s characters pose for tableaux after tableaux in which they mouthed inspiring words—but I couldn’t picture an actual human being getting any of that dialogue out with a straight face. It was all just so very important, like the instructions before a standardized test. Then each scene would end abruptly, cutting to farther forward in this idolized man’s life.

I didn’t know much about Zapata before I watched Kazan’s film. I know little more now that I have. An illiterate peasant (actually, he grew up educated), Brando’s Zapata is the sort of man who flies into temper when his beloved townsfolk experience the abuse of the gentry. At the film’s start, when he first speaks for his village during an audience with President Porfirio Diaz, Marlon Brando’s dusted fury promises a visceral performance to come. It just fails to congeal.

This may be partially due to his ridiculous eyeliner, which granted does make him appear slightly Hispanic, and his fake mustache. More likely it’s due to the impenetrable divide between what happens on screen and what we recognize reality to be. You can’t get worked up over nothing, even if it’s amped up nothing.

To be clear: the Mexican Revolution—that’s not nothing. It’s this Reader’s Digest retelling of it that lacks humanity.

We watch Zapata struggle to win the woman he loves, even though we never glimpse why he loves her or how he expresses that love. We watch him reluctantly join the rebellion led by Francisco Madero, but if there are decisive battles or acts of derring-do, those mainly don’t make the cut. Instead it’s time for another speech in which normal people speak as if they’re running for office. Each scene is an archetype in which cypher characters voice the concerns or dreams of entire classes of people. Stagey, that’s what it is.

Wherever you can look – wherever there’s a fight, so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready, and when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build – I’ll be there, too.

That quote is from Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, and that’s how this dialogue sounds, too. After Tom Joad gives that speech in Wrath, however, his mother says she doesn’t understand. Then Tom admits he doesn’t really either and they go on being Okies living hard times in a hard world.

In Viva Zapata! there’s no time to cast a curious glance at the meaning in each speechlet, because the next message is coming and then another. If you don’t understand, or don’t agree, tough. Poor Emiliano. All he ever wanted in this textureless Romantic vision of the world was his symbolically pure white horse and freedom for his people.

Brando isn’t bad as Zapata, but I didn’t feel him beside me in the dark. His acting grabs you by the lapels in On the Waterfront and roughs you up in Streetcar Named Desire, but here he’s got nothing tangible with which to get under your skin. The character isn’t real even though Zapata actually existed.

Melodrama might work in fiction, but it’s a hard play for a historical recreation like this. David Lynch pulled it off in The Elephant Man, but Kazan spreads it way too thick for a man such as Zapata. He was a hero, but he was also just a man.

Anthony Quinn, who has less exposition to handle as Emiliano’s brother Eufemio, and Lou Gilbert as the tender-hearted Pablo both give solid performances that feel less warped by unpronounceable emotions. They want, they dream, they die. They are not a white horse nor a glimmer in the eye of today’s unyielding youth. They do not constantly pose as if for a sculptor.

Sorry Brando. This revolution fails to roil. Viva Zapata! dives headfirst into that familiar biopic trench; It conglomerates the highlights, makes up some simple symbolism, leaves the details to die, and drowns.

Viva Zapata!? Zapata está muerto.

*(Exclamation point not editorial.)

My favorite line from the film was, “Do you think three women and a goose make a market?”

I think that was the point at which we both gave up on the film. The difference between us of course being that you went on watching and I went to bed.

But that scene was the romantic heart of the film! And that goose was hottt.