Watch the trailer for director Steve McQueen’s new movie, 12 Years A Slave, and you will fear the worst: a weepy, tug-at-your-heartstrings, Oscar-bait Hollywood take on slavery. If you’ve seen McQueen’s previous two movies, Hunger (’08) and Shame (’11), you might hold out hope—maybe he hasn’t gone Hollywood, you dare to pray, maybe his style will come through, maybe I won’t be poked in the eye with a sharp stick for two hours straight.

In Hunger and Shame, McQueen’s style is minimalist, austere and unsentimental, with long, uninterrupted shots. Both movies have a kind of bleakness to them. Michael Fassbender stars in both, in Hunger as an Irishman on a prison hungerstrike, in Shame as a sex-addicted New Yorker. In both he is a man seething with emotions, most of which are internalized. There’s little dialogue. McQueen gets at what’s inside these two characters by creating an atmosphere that highlights their emotions without shouting about them. They are subtly intense movies. They don’t punch you in the head while you’re watching them, but you find yourself thinking about them long after they’ve ended.

Well, thank the almighty cruel movie lords above, because 12 Years A Slave shows McQueen at his stylistic best. It’s his most accomplished work. His unique style is what makes the movie. It is brutal, intense, emotional, and without any sentimentality whatsoever. It eschews the self-important, boring pretension of Lincoln, and the inept, cartoonish violence of Django Unchained. If anything, it might turn off some viewers by its refusal to pander to them in the way they’ve long been accustomed.

How great is 12 Years A Slave? Let’s put it this way: Hans Zimmer does the music, and it’s still awesome. Who could have imagined Zimmer using subtle music cues? It’s a minor miracle.

It’s based on a book, Twelve Years A Slave, written by Solomon Northup in 1853, about his experience of being kidnapped and sold into slavery. A best-seller at the time, it disappeared for about 100 years before being re-discovered in the 1960s.

Northup is played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, from Children of Men and various other movies, including Spielberg’s previous slave epic, Amistad. Ejiofor is incredible. McQueen says he developed the movie knowing no one but Ejiofor would play Northup, and it’s clear why. Like Fassbender, who appears as a plantation owner, Ejiofor is able to communicate volumes with his eyes and nothing more. There is no on-the-nose dialogue telling us what he feels.

At a Q & A with McQueen following the screening I saw, he was asked whether he considered using voice-over, like so many who adapt books for the screen. Bless his heart, McQueen laughed dismissively, and said something like, “No voice-over. Ever.” Voice-over is truly the worst crutch ever invented. Its use in book adaptations is appalling and ruinous. McQueen understands that film is not a book. Film is about using images to communicate, and this he does beautifully.

In one scene early in the film, Northup makes the mistake of angering one of the slavers, played with greasy plausibility by Paul Dano. He and two of his buddies string Northup up in a noose, the rope flung over a low-hanging tree branch. They tie off the rope and yank on it, when the plantation boss arrives and with gun pointed tells them to back off. They run away, releasing the rope. But it’s still tied off, the noose still tight around Northup’s neck. His toes just reach the muddy ground, enough to keep him from hanging. By about an inch. We cut from the boss back to a wide shot of Northup hanging and—and that’s the end of the scene in any other movie. Cut.

Not in this movie. The shot doesn’t end. We just sit there staring at Northup hanging, his toes trying to find purchase in the mud. And then—then nothing. No cut. We’re still staring at him. It’s one of the most uncomfortable moments I’ve ever seen in a movie. And then? Then in the background, now that the drama of a lynching is over, other slaves exit their shacks, and go about their business. They’re not dumb enough to untie Northup; they’d be strung up themselves for interfering. It’s agonizing.

McQueen loves tableaux like this. He shows us an image, then stays with it, giving it more weight than all the fast cutting and overwrought dialogue in the world could equal.

Towards the end comes the most brutal, emotional, wrenching scene in the movie, a whipping. It’s presented in one uninterrupted shot, as carefully choreographed as anything in Gravity, but limited to four characters standing all within 15 feet of each other, the camera going from one to the other, moving carefully around them as the scene builds in intensity. It’s overwhelming.

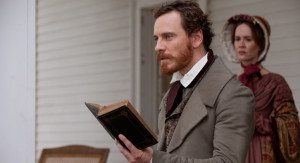

Fassbender gives yet another brilliant performance for McQueen as the plantation owner, Epps. He’s sadistic and cruel, yet falls in love with one of his slaves, Patsey, played by newcomer Lupita Nyong’o. Not that Epps would ever admit his love for her, not even to himself. That he loves her creates a split in his soul he has no ability to understand. He takes it out on her, and everyone else, with violence. Yes, he’s a terrible man, but if anything, he’s to be pitied, unable to grasp what his belief system has done to him.

The slavers treat their slaves as inhuman, but what the movie shows is that it is the slavers who through this process lose their humanity. Brad Pitt appears as Samuel Bass, a Canadian abolitionist (in what is the least convincing performance in the movie, alas), who explains to Epps as clearly as possible why slavery is an absolute wrong. It’s not so much that Epps disagrees with him as that he can’t even comprehend what Bass is saying. They might as well be speaking different languages.

Northup’s experiences are necessarily episodic. The title of the movie is important. You wouldn’t know how long he was gone otherwise. “Some number of years,” is all you would be able to surmise, until at the end you see his family and how much they’ve aged. Which isn’t a spoiler, people. He lived to write his book, after all.

But the episodic nature of the movie isn’t a drawback. There’s nothing boring about 12 Years A Slave. You want to know what happens next, always. Every scene presents a new horror.

I’m curious to see how it’s received. Going back to what I wrote at the start, audiences are used to being pandered to in a very specific way by movies like this. Will they respond to one made with such restraint? They expect to be hit over the head with a two-by-four, told when to cry, when to cheer, who to hate, who to love. Nobody’s perfect in this movie. They are all just terribly human, caught up in a system that destroys all who enter it, whether by choice or by force. That Northup escapes with some measure of humanity left to him is in itself stunning.

Much like Hunger and Shame, 12 Years A Slave is the kind of movie that grows more powerful the longer it sits with you, more so, I think, with its larger scope and historical setting. McQueen and writer John Ridley have turned what in the hands of pretty much anyone else would have been a safe, sappy, limp look at the woes of slavery into an unsentimental, beautifully shot, simple and powerful movie. Let’s hope it finds the love it deserves.

Ha! Love the line about Hans Zimmer.

To be fair, there are some very loud Zimmerisms in there, but they feel appropriate.

So happy to hear McQueen hasn’t gone Hollywood.

I couldn’t be any more excited to see this movie now…

Almost as excited as I would be to travel back in time to see Lawrence of Arabia with you, SB… and then go to El Pavo for a burrito… and then play cards…

That would indeed be a pleasure. Although seeing as we’d have a time machine, we’d have to think of a few other things to do too.

Great review. I’m looking forward more than ever to see this.

Just watched this yesterday. The two scenes mentioned above were the clear standouts for me but aside from those overall It fell a bit flat for me.

A kind of flat quality is, I think, a conscious part of McQueen’s style. Which isn’t going to make you like the movie any more, of course, but it’s interesting to watch all of his films with that in mind. He works with hugely intense emotions, yet renders them well below the surface. I think that style pays off huge in 12 Years, less so in Shame.

Yes I remember that from Hunger, I’ve not watched Shame. I can’t quite find the words for what was missing for me right now, I feel like he presents the story but doesn’t interrogate it. The two scenes mentioned are standouts; especially the hanging scene, that could almost be an art installation just playing on a loop, it just says so much.

Having just watched it, I can add that Shame is the weakest of the three, but still compelling in its way. Plus, Fassbinder makes some impressive orgasm faces.