In 1963 Stanley Kubrick made a list of his top ten favorite movies, the only time he was ever known to make public such a list. It’s got some usual suspects—Citizen Kane, Wild Strawberries, City Lights—and some more idiosyncratic—Roxie Hart?—well, why not, it’s got Ginger Rogers in it, plus Adolphe Menjou, who Kubrick would later cast in Paths of Glory to great effect. But this was in ’63. Presumably his list, like all of our lists, changed yearly, if not daily. In later life he was known to call Lynch’s Eraserhead his favorite movie of all time, and when it first appeared to screen it for everyone he knew.

Number four on his list is John Huston’s noirish The Treasure of The Sierra Madre (’48), the story of three men searching for gold, and learning firsthand its power to corrupt. I don’t think it’d make my top ten, but it’s got to be up there pretty high. Everything about the movie is aces. John Huston won Oscars for directing it and for writing the adaptation (it’s based on the book by B. Traven, which I assume you’ve read, as you’ve read all adventure stories written in ’27), and Huston’s father, Walter, who stars as the crusty old prospector, Howard, won one for Best Supporting Actor. Now there’s a swell kid who appreciates his pa, writing him a role like that.

Walter Huston makes being old and crusty as funny as possible. From the get-go, when he meets Fred C. Dobbs (Humphrey Bogart) and Curtin (Tim Holt), he jabbers away about the wonders and the perils of prospectin’. Why, he’s made and lost many fortunes, because that’s the curse of the gold-digger: no matter how much you make, which only a lucky few make anything at all, you want more, ever more. Which sounds awful nice to Dobbs and Curtin, stuck as they are in Tampico, Mexico, penniless and jobless. Dobbs hits up other Americans for coins, including, in a cameo, John Huston himself, who after having the bite put on him three times running tells Dobbs, “From now on, you’ll have to make your way through life without my assistance.”

Lucky for Dobbs and Curtin, the man who stiffed them on a construction job coughs up their money once they beat it out of him. It’s almost enough to stake them to the supplies they’ll need to make a go of prospecting. Then luck really strikes: Dobbs wins the lottery! He bought one twentieth of a ticket, and it pays just enough to get them funded.

One of the joys of Treasure is that much of it was filmed on location in Mexico, something nobody in Hollywood did back then. “Location” meant “which backlot” in them days.

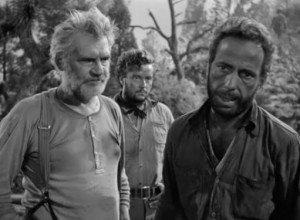

So off our heros trek into the mountains, the relative youngsters Dobbs and Curtin barely able to keep up with Howard, who skips up the mountains like a goat. Sure enough, they find gold ore, and it’s not all shiny and lumpy, it looks pretty much like sand, unless you know what you’re looking at, which Howard does.

Soon enough they’ve got enough gold that each man holds on to his own third, and poor old Dobbs starts growing paranoid and crazy, just as Howard always said happened to folks once the gold starts piling up. Howard and Curtin aren’t immune to the paranoia, but unlike Dobbs, they’re smart enough to keep calm and work together.

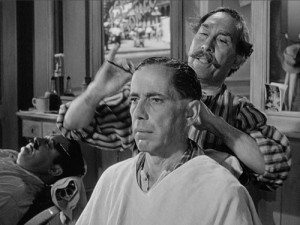

Bogart gives a deranged performance as Dobbs, bearded and dirty and talking to himself. Maybe one has cause to think this when watching anything starring Bogart, but damn is he ever a weird looking guy. How could anyone so odd become a movie star? In the beginning, in Tampico, when he gets himself cleaned up with a shave and a haircut, he actually looks weirder still.

Trouble finds our paranoid friends eventually, first in the form of a lone American looking to horn in on their find, and later in the form of banditos, who deliver the famous and oft mis-quoted line, “Badges? We ain’t got no badges. We don’t need no badges! I don’t have to show you no stinking badges!”

The dialogue throughout is dynamite. Huston is a tremendous writer, as so many of his movies show. He’s also willing to push as hard as he can against the limits of the era. In one scene around the campfire, Curtin and Howard speak of what they hope to do with their money. Howard wants to live the rest of his life in comfort, and Curtin wants to start a peach orchard. When Dobbs is asked what he wants, it’s all Turkish baths and fancy clothes and enormous feasts. “And after that?” asks Curtin. “What else?” says Dobbs, and gets a faraway look in his eyes, and Curtin gets one in his, and we in the audience can see the salacious thoughts running through their heads. Howard breaks it up with, “If I were you boys, I wouldn’t talk or even think about women. T’aint good for your health.”

It’s a violent movie, too. A lot of people die, they’re shot or even hacked up with a machete. It’s not often you can look at a movie from ’48 and feel that it presents the world close to what it might have been like. Or as close as movies ever come, anyway. It feels real, is the point.

In the end, who lives? Who dies? Who gets the gold? It’s impressively up in the air. All you know for sure is that whatever happens, it ain’t gonna be purty when the theme is “money corrupts.”

Which theme may not be the most astoundingly original–it’s not exactly breaking news–but has any movie done it better? Richard Pryor in The Toy, perhaps? No. And I can think of no other contenders, not having had lunch yet. There was Sam Raimi’s movie A Simple Plan, about three dolts who stumble on a bunch of money and slowly but surely screw everything up. What annoys me with that movie is the “dolts” part. Three idiots find money, make stupid decision after stupid decision, and end up dead or in jail or broke or whatever. And I thought, so what? What does that say? Stupid people are stupid? Money makes stupid people really stupid? What would be interesting would be three smart people finding a bunch of money, making smart decisions, and still winding up dead or broke or in jail.

In The Treasure of The Sierra Madre, the three prospecters aren’t stupid. They don’t make bad decisions, not until paranoia drives Dobbs mad with greed. Gold turns him stupid. He doesn’t start out that way.

Kubrick does the same thing in his classic noir, The Killing. Nobody’s stupid. The plan is foolproof. It’s only foiled because one character, browbeat by his conniving wife, lets slip what he’s up to, and from there it all spirals out of control. Pull one thread, and the whole thing unwinds.

In Treasure, Dobbs is that thread. Once he unwinds, everything falls apart. And that, my friends, is the kind of thing that makes for entertaining cinema.

I gotta see this soon.