Last night’s viewing: The Great Escape. John Sturges’ three-hour adventure film is a fondly-recalled boyhood favorite and true story of Nazi-needling bravura.

Last night’s viewing: The Great Escape. John Sturges’ three-hour adventure film is a fondly-recalled boyhood favorite and true story of Nazi-needling bravura.

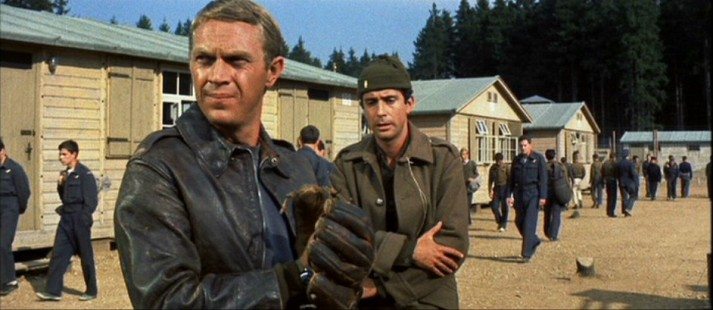

Like Sturges’ other earlier blockbuster, The Magnificent Seven, this is a picture that believes more is more. It’s an all-star cast headlined by Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough, Charles Bronson, James Coburn, Donald Pleasance, and James Garner (many of whom were also in Magnificent Seven). The rousingly unsubtle score, again, by Elmer Bernstein. The story—based on Paul Brickhhill’s non-fiction account of the escape from Stalag Luft III—gets stitched together by popular authors W.R. Burnett and James Clavell. Did I mention that it’s 165-minutes long?

And pretty much a good ride for the whole length, until you end up tangled in barbed wire at the Swiss border with nowhere pleasant to go.

As a film, there’s not a ton to point to in The Great Escape. Sturges is a competent but relatively uninspired director. His scenes run as predictably as prison camp schedules. His cast hits their highs and lows, but we don’t really get to know any of these characters. Excusing the occasional foray into melodrama, most dialogue is business being done. We don’t know who these men are at home or what drives them besides specialized escape knowledge and patriotism. (Richard Attenborough as Big X! James Garner as the Scrounger!)

Donald Pleasance‘s Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe is an avid birder who likes milk in his tea. That makes him stand out as most well-rounded character. Pleasance also manages to give his role something resembling actual humanity while the rest ham it up agreeably.

Or, in the case of James Coburn, ham it up with the least believable Australian accent since English was first spoken at Botany Bay.

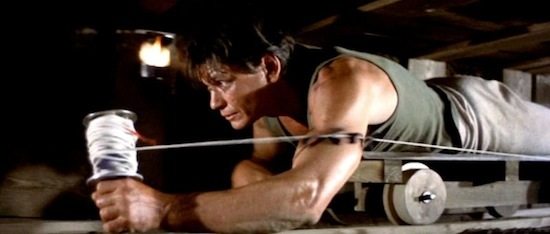

Charles Bronson in one of his more likable roles, as Danny the tunneler. He doesn’t kill a single person in this movie.

Most of what I appreciate in The Great Escape is the thrilling nature of the account. During World War II, the Luftwaffe collected all their most difficult prisoners of war into one camp. These men—serial escapees—recognized their duty to draw Nazi resources from the front by refusing to stay locked up. Instead of popping off in a bunch of minor escapes, however, this group organized a mass break from the Nazi’s newest, most securely built camp.

Speaking of the plan, the adjective “great” doesn’t really cut it. Audacious and crazy are more apt: three tunnels, 30′ deep, over 300′ long each.

As we sprawl into the endless underground warren of the film, it’s difficult not to feel close to Steve McQueen’s Captain Virgil Hilts or James Garner’s Flight Lieutenant Anthony Hendley—both Americans despite no Americans being critically involved in the actual escape from Stalag Luft III. These men are heroic and stalwart and full of exaggerated character. They brew their own moonshine and steal the keys from their own jailers. They are the sort of men that boys wish to be. They are also the sort of men that men recognize as fantasy.

The Great Escape does this strange thing where it takes reality and fantasy and twists them like a soft-serve cone. Our true story of actual war heroism is popularized and pre-digested. Up until the escape itself, it’s hard to deny that this works in proven blockbuster style. While I rarely found myself impressed watching The Great Escape, I was almost always engaged. It is only at the end—as the escape must defend its greatness—that the flavors of this film clash.

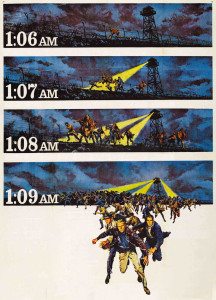

The planning of the escape, and the escape’s execution are great, and both primarily based in fact. The effects of the escape, however, are not great and both not based in fact and horribly real on simultaneous fronts. If you haven’t seen the movie, or if you don’t know the story, the numbers are thus: 250 men attempt to escape from Stalag Luft III; 76 make it through the tunnel into enemy territory—so far, so great. Of these men, only three reach safety (two Norwegians and a Dutchman in real life). Eleven were returned to the camp as POWs. That leaves fifty—that’s five zero—to be recaptured and shot by the SS.

It does not, from what I can tell, seem that the Germans were unduly hindered rounding up the escapees as was the prime point of the attempt. Instead, these real men with real families threw themselves against the wall and were killed for their trouble by a regime too vicious for this film.

Movie Nazis are one thing. Actual Nazis are not so much fun.

I do not mean to question the heroism of the men involved. Being shot as spies was not an expected outcome, although it wasn’t out of the question either. They were, unquestionably, bravely fulfilling their duty as officers. But is this the adventure we want to inspire youngsters with?

I’m not really sure. I recall watching it—and loving it—as a pre-teen but remarking when it ended. “More like the fair to middling escape.”

Fifty men dead. To this Hollywood-ized ‘true’ story they added Americans, a stolen plane, and a motorcycle chase (none of which appeared historically), but they didn’t soften the tragedy of war. The only up note is McQueen’s Hilts being returned to camp so his American friend can toss him his baseball glove before he goes right back into solitary.

Oh those indomitable Yanks! If only they existed.

It’s as if the filmmakers say, “Here’s a great story. We’re sorry the ending is terrible but that’s how it ends. All we can do is make the rest of this flick as enjoyable as possible so you’ll overlook how miserable war and life really are. Now grow up to be Steve McQueen, but one that doesn’t die young.”