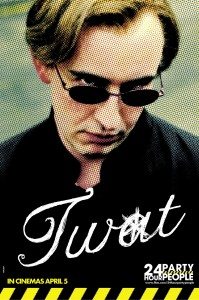

’24 Hour Party People.’ This is, I learn, a song by the Happy Mondays, which were in turn an important band in the Manchester music scene of the 1980s and ’90s. I’d heard of the Happy Mondays but I hadn’t really ever heard them. Nor, really, had I heard much Joy Division or New Order or many of the other bands that feature in Michael Winterbottom’s film 24 Hour Party People.

’24 Hour Party People.’ This is, I learn, a song by the Happy Mondays, which were in turn an important band in the Manchester music scene of the 1980s and ’90s. I’d heard of the Happy Mondays but I hadn’t really ever heard them. Nor, really, had I heard much Joy Division or New Order or many of the other bands that feature in Michael Winterbottom’s film 24 Hour Party People.

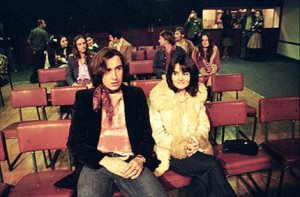

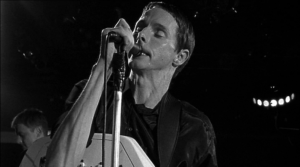

Now that I’ve watched Winterbottom’s film, though, I know a bit more about the music explosion in ‘Madchester’ as channeled through and around Tony Wilson (played by Steve Coogan) and Factory Records. I know that Ian Curtis, lead singer of Joy Division (Sean Harris) danced like a herky-jerky man; I know that the Happy Mondays did a lot of drugs; and I know that Andy Serkis (as record producer Martin Hannett) looks not too much worse digitally disguised as Gollum than not. I have a sense of what happened in the ’80s Manchester club scene, but only in the way I have a sense of what string theory is all about.

Watching 24 Hour Party People is like getting invited to a party at which you know nobody, but at which you feel you might want to do a bit of schmoozing. By the end of the night—two hours long and not, blessedly, 24—you’ve had an interesting conversation with a couple of revelers and maybe got a number or two. In my case, that number was for Joy Division, whose album ‘Unknown Pleasures’ I am now listening to for the first time.

I can’t say I really like it, even though it and your t-shirt replicating its album cover were seminal factors in your youth.

It doesn’t have that one great track, ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ on it, and I didn’t realize—even after watching 24 Hour Party People—that that song isn’t on one of their two albums. Because, spoiler alert, Ian Curtis failed to choose life.

So it’s like I went to a party where I knew no one, got a number, but when I called it, it turned out to be for a cab company.

All this doesn’t mean there isn’t substance or style to 24 Hour Party People. Winterbottom and screenwriter Frank Boyce let Coogan’s caricature of Tony Wilson wander freely from grey reality in order to illustrate myth, accentuate occurrences, and crack wise in that dry Coogan manner. It’s chocko with cameos who get introduced after the fact in 4th-wall-breaking asides. The fact that I recognized almost none of these people or their names lessened these thrills.

Because 24 Hour Party People is likely a fantastic film for people who would recognize the name of a Happy Mondays song. It is the history they lived or imagined brought to fanciful, occasionally delightful life; it is a celebration of all they adore. It is also a fairly lousy introduction to these personages and this music and that time.

It’s an in joke. It’s a behind the scenes video to a movie that I haven’t seen.

What I did like about 24 Hour Party People is the way they liberated a true tale from the mundane constraints of fact. History—particularly entertainment history—isn’t fact. It’s subjective story. Whether it’s being recited by an announcer on the news or related by a drunk at the pub, it’s warped and always will be. This is true even though when filmmakers recreate a scene and make up dialogue, you forget to question it. People watch films such as Oliver Stone’s J.F.K. and don’t know where semi-real ends and utter bullshit begins. That’s not the scene here.

In 24 Hour Party People folks converse with God and see UFOs and shag in the bathroom. It doesn’t much matter if that stuff really happened or not, because the film is—happily—not about facts. It’s about a moment in time. So again, it’s like a party where you don’t know anyone. You’ll tell five different people seven different stories about what you do, and who cares if any of them are true. Maybe they get to know you a little bit, and perhaps they even want to get to know you better.

Winterbottom steps lively around Manchester and music icons. He fires guns at the wall and cuts real footage of shows with shots of staged audiences and snorts the white line down the middle of the road. Often I really enjoyed watching and listening to this romp. Just as often I got bored.

I never really knew what it was that made these people or those moments or any particular musical performance important. Tony Wilson has some fanciful ordeal interviewing someone he calls the ‘Mad Monk,’ for example. It took me ten minutes of research to figure out who this guy was (Sir Keith Joseph, Conservative politician) and what he had to do with anything (not much).

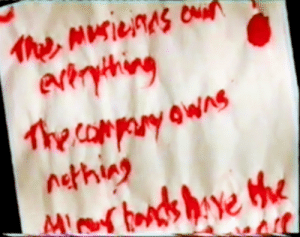

Did Wilson really only have a contract with his bands written in his own blood that denied himself any right to anything? I think so. Did Happy Mondays singer Shaun Ryder (Danny Cunningham) really sit on a rock off Barbados and refuse to write any lyrics? Probably not. But he might have held the master (and vocal-less) master tapes for their next album hostage for 50£. Too crazy to be true or too crazy not to be true? One of those, probably.

Now I’m playing the Happy Mondays, I’m surprise to dig them. Based on the film, I thought they were a bunch of drug-addled tossers.

Which they might have been.

But it would be hard to know for sure just by watching 24 Hour Party People.

I have a dim, hazy memory of more or less enjoying this one, and liking Steve Coogan in particular. Winterbottom makes some curious movies.

It was much better than Velvet Goldmine, that’s for sure.

So you don’t know anything much about Manchester and it’s music scene, Joy Division, New Order, Happy Mondays, or anything much, and you’re not sure if things depicted in the film are true, though it is clearly based on real events, and narrated as such. Well, this is why the film is there – to tell the story. Yes, Wilson really did write the contract in blood that said they had no rights, yes, Shaun Ryder did refuse to write lyrics in Barbados, and may or may not have sat on a rock (that scene was clearly a parody). Do I really have to spell everything out for you? What a lazy, lazy review.

No CB. You don’t need so spell everything out for me, even when commenting on a (checks notes) seven-year old review. But I wasn’t reviewing the Manchester music scene; I was reviewing this film. Which I don’t much remember. Re-reading the review, however, I feel I was honest about what it did and didn’t do for me. Is that lazy? Or are you just irked that I don’t love what you love?

If it makes you feel any better, I’ve since grown to appreciate Joy Division (and never listen to the Happy Mondays).