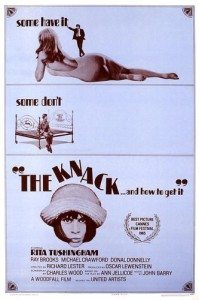

Nobody ever told me about Getting Away With It, a ’99 book in which Steven Soderbergh interviews Richard Lester, director of such movies as A Hard Day’s Night, Help!, Petulia, The Knack…And How To Get It, How I Won The War, The Bed-Sitting Room, and Superman 2 & 3, the full title of which book is: Getting Away With It, Or: The Further Adventures of The Luckiest Bastard You Ever Saw, Starring Steven Soderbergh, Also Starring Richard Lester As The man Who Knew More Than He Was Asked.

I found it all by my lonesome. Fourteen years after it was published, yes, and I had to buy it used because it’s out of print, but to sum up what follows: it’s worth reading.

Part I: Soderbergh

Turns out Steven Soderbergh, a director whose movies we love watching here at Mind Control, even if we don’t think they always work, is a neurotic workaholic. Which isn’t especially surprising. But it’s interesting to read his first-hand account of such. Because intercut, shall we say, with the Richard Lester interviews that make up maybe two thirds of the book are excerpts from Soderbergh’s diary of the time, which time was mainly ’96 and ’97, well before he became the bankable director of such big movies as Ocean’s 11, Traffic, and Erin Brokovich.

At the time, he was struggling to find anyone to distribute his just finished film, Schizopolis, and putting the finishing touches on Gray’s Anatomy, his film of one of Spalding Gray’s monologues. He also directed a play during this period, produced his friend Gary Ross’s movie, Pleasantville, and wrote, or, as is made clear, struggles to write, an adaptation of the kids book Toots And The Upside Down House for stop-motion director Henry Selick, and an improved version of Mimic for Guillermo Del Toro. As it would turn out, his work on Mimic wasn’t used (at least not enough for him to be credited), and Toots was never made.

Soderbergh is pretty funny in these diary-interludes, very self-deprecating in a “why would anyone pay me to do anything?” kind of way, complete with post-modern David Foster Wallace-esque footnotes commenting on his commentary, which today, so long from when it was written, is fairly charming. Might have been a little more irritating at the time. His struggles with studios, both to find distribution for his movies, and to get himself hired to do anything else, are illuminating. Not that we didn’t already know how Hollywood works, but first-hand accounts from the trenches are always enlightening. And funny when they’re not happening to you.

It’s at the very end of the book that Soderbergh, desperate to find anything to direct, gets hired for Out of Sight (after almost ending up making Charlie Kaufman’s script, Human Nature, which Michel Gondry ended up doing (he adds that he would have wanted to do Being John Malkovich, but it was already being developed)). Which gives the book another compelling angle, that of seeing the thought process of a young director of little-seen (aside from his debut, Sex, Lies, and Videotape) indie movies immediately prior to his becoming a director of bigger budget, far more popular Hollywood movies (as well as continuing to make the smaller, weirder flicks).

Soderbergh has since retired, supposedly, and become even more disenchanted with the workings of Hollywood than he was at the time of this book. But I don’t know. I expect he’ll be back directing feature films soon enough. The man can’t stop working.

Part II: Lester

The point of the book is to interview Richard Lester. Soderbergh thinks he’s an under-rated director, despite being a huge name in the ‘60s, and even considers his own crazy-ass Schizopolis as being directly inspired by Lester’s work in that era (Schizopolis, by the way, being a Mind Control favorite all humans are advised to see).

And it’s true, today as in ’99, Lester is not found in many conversations on great directors. If he’s mentioned at all, it’s in the context of either The Beatles or Superman, in the first case favorably, in the second, not so much. Why the love from Soderbergh?

In the ‘60s, Lester was on the cutting edge of movies. His films, though popular at the time, were highly experimental, told almost haphazardly, with wild editing and full of purely cinematic ways of expressing ideas. He never had much in the way of budgets, and was far from a planner. Lester liked to work quickly, often deciding what to shoot and how to shoot it on the fly. He worked most often with screenwriter Charles Wood, whose writing was as fractured and off-kilter as the resulting movies suggest. Lester had a way of deconstructing movies within his movies, a method that obviously found new favor in the ‘90s in the literary world, with David Foster Wallace and Dave Eggers, to name but two, a world this very book shows Soderbergh feels very much at home in.

The Knack, Lester’s third feature, following Mouse on The Moon and A Hard Day’s Night, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in ’65.

Part III: The Knack…And How To Get It

The knack, for those of you unfamiliar with ‘60s British slang, refers to one’s ability to score with the ladies. The movie is based on a play by Ann Jellicoe which Lester and writer Wood reworked drastically. It’s centered around a dopey guy, Colin (Michael Crawford), unable to score with anyone, and his upstairs neighbor, Tolan (Ray Brooks), who’s the slickest ‘60s player you ever succumbed to.

I didn’t know a damn thing about this movie when I sat down to watch it last week. It begins with a brilliant visual metaphor, showing an endless line of almost identical, beautiful women lined up on an apartment building staircase, shot from all kinds of strange angles, going into one room, passing by another, and okay, it sounds obvious writing it out like this, but the way it’s shot and edited, it takes a bit to realize what you’re watching. It’s not a dream, and it’s not real, it’s merely a visual metaphor for Tolan’s ability to score with countless women and Colin’s inability to score with even one.

Ask yourself this: how many movies have you seen lately that open with lengthy visual metaphors? I can tell you right now: none. Because, again, what’s shown isn’t even in the ‘world’ of the movie. It’s not really happening and it’s not specifically any character’s vision or dream or desire. It’s just a uniquely presented visual metaphor, of a kind you couldn’t accomplish in anything but film.

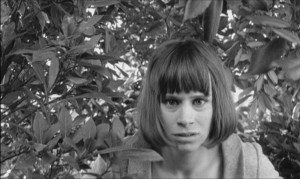

After that, the movie settles down to its almost unbearably manic pace. This is one weird movie. The dialogue is very theatrical and delivered rapidly amidst the rapid cuts. The other major characters are Nancy, a farm girl newly arrived in the big city, played by Rita Tushingman with wide-eyed innocence, and Tom (Donal Donnelly), a totally inexplicable Irishman who’s obsessed with painting walls white. His job is to expound on the emptiness of Tolan’s pursuits.

Kicked out of his last apartment for painting everything, Tom winds up at Colin’s flat, where he just kind of movies himself in and starts painting. Nobody seems to mind.

Tolan tries to help Colin find a woman. It doesn’t go well. Then Nancy turns up, Tolan makes a disgustingly lascivious play for her, and everybody makes Colin crawl around on all fours with a bag on his head pretending he’s a lion.

Eventually, in a park, Tolan appears to take advantage of Nancy. Indeed he must have, because she spends the next ten minutes saying, yelling, singing, “Rape!”, much to everyone’s consternation. Tolan is shown to be the weak, scared little man that he is, and you might be able to guess who Nancy ends up with.

The movie goes about tearing down the notion of what is to be a hip ‘60s swinger. It contains what might be thought of as two Greek choruses, one the voiceover voices of people our heroes pass in the street, an older generation, mumbling about these damn kids and their craziness, the other consisting of Colin’s classroom of gradeschool kids, who are intercut at various times repeating whatever Colin says, just like the good little students they are. Okay, I’m not entirely sure about the symbolism here, but it sure is odd and entertaining. And funny. Soderbergh says he desperately wanted to steal the school kids bit for one of his movies, but decided against it.

The Knack is shot in black & white by David Watkin and it’s lovely throughout. Black & white used to look so great. What happened? Different film, different lenses. Soderbergh spends a fair amount of time talking to Lester about film tech, Soderbergh being a bit of nut for old lenses.

The Knack has not necessarily aged well. It’s very much of its time in terms of characters and attitude. Which isn’t to say it’s bad; I enjoyed it. It’s just—hard to watch, in a way. It’s entirely possible that, should you watch it, you will wig out well before it’s over and turn the damn thing off. But dammit, it’s brilliantly experimental in a way filmmakers seem to have given up on as early as the ‘70s.

Part IV: More Lester

Lester made what he and star John Lennon called an “anti-anti-war movie”, How I Won The War (’67), which I’ve yet to see (not easy to dig up on DVD). As Lester puts it, most war movies were either about so-called “good” wars or “bad” ones. What he and Lennon wanted to show was that war as a concept is itself bankrupt. They intended to show the absurdity of war, no matter the context. It’s set during WWII, but is clearly meant to comment on the then heating up “conflict” in Vietnam.

This all sounds like a great idea, though maybe Lester forgot about Kubrick in his estimation of war films? If anyone made abundantly clear the pure absurdity of war, it was Kubrick, in both Paths of Glory (’57) and Dr. Strangelove (’64).

Lester also made the totally bizarre ’68 post-nuclear-apocalypse movie, The Bed-Sitting Room, which I saw recently and wrote about here. In short, it’s one weird-ass movie, and another example of Lester’s willingness to leap into the unknown.

Lester says that he began to feel less connected to current culture as time wore on, and so felt less able to comment on it as he’d done in the ‘60s. This led to him working in historical genres in the ’70s with The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers, Royal Flash, and Robin And Marion. Plus he made the action flick Juggernaut (’74). I have seen none of these. Not movies anyone talks about today. But I’m now very curious.

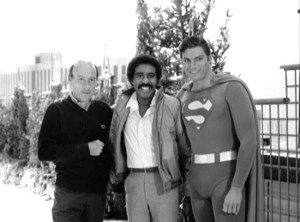

Then came the whole Superman brouhaha. Lester was a producer of the first one, during which some of the second was filmed, but director Richard Donner and the Salkinds, who financed the movies, hated one another. Lester was brought on to finish Superman II without Donner’s knowledge, everyone hated everyone else, and it was all something of a giant clusterfuck. Lester says the parts of Superman II he liked directing best were the simple human scenes between Clark and Lois, scenes he could direct in the loose style he enjoyed, unhampered by the constraints of special effects.

In ’89, while directing The Return of The Musketeers, actor and close friend of Lester’s, Roy Kinnear, fell off a horse, and sustained injuries leading to this death. Lester finished the movie, and retired after that. The death hit him hard. Reading these interviews, he doesn’t sound like he’s up for ever directing anything else. The world has passed him by, he feels, in large part because he very consciously let it.

Part V: Atheism and Evolution and The End

The weirdest part of the book is when Soderbergh starts talking about evolution. He does so because Lester is an outspoken atheist (this was in ’97, well before the more recent boom in outspoken atheists). Soderbergh appears to be at least agnostic, but as he yammers about his confusion regarding the universe, he reveals such an astounding ignorance of the most basic elements of natural selection that I felt a deep sadness for the world. If someone as bright as Soderbergh can be this clueless, can spout such daffiness on the subject, what hope is there for the rest of the world?

The book has no ending. The interviews stop. Soderbergh is hired to direct Out of Sight, and leaves us with his hope that he can get this movie Erin Brokovich made (spoiler alert: he does).

It’s Soderbergh’s hope that his little book ignites an interest in Lester’s movies. He sums up Lester’s output thus:

After all, the man made, in my opinion, three Masterpieces (A Hard Day’s Night, The Knack, Petulia), four Classics (The Three Musketeers, The Four Musketeers, Juggernaut, Robin And Marion), six worthwhile divertissements (It’s Trad, Dad, Help!, A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum, Royal Flash, The Ritz, Superman 2 and 3), and three Really Fascinating Films That Get Better With Age (How I Won The War, The Bed-Sitting Room, Cuba).

It’s a nice little read, this book, of interest to you who are film nerds, and likely no one else.

interesting. Petulia is a weird flick and neither as good nor as bad as you might suspect. i remember seeing A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum ages ago and thinking it was very funny. A straightforward 60s farce with Zero Mostel, who is just the funniest man who ever lived.

Lester: “You can’t say that Paths of Glory is an anti-war film. It makes it quite clear that if we’d had Kirk Douglas leading the troops in the first place we’d all have been able to get out there and kill Germans more efficiently.” The movie is parodied in a line in How I Won the War: “What we want is more human killers!”

I think that’s a bit of a shallow reading of Paths of Glory. The point of the movie is not that, in this one instance, a few bad apples acted crazy, and that if they’d listened to Kirk, all would be well and more Germans could be killed. Kubrick’s point is that war is itself insane and absurd. Kirk is the audience surrogate, and through him we watch it all and scream, “What?! That’s insane!” of every other character in it.

It’s not a matter of saying, well, if Kirk was in charge, we could fight better. It’s that there is no sanity in war. A man like Kirk can’t be in charge, because war is by definition absurd and dehumanizing. A sane man waging a war is, by Kubrick’s definition, impossible.

I think either reading is possible.

In fact, the generals, though heartless and evil, have sane motivations that make sense to them. They simply rate the lives of the men lower than Douglas does. He has command of a unit and is shown as sane and humane, concerned with winning the war as best he can.

Can Kubrick’s apparent hatred of war be squared with his enthusiasm for Napoleon? I think a case could be strongly made that what he hates is incompetence and sloppy politicking.

But the generals aren’t simply heartless and evil. They’re farcical. Not quite as extreme as Jack D. Ripper, but close.

Kubrick found Napoleon fascinating as a person and a character. Napoleon certainly got things done. Does that mean Kubrick approves of what he did?

Looking at Strangelove and Full Metal Jacket, I have a hard time seeing the argument that Kubrick thought war was anything but an absurd, murderous farce, one necessarily dehumanizing to all who partake in it.

It’s one thing to note that the people who wage war in his films are–at a minimum–incompetent, but to say the only meaning in his war films is a critique of incompetence seems awfully limited and ignores everything else going on in them.

I should add that I am a huge admirer of Paths of Glory. But there’s an absolutely consistent theme in Kubrick which deals with human folly and capacity for error. He doesn’t tend to attack the nature of the task, whether it’s the Viet Nam war or space travel or crime control, he focuses on how it’s achieved and what mistakes are made.

I wrote the above before seeing this.

Yes, that is indeed a consistent theme. But I think that his war films have more going on in them. I think he is certainly attacking the task of war. In Glory, war is dehumanizing. In Strangelove, it is a mad farce. In Jacket, the first half is about dehumanization, the second about children murdering children.