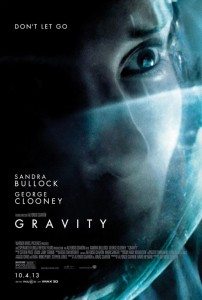

It is inevitable. What goes up must come down. That is the effect of Gravity, the new film from Alfonso Cuarón—director of the stunning Children of Men—starring America’s sweethearts Sandra Bullock, George Clooney, and the planet Earth. The movie is an acrobatic tumble through an orbit too low to last. The pull of planetary forces refuse, eventually, to let the picture go—but what a ride!

It is inevitable. What goes up must come down. That is the effect of Gravity, the new film from Alfonso Cuarón—director of the stunning Children of Men—starring America’s sweethearts Sandra Bullock, George Clooney, and the planet Earth. The movie is an acrobatic tumble through an orbit too low to last. The pull of planetary forces refuse, eventually, to let the picture go—but what a ride!

While it lasts, particularly in IMAX 3D, you spin as high as possible. There is none higher. From its opening perspective working on the Hubble space telescope as docked with the space shuttle Explorer, there is virtually no direction to go but down. Veteran astronaut Matt Kowalski (Clooney) zips around with his jetpack and talks of west or north but those terms are preposterous in space. Filling half the sky that is no sky, we are confronted with the magnitude of our planet. Virgin astronaut and some sort of technical bio-med whizz, Dr. Ryan Stone (Bullock), feels ill as she tries to make her special whatsit work on the Hubble. We feel ill, too; disoriented and spun as Cuarón shows off his mad skills constructing space.

The first shot does not end. It twirls and dives and grasps in a way reminiscent of Children of Men‘s auto ambush. You can watch a good chunk of this beginning online. You can also watch the drama unfold as satellite debris does a drive-by, turning the Explorer and the astronauts into Sonny Corleone. Here is our story: Dr. Stone ‘off-structure’ and spinning free in space. Lt. Kowalski to the rescue.

Gravity puts you in space in a way few other films have managed. My experiences as an astronaut are too brief to mention, but everything—at least technically—was wholly believable to my eye. The film starts with an unnecessary bit of title reminding us that space is cold and devoid of oxygen and unfriendly to sound. And then you’re in it. You are in space, connected to a bit of metal by a strip of fabric, and floating. Invariably you will think of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Gravity puts you in space in a way few other films have managed. My experiences as an astronaut are too brief to mention, but everything—at least technically—was wholly believable to my eye. The film starts with an unnecessary bit of title reminding us that space is cold and devoid of oxygen and unfriendly to sound. And then you’re in it. You are in space, connected to a bit of metal by a strip of fabric, and floating. Invariably you will think of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

This is intentional. Cuarón clearly references the end of that film in one shot here, but it is a mistake. While Gravity looks absolutely stunning and feels frequently captivating, its reach into meaning is considerably less poetic than Kubrick’s. For a start, the script for Gravity, co-written by Cuarón and his son Jonás, is full of grand first ideas. They are the sort of ideas that a writer comes up with to build what could be an everlasting story, and which he or she then sets aside to touch points less obvious and facile. Lt. Kowalksi, as an example, is the sort of man who always has a rambling story to tell. He is the sort of man who deals with his abandonment in space without emotion. He is the type of guy who looks his dead colleagues in the eye and offers nothing in response. These dead men and women—this life I have—it is nothing to me but a rambling story. That sounds nice conceptually but works poorly in practice.

It is not that George Clooney is bad as Kowalski, or that Bullock is particularly bad as Stone; it is that their characters are not grounded by the sort of gravity this films lacks.

It is not that George Clooney is bad as Kowalski, or that Bullock is particularly bad as Stone; it is that their characters are not grounded by the sort of gravity this films lacks.

I dare you to watch Gravity without feeling yourself immersed in the calamity these characters face. That is the sort of praise the film deserves. I also dare you not to question the honesty of their responses and their dialogue as the disaster unfolds. They are not wrong per se; they are just not right.

While there are few films out now (or ever) that match Gravity‘s heights, it is easily surpassed in depth. The story is dual. We track Stone’s struggle for survival and we track her journey to get her feet beneath her once again, metaphorically. This metaphor is wispy. Its underpinnings are weightless, as if they are also lost in space. So, in Gravity, we get a novel and captivating disaster film, but not much to consider when the day is done. That’s gravity but not so much gravitas.

You feel Cuarón reaching for the stars, but they are so far away. It is like throwing a rock at the moon. His arm is exceptionally strong but I have concerns about his aim.

You feel Cuarón reaching for the stars, but they are so far away. It is like throwing a rock at the moon. His arm is exceptionally strong but I have concerns about his aim.

It may be unfair to compare Gravity to Children of Men and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Both of those films will be watched and remembered for as long as we have cinema. Compared to other films—to Argo or Pacific Rim or Elysium—this one is far superior. It is unquestionably breathless and agoraphobic and untethered. It ended and I was glad to have stayed up late for an opening night IMAX screening.

Technically, it is like Avatar except not infuriatingly stupid and banal. Visually, it is as close as you are going to get to hitting the moon with that rock. Its humanity may be overly removed by protective gear, but you’ve got your own humanity. Go see Gravity and bring it with you.

You know, I totally bought Clooney’s dialogue. His self-satisfied yapping (before the disaster) transitions seamlessly into his paternalistic, controlling optimism as the crisis unfolds. I believed that the way that man stays sane in that situation is to have somebody else to be Important and Necessary for, to be a rescuer, to sort of close his eyes emotionally and let his narcissism guide them through. I thought he was deftly written, considering that his character is necessarily a sketch-length composition. His echo into Bullock’s later journey hinges on believing in his character at the beginning and, yeah, I totally bought it.

And also, I walked around all last night feeling like if I didn’t crank the right valve or get a death grip on the right protruding crossbeam, I would be gone forever. Can’t remember the last time a movie stayed with me so intensely after I left the theater.

This, of course, is very good news. I’m glad you bought into Clooney’s character in a way I did not. I’ve read some defense of the sketchy nature of the characters in Gravity, and… yeah. Not really buying it. I don’t think they’re broken or bad, I just didn’t see the fine tuning which clearly was given all of the visual elements.

For example, Clooney sets himself loose to die in space because “the rope won’t hold” or something. But that’s not clearly the case. And what’s more, by trying to survive himself he would exponentially increase Bullock’s chances of surviving—something she really has no right to do in the first place. It’s a dramatically effective scene. It just isn’t particularly believable.

And in a film in which everything you see is so believable, having characters behave in ways or say things that are just a little out of tune colors the overall effect.

That makes the difference between a film I leave grooving on and a film I leave thinking about.

But I also liked Gravity. I just liked it in a qualified way. I would have preferred if Clooney was afraid to die, just a little, so I could feel and empathize with his fear. That would be human and believable.

Though I didn’t really buy Clooney as a real person, that didn’t really bother me. Like Frontalot, I thought the character worked for what he had to do.

On the other hand, his floating away moment was kind of baffling. Was their orbit so low that the earth’s gravity was tugging him down but not tugging Bullock? Why didn’t she just yank him towards her? Eh…I’m no physicist. Did seem a bit convenient. For the story. Not so much for Clooney.

What bothered me was more Bullock’s chatting to herself alone later in the movie. The whole thing with her daughter felt so unnecessary and on-the-nose. I mean she’s struggling not to float off into space and die. How is that not metaphor enough? Plus they kept cranking up absurd music cues at those points, when for much of the movie the music is really low key and atmospheric.

Also at the very end Bullock repeats just about everything Clooney said to her earlier, it felt terribly contrived, and really took me out of the moment–which moment was her almost burning up on re-entry. Which I’d say is plenty exciting without her babbling like that.

But yeah. The direction and cinematography and CGI are unbelieveable and should be seen by all humans on very big screens postehaste.

I just saw it and I was bored. At the beginning, I was pulled in immediately by the visuals and the nifty camerawork, but once the story started moving, I had more and more trouble with it. I agree about the lack of gravity. I thought Bullock did fine and her emotions felt real to me. Clooney left me high and dry, however. The dialogue was indeed often terrible. And, yes, Clooney having to untether himself defies the laws of physics. There was no force pulling him away.

Also, notice the way they characterized the three nationalities? The American ship gets a Marvin the Martian. The Russian ship gets a chess piece. The Chinese ship gets a ping pong paddle! I thought that was hilarious, but in a pathetic way. (Unless it was supposed to be funny, but even then it’s pretty offensive.) And why on earth would a Russian space station have a computer that flashes the word “FIRE”?

As for story, I thought it was all too thin. They tried to beef it up with Ryan’s need to overcome her fear of living, but it was way too forced. There was very little to think about. Just a series of obstacles for her to struggle through. Very pretty, but no substance.

Or are we supposed to think that she was thanking God at the end? Remember she complained that nobody had ever taught her how to pray, and she keeps talking about seeing her daughter. She believes, or she’s struggling to believe. And then, to get the strength to finally stand, she says, “Thank you.” So maybe this is really a movie about her leaving science and finding religion? Getting her feet back on the ground, on Mother Earth, is a metaphor for returning to God. Maybe?

Basically, I think this film has the same emotional effect as watching a motivational speaker, but with much better special effects.

I believe the ending (and the film) was meant to symbolize the process of (re)birth and evolution. She ‘stands on her own’ again. It’s a fairly straightforward symbol for a fairly straightforward film.

Rebirth, I see, but evolution? I just wrote something: Gravity is about Finding God.

Yeah. I don’t know why I said evolution.

But I read your piece. Good points. I’m not sure I see the faith in Gravity or the science, though. I think it’s just a simple story of a woman deciding to live; so basically it’s The Grey in space. She is in a vacuum following the death of her daughter. Life is difficult and she resists its pull. Through the course of the story, she reacquires her will to live and allows herself to be carried back to the world, where she finally stands on her feet again (after emerging from the amniotic Lake Powell).

Then she is eaten by a giant crocodile. Or at least that’s what happens in my imagination.

Not faith in gravity, faith in God. Gravity is religion, what brings her to God (earth) and keeps her feet on the ground. But she needed a leap of faith to get there. I don’t think we can ignore all the stuff about prayer and an afterlife. But I agree it is a very, very simple story about a woman deciding to live, against all odds. It’s just that she needs religion to get there. They could’ve taken out the religion stuff and made it slightly leaner. It wouldn’t have changed the structure of the plot at all. It just would’ve meant less dialogue. It would’ve been better. But I guess people like the religious stuff.

The point about science is weaker–the movie isn’t necessarily saying that science brought her away from God. Clooney’s character might represent a different kind of scientist–an old-fashioned, more human kind of scientist. But I think it is suggesting that science can take people away from God, even if doesn’t have to.

It’s an interesting interpretation but it seems like a stretch to me. I think religion is just part of life (for many) and it’s an element of this film, not the point.

So why is it called “Gravity?” The religion interpretation just makes so much sense. She has a vision of her fallen comrade, learns how to pray for the first time, takes a leap of faith . . . I don’t think it’s a stretch to take take these elements of the story seriously.

I would say that gravity does not symbolize organized religion, or institutional religion . It represents personal religion, finding the faith necessary to save oneself. The spiritual aspect of Ryan’s journey can’t be ignored, though it can be downplayed. You can interpret it as a purely psychological phenomenon–where spirituality is a useful condition which helps people overcome obstacles and be successful. Or you can treat it as a supernatural phenomenon, where people are literally connecting with some higher power. Either way, it’s about personal religion.

Another nice contrast I just noticed, on reflection: the cold of her loneliness and desolation is contrasted with her willingness to “burn up” in her descent to earth. She’s embracing fire instead of ice, life instead of death. It’s an effective metaphor. But fire is also suggestive of a trial. She does not have faith that she will survive, but she has faith in her purpose. Fire = life = a trial which tests our faith.

I don’t think you can avoid the religious connotations, and they’re very Catholic. There’s also a lot of religious symbolism in “Children of Men,” which Cuaron has acknowledged, though apparently he wanted to avoid dogma. It would be surprising if he did not intend the strong religious symbolism and meaning in this film. I think he has a strongly religious sensibility, but with a critical attitude towards organized religion and dogma. That’s reflected in the way religion is presented in “Gravity”: as recognizably Catholic and yet entirely personal.

And then there’s the fact that, after she passes her trial by fire, she is baptized in the sea.

You make sense Jason. But religion is one of those things that one can see wherever one looks for it. Religion describes life, so anything that’s about life can be said to be about religion. Choosing to live is ‘religious’ if you’re of that mind. Or, if you’re of a scientific bent, you can interpret reality that way.

When a story is as basic as this one, it’s all too easy to put your own meaning to it. That’s not a criticism.

I don’t look for religion, but I tend to be very sensitive to it . In the movie, there are easily recognizable religious icons. There is much talk about prayer and the afterlife. These are explicit references to religion that I find hard to ignore. I’m not putting my meaning into it. I’m not religious, I don’t think choosing to live is religious.

I’m talking about observer bias, which I have as well. You had the (reasonable) idea that there might be religious themes in Gravity. You looked for evidence and found evidence. Fine.

I’m suggesting if you looked for evidence that there were other themes you’d find those as well, probably. It’s a vague enough film to mean whatever you want it to mean. I’m not saying there aren’t religious elements to the film; I’m saying I do not think the religious elements are the explicit point of the film.

You don’t think choosing to live is religious because you’re not religious. If you were, like maybe the Cúarons, than those explicit references you cite might suggest other things to you about the meaning of life. They may just be part of how a religious person sees the world and speaks about the world, in which case everything a religious person writes or creates has religious themes — because that’s their heuristic.

So maybe I agree with you. It’s about religion as much as everything is about religion, if you’re religious. Which I’m not.

You are welcome and encouraged to have your own interpretation, though. I think I’ve thought about Gravity more than it deserves already.