It’s halloween, and you know what that means: zombies, werewolves, vampires, sexy French maids, and other horrible monsters roaming the streets, begging for sugary handouts, and possibly devouring your brains and/or giving your living room a light dusting.

Here at Stand By For Mind Control we could recommend a pair of horror flicks for your halloween double feature viewing without breaking a sweat. In fact we already have. Pi and Seconds will leave you huddled in the corner, clawing the wallpaper, insisting you’re not insane. Island of Lost Souls and The Island of Dr. Moreau are full of hideous monsters, and I’m not just talking about Marlon Brando and Val Kilmer. The Last Man On Earth and Night of The Living Dead are the original two vampire/zombie classics, each starring hordes of the undead. Frankenstein and Rosemary’s Baby are two perfect halloween standards from different eras. And of course Blue Velvet and American Psycho fully delve into the terrifying nightmarish deathscape that was the 1980s.

We could recommend any of those. And we do. Hell, we could just tell you to watch The Shining again and our work would be done.

But we’re not taking the easy way out. For this week’s halloween-themed Mind Control Double Feature, we turn to two documentaries to ask a simple question: what could be more terrifying than being accused of a murder you didn’t commit? Tried and found guilty? Locked away for years on death row, awaiting your turn on Old Sparky? There’s a horror story for you. The kind that’s all too real.

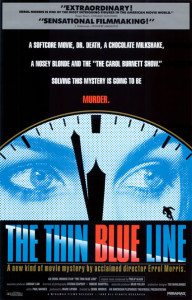

The Thin Blue Line (’88)

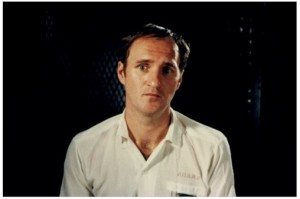

When documentarian Errol Morris showed up in Texas in ’85 to make a movie, it wasn’t going to be about convicted murderer Randall Dale Adams, who’d been sitting in jail for nine years of a life sentence (Adams was supposed to have been executed in ’79, but his sentence was commuted at the last second). Morris was there to interview Dr. James Grigson, AKA Dr. Death, so called because he was known to testify that any man accused of murder was sure to kill again, a finding required if the accused was to be sentenced to death. A useful man for prosecutors, not so much for the accused.

Dr. Death turned out to be awfully boring. But when Morris interviewed some of the men his testimony had sent to death row, he came upon Adams. Once he’d heard the baffling story of Adams’s arrest and conviction, Morris had the subject for what would be his third film.

And what a film it is. Morris had worked previously as private investigator, and used those skills, along with those of the filmmaker, to find and interview everyone involved in the case, and to reconstruct the alleged murder.

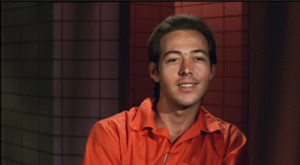

It starts off simply, with a man, unidentified, speaking to camera. We come to understand that this is Adams. Morris’s style is simple and brilliant. Or rather, its complexity creates the feeling of simplicity. Subjects talk, but there are no questions heard. No one is identified with subtitles. It is only through the juxtaposition of interviews that we understand who is talking and who they’re talking about. Piece by piece, a complete picture of events is built. So to begin, Adams says while hitch-hiking he was picked up by 16 year-old David Harris. Cut to Harris, who takes the story from there. And so on. The film is an expertly woven tapestry.

The crime: two cops pulled over a car one night. One approached the driver’s window. The driver shot the cop to death from within the car, and sped off. Harris, later picked up by police, claimed he was in the car with Adams, and that Adams shot the cop.

The case, as it unfolds through the re-telling in The Thin Blue Line, is stunning. You watch it thinking, how could this man have been convicted? The abuse of power on display is appalling. The prosecuters and the police want only one thing: to convict someone for the crime. Whether or not it’s the right someone is beside the point.

Morris used a technique in The Thin Blue Line that in ’88 was unheard of in the world of “real” documentaries: he shot a few re-creations of what happened, primarily the murder, and, over and over again, the car pulling away. Morris was accused of bastardizing the documentary form by shooting not only what “is,” but also “what might have been.”

Of course today this sounds insane. You can’t watch a television doc without half the damn thing featuring actors re-enacting what “really happened.” How times change.

The Thin Blue Line sweeps you up in its story with a slow, inevitable build, pulling you in without forcing the matter, and by the end leaves you aghast at what was done to Adams. Philip Glass wrote the music, and it is, as always, totally mesmerizing.

So powerful and convincing was the movie that within a year Adams’s case was overturned by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and sent back to Dallas County, where the DA declined to reprosecute. Adams was released in ’89. The movie saved him.

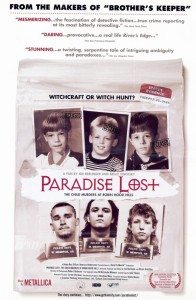

Paradise Lost: The Child Murders At Robin Hood Hills (‘96)

While The Thin Blue Line’s story is told with a kind of dispassionate, investigative, logical puzzle-building, the story of Paradise Lost is presented as the most ghastly, appalling nightmare you will ever experience.

Made by documentarian duo Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, Paradise Lost tells of two tragedies at once, and it’s hard to say which one is worse by the time the movie ends.

The first tragedy is the crime that starts it off. In ’93, in the evangelical Christian community of West Memphis, Arkansas, three eight-year-old boys are found murdered, naked and tied up with shoelaces, in a creek. The parents are devastated, the town is in shock. The police begin an investigation, but there’s little evidence to go on.

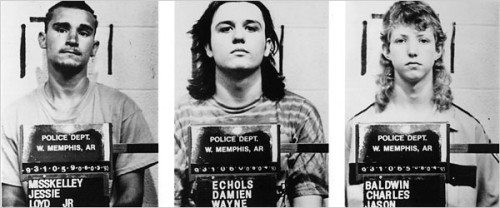

The second tragedy is what happens to the three teenagers the police eventually accuse, arrest, and try.

The murdered boys appear to have been sexually mutilated. As experts at the trial would later claim, they were ritualistically mutilated. The perpetrators, then, were clearly part of a Satanic cult, one led by accused ringleader, Damien Echols.

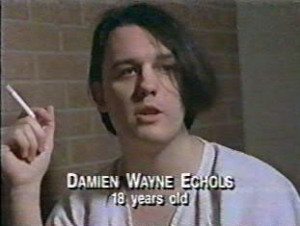

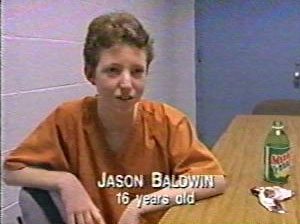

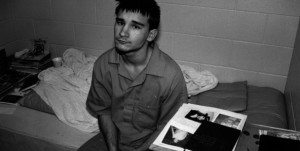

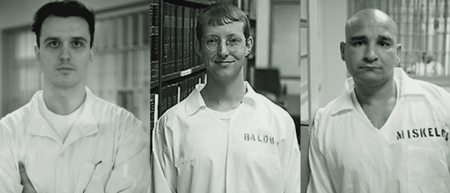

Echols made the mistake of dressing in black, listening to the wrong music, and being interested in the wrong books. He was an obvious target. His best friend, Jason Baldwin, didn’t wear black or write morbid poems, but he also made a mistake: he was friends with Damien. The third accused teen was Jessie Misskelley, a borderline retarded boy with little connection to the other two.

As the movie unfolds, the case against the three boys appears more and more ludicrous. You simply can’t believe that anyone truly interested in solving the crime would settle on them. One of the murdered boys’ fathers, John Mark Byers, preaches death and doom to the accused, and by the end of the movie you can’t help but suspect he’s the real killer.

Misskelley is interrogated until he “confesses.” Too bad the bulk of the interrogation wasn’t taped by police. Convenient. He accuses Damien of being the murderer and of Jason joining in. The confession “leaks” to the papers. That Damien and Jason are guilty becomes common knowledge.

And as for Satanic cults? Back in the late ’80s and ‘90s, the idea that Satanic cults were everywhere, committing hideous acts of evil, was commonplace and taken as fact, despite zero evidence showing it to be true. An “expert” in such cults testifies at the trial. His credentials? He has none. But he’s made a lots of informative videos for police across the country.

Most usefully, cults kill children for their rituals. So indeed it makes perfect sense that the accused didn’t know the victims and had no rational reason to wish them harm. They must have done it.

It’s as grim and scary a movie as I’ve ever seen. Metallica allowed their music to be used (Damien was a fan), and it adds to the inevitable doom of the proceedings.

When the trial of Damien and Jason finally concludes (Misskelley is tried separately), you simply can’t believe any sane jury would find them guilty. The case against them is all circumstantial. There isn’t a shred of evidence. It’s a joke.

The jury is unanimous. Guilty. Jason to spend his life in prison, Damien to be executed. The film ends as the two are chained up and led away. You want to scream and tear your hair out. You can’t even call it a miscarriage of justice, because there’s no justice to begin with.

Paradise Lost is one long nightmare from which you can’t awake.

(And now—a very long parenthetical addendum! Hooray! Documentaries are just so full of information, ain’t they?

Like The Thin Blue Line, which saved Adams, Paradise Lost was so affecting to all who saw it that a huge grassroots campaign to free the so-called West Memphis Three arose. Supporters included filmmakers Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh, and musicians Eddie Vedder and Henry Rollins, and actor Johnny Depp.

Sinofsky and Berlinger made a sequel four years later chronicling those efforts and showing the effects of prison on the convicted “murderers.” It also lays out a case for John Mark Byers being the real killer. (Unfortunately, that case is about as circumstantial as the one against the West Memphis Three, and likewise relies on the fact that Byers just kinda seems like the one who did it.)

It took eighteen years, but the efforts paid off. The West Memphis Three were freed in 2011, taking the rarely used Alford Plea, where they maintain their innocence while pleading guilty, meaning the state and the D.A., lying sacks of shit that they are, can still say they got the murderers.

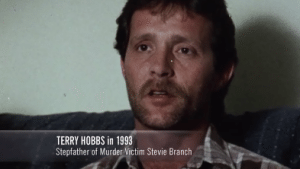

Which is a terrible joke, because in Sinofsky and Berlinger’s third Paradise Lost movie, which relates the Three being freed, they first off apologize to Byers for the second movie, then lay out the case that Terry Hobbs, stepfather to one of the other murdered boys, is the one who did it, this time based on actual evidence. It’s damning.

Amy Berg also made a documentary in 2012 about the entire history of the case, West of Memphis. It lays out the case against Hobbs even more thoroughly; even his relatives have come forward claiming that Hobbs admitted to the crime. But as far as the state is concerned, they’ve already got their killers. Case closed. And so Hobbs walks around as free as he’s been for the eighteen years the West Memphis Three spent behind bars.

Berg’s movie is more of an overview, and a bit self-congratulatory. If you’re enthralled by Paradise Lost, it’s worth the time to watch the sequels by Sinofsky and Berlinger.)

The attorney I work for represented (and still does represent) Jason Baldwin during the final stages of the case. I met Jason recently when he was stopping through San Francisco with his girlfriend. You would never suspect that this unassuming, polite guy had been through that nightmare.

It’s really scary when you think about how many other innocent people out there have been treated similarly, but without the benefit of a documentary and celebrity support, they’re stuck living with miscarriage of justice.

Exactly. These two movies mark huge exceptions. What luck to have a brilliant documentary made about your case. Imagine how many people are still in prison for crimes they didn’t commit, or worse yet, were executed.