There are two kind of men in Western films. There are those with ropes around their necks and those that do the shooting. Or maybe there are men in black hats and men in white hats? Or maybe the two kinds are good men, bad men, and ugly men? You just have to decide whether the good/bad/ugly men are substantially any different from each other, why anyone would call a brunet ‘Blondie’, and if any of this applies to women.

These are deep, philosophical questions which Westerns are perfectly suited to address.

The Western — as a genre — has gone squirrelly lately, though, focusing for some bizarre reason on the way things actually might have been in the American West in your great great grandpappy’s day. This is weird because, primarily, the Western has always been about mythical times populated with mythical people — kind of like biopics are today.

In Westerns, good and evil are clearly defined. Situations are grand, nature and progress take on antagonistic roles, and disagreements are settled during showdowns on dusty streets.

Yep. I love me a good Western and it’s high time we tossed a pair of ’em at you for a Mind Control Double Feature. Today we’ve got two classic tales of the old west that never was. These two films fit together like yin and yang, like black and white, like Taylor Swift and twerkin’. They — by design — reflect and comment on each other.

So draw up a chair and watch, you yella bellied snake, that is if you’re fast enough.

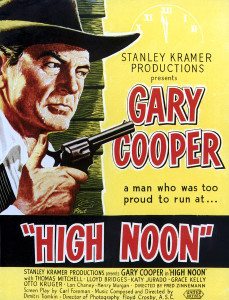

High Noon (1952)

When people talk about Westerns today, they generally include Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon on the list of classics. It’s not a classic Western, though. It is, in many ways, contrary. Westerns were usually about gunfights and sweeping scenery and heroes in ten-gallon hats. For most of its length, High Noon has none of that.

When people talk about Westerns today, they generally include Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon on the list of classics. It’s not a classic Western, though. It is, in many ways, contrary. Westerns were usually about gunfights and sweeping scenery and heroes in ten-gallon hats. For most of its length, High Noon has none of that.

It starts with Marshall Will Kane (Gary Cooper) retiring. He’s getting on in years and has just gotten married to Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly), a Quaker and a pacifist. Their plan is to leave town and begin a new life as shopkeepers. As they’re on their way out the door, however, word comes in that Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) has been released from prison on a technicality. Frank’s a nasty character that Kane sent up a few years back. He’s sworn to seek bloody revenge on the Marshall and he’s arriving on the noon train — that’s about an hour away.

In fact, that’s exactly an hour away, as everything in High Noon happens in real-time. One of its main characters is the clock, which slowly ticks down the minutes until Miller’s arrival.

In fact, that’s exactly an hour away, as everything in High Noon happens in real-time. One of its main characters is the clock, which slowly ticks down the minutes until Miller’s arrival.

So, unlike most Westerns, this one clearly is saving all the gunplay until the end. The relatively short running time (85 minutes) spends the rest of its length investigating the character of those who might stand between Miller and Kane, or beside Kane as he stands up against Miller and his gang.

High Noon tracks with Will Kane as he reclaims his badge and tries to convince the townsfolk he’s protected to join with him. Among these timid creatures we find young Lloyd Bridges as the ex-deputy, Harry Morgan as the best friend, and Katy Jurado as both Will and Frank’s ex-lover. Eagerly waiting at the station for Frank’s arrival there are also three members of Miller’s gang, including Lee Van Cleef.

I don’t want to give too much away, but nobody will help Will. Across the town, in church, in the parlors of his friends, in the halls of justice: everyone finds an excuse to leave the Marshall twisting in the wind. Run, they tell him, but Will Kane won’t.

I don’t want to give too much away, but nobody will help Will. Across the town, in church, in the parlors of his friends, in the halls of justice: everyone finds an excuse to leave the Marshall twisting in the wind. Run, they tell him, but Will Kane won’t.

Interestingly, this film was scripted Carl Foreman, a writer who — during production — found himself in the sights of the House Unamerican Activities Committee. Many have seen parallels between Gary Cooper’s character’s predicament and Foreman’s, as both men experienced abandonment by their friends and colleagues at their time of greatest need. Foreman ended up blacklisted by Hollywood and moved to England before High Noon could be released.

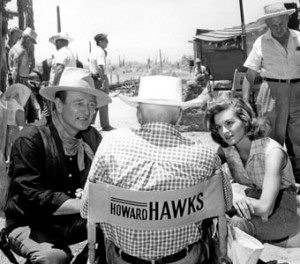

Other people — notably famed Western (and Comedy and Gangster) director Howard Hawks and John Wayne — hated High Noon. To them, it trampled everything that the genre stood for. American heroes wouldn’t need to crawl around town begging for help when faced with a few measly desperadoes, they said. They’d just man up and mow them down.

That didn’t stop Wayne from accepting Gary Cooper’s Best Actor Oscar on his behalf, however. Nor did Wayne and Cooper’s friendship keep Wayne from making a response to High Noon a few years later.

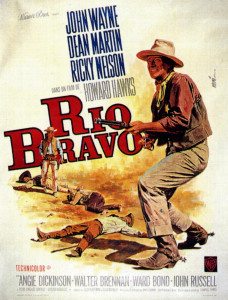

Rio Bravo (1959)

Yep. That’s right. Rio Bravo — Howard Hawks’ and John Wayne’s well-loved Western — is a direct response to High Noon. Where High Noon is a tense, terse, interpersonal close-up on how we (as Americans) face looming threat, Rio Bravo is an entertaining, expansive, rough-and-tumble Western that gives High Noon the finger. In a technically adroit ‘fuck you’ to Zinnemann and Foreman, Hawks avoided close up shots almost altogether in Rio Bravo. You want to zoom in on the failures of American heroism? Not in my town, punk.

Yep. That’s right. Rio Bravo — Howard Hawks’ and John Wayne’s well-loved Western — is a direct response to High Noon. Where High Noon is a tense, terse, interpersonal close-up on how we (as Americans) face looming threat, Rio Bravo is an entertaining, expansive, rough-and-tumble Western that gives High Noon the finger. In a technically adroit ‘fuck you’ to Zinnemann and Foreman, Hawks avoided close up shots almost altogether in Rio Bravo. You want to zoom in on the failures of American heroism? Not in my town, punk.

There are four — count ’em four — close ups in the entire 141 minutes of Rio Bravo and none of them are of people.

Like with High Noon, this Western tells the story of a lawman against the odds. Unlike in High Noon, however, this lawman doesn’t particularly need or want your help. That’s because this lawman, Sheriff John T. Chance, is John Wayne.

So yeah. John Wayne. Or Marion Morrison as his folks called him. Lots of folks today turn up their noses when they hear his name, not understanding just how perfectly he spoke to an entire generation. Personally, I love John Wayne. His rolling swagger, his cascading cadence, his unaffected acting style. With the Duke, you get the sense that what you see is what you get. You feel you know the man before you and that counts for a lot when it comes to tallying empathy. He may not be a great actor, but he’s a grand screen presence.

Rio Bravo doesn’t start with Chance, though. It starts with the Dude. I don’t mean Jeff Bridges in a bathrobe; I mean Dean Martin as a drunk. Dude used to be a sheriff’s deputy, but the booze got the better of him. Now he’s a souse haunting the local saloon. He begs for money for a drink and Joe Burdett (Claude Akins), a big-shot rancher’s brother, taunts him by tossing a coin into the spittoon. That’s when Chance shows, kicking the spittoon away from Dude, ashamed for his old friend. The humiliation is too much for Dude who takes his angst out on Chance, walloping him on the head with an axe handle. While Chance is out cold, Joe Burdett pummels Dude. When a bystander tries to intervene on Dude’s behalf, Burdett shoots the man dead.

Rio Bravo doesn’t start with Chance, though. It starts with the Dude. I don’t mean Jeff Bridges in a bathrobe; I mean Dean Martin as a drunk. Dude used to be a sheriff’s deputy, but the booze got the better of him. Now he’s a souse haunting the local saloon. He begs for money for a drink and Joe Burdett (Claude Akins), a big-shot rancher’s brother, taunts him by tossing a coin into the spittoon. That’s when Chance shows, kicking the spittoon away from Dude, ashamed for his old friend. The humiliation is too much for Dude who takes his angst out on Chance, walloping him on the head with an axe handle. While Chance is out cold, Joe Burdett pummels Dude. When a bystander tries to intervene on Dude’s behalf, Burdett shoots the man dead.

Minutes later, when Burdett is at his brother’s place, a bloody Chance shows up to arrest him for murder. And that’s the premise of Rio Bravo. One sheriff trying to keep a lock on one criminal as the whole town stacks up against him. Into this mix we add a few notable faces. Teen crooner Ricky Nelson plays a fast gun called Colorado. Western staple Walter Brennan plays the aged Deputy Stumpy (Brennan was famous for, when being cast, asking if he was wanted “with or without” his missing front teeth), and the lovely Angie Dickinson as Feathers.

Although the odds are long, Chance doesn’t ask anyone for help. In fact, often when help is offered, he refuses it thinking it more trouble than it’s worth. Not that things don’t get hairy, and a lot quicker than they do in High Noon.

Rio Bravo isn’t a political statement, though. While Hawks and Wayne wanted to reestablish the honor of the Western (and American) hero, this film is more about entertainment. It’s like Die Hard in that way — excellent filmmaking aimed at your full engagement. It’s got action and romance and a little singing (Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson, c’mon) and thrills.

Rio Bravo isn’t a political statement, though. While Hawks and Wayne wanted to reestablish the honor of the Western (and American) hero, this film is more about entertainment. It’s like Die Hard in that way — excellent filmmaking aimed at your full engagement. It’s got action and romance and a little singing (Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson, c’mon) and thrills.

In the end, both films conclude similarly. There’s a showdown where the law faces off with the overwhelming threat. Does either man find himself standing alone? What does the man think of the law and justice in the aftermath?

Watch and see: there are, it seems, two kinds of men in Western films.