Stephen King has a new book out, a sequel to The Shining, titled Doctor Sleep, chronicling the further adventures of the boy with the shine, Danny Torrance. No surprise, then, that doing interviews to promote it (because lord knows King needs all the press he can get to insure that someone, anyone, buys even one of his little-read novels), he’s been asked once again to opine on Kubrick’s movie version of The Shining, which movie King has long been on record as loathing.

Has King changed his tune? Not at all. He still thinks the movie is cold, distancing, misogynistic, not about the characters he invented, poorly directed, and not scary.

Check out what King had to say about Kubrick’s movie when he was asked about it in ’83:

From a plotting level, I don’t think the film works very well, and in terms of execution I think some of the choices that he made about where to set his cameras and how to shoot certain scenes were amazingly bad. And I know that it must sound…not just pretentious but downright…almost arrogant for me to say that because he’s a great film-maker and I’ve never even…you know, yelled ‘cut’ at the end of a scene or anything. And it is pretentious, it is arrogant, and yet from the standpoint of film-goer…any film-goer who’s seen enough films turns into a film critic, even if it’s only in their own mind.

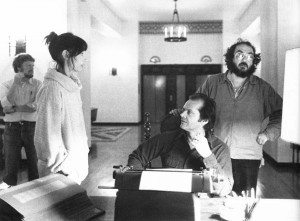

Well, yes, to say that Kubrick, of all directors, made “amazingly bad” choices about how to film scenes is a bit arrogant. But then again, it’s true that one need not be a filmmaker to critique films. What’s an example, King? How about when Wendy finds the pages and pages of “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” a scene invented by Kubrick? What’s wrong with how that’s shot?

And then for some reason, some perverse reason that I don’t even understand, he draws away and we see Nicholson coming up behind her. And his line is great; he just looks at her and he says ‘How do ya like it?’ And you know at that point, if you didn’t know before, that the man is utterly out of his gourd. But why in the world he wanted to draw away and show us that, to allow us to see him before she saw him, I don’t know. It’s a mistake that a freshman director wouldn’t make; it’s certainly not the way Kubrick would have shot the scene twenty years ago.

Reasonable people may disagree. The hotel is watching her, King, through the eyes of Jack. It is to me a perfectly shot scene, a perfectly scary scene. Kubrick cuts from Wendy looking at the pages to Jack’s POV coming from behind a wall to see her back. It is, in a word, scary. You’re already scared to death seeing those pages, and then to see that Jack’s watching her all along? Your heart stops in that scene.

I don’t think King has ever understood film particularly well. He’s not known for being a screenwriter (note from my 11 year old self: “Creepshow is awesome!”), nor directing, unless you happen to think Maximum Overdrive (’86) is well directed. Which you don’t. King is very literal in his interpretation of film. He doesn’t seem to grasp the power of images to convey inner thoughts and emotions and states of being, something Kubrick does so well, especially in The Shining. A short-hand must be used in film. A single image may convey the depth of what in a book, particularly one written by the notably verbose King, may take a whole chapter to explain.

King wrote a mini-series version of The Shining in ’97 in order to more faithfully bring his book to the screen. It is something of a disaster.

The heart of the matter is that King loves his book, he loves the characters, and he doesn’t like the way Kubrick went about changing them. This is all entirely understandable. It’s a personal book to King. Jack Torrance may be his most autobiographical character.

As a kid, I loved King. I read everything he wrote up until the early ‘90s or so. I always thought The Shining was his best. It was great, the movie was great, they were two very different animals, as they should be. Or so I would say.

Then, last week, after reading this article in Salon that argues for the validity of King’s point of view, I re-read The Shining for the first sime since the ‘80s. Bad move.

The book has not aged well. It’s not bad. It’s standard King. Decent characters, an intriguing story, some good suspense and creepy notions, but way too wordy and digressive. It feels like it wants to be an allegory for alcoholism and domestic violence, but then the supernatural is put front and center, and there’s nothing left but a demonic hotel out for blood.

I love that Laura Miller in the Salon article says King’s writing “contains a shambolic bagginess.” Wow. Does it really? So that translates into, what? Sloppiness? Yes, I think that’s the word. And Kubrick, she tells us, is a “meticulous stylist” with no humanity. A popular opinion among those lacking the patience to actually watch and think about Kubrick’s films. How anyone could watch his films and not see the humanity in them is beyond me. As for The Shining feeling cold? It takes place in the mountains of Colorado. In the winter. In the snow! Of course it’s cold! The characters are isolated in a frozen landscape. Jack is not feeling warm thoughts toward his wife and son, to say the least.

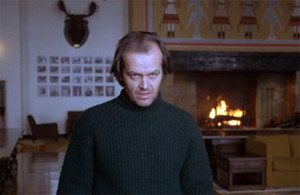

One of King’s biggest complaints is that Jack Torrance as played by Jack Nicholson seems crazy from the start. You know immediately that he’s going to go nuts and do something horrible. Whereas in the book, Jack Torrance is an alcoholic everyman who is slowly but surely driven mad.

I understand that King has his own perceptions of the character he wrote, but I just read the book, and Torrance is a nut in the book from the start. The first scene of the book, like the movie, features Overlook manager Stuart Ullman telling Jack about an earlier caretaker, Grady, who hacked up his daughters with an axe and shot himself and his wife. There is no mystery as to what’s going to happen in this story.

All during this first chapter, and every subsequent one, Jack obsesses over the time he drunkenly broke Danny’s arm, and the time he almost beat to death a college student, the woe his wife Wendy has caused him, and on and on. His obsessions are realistic, certainly. You believe this character. You believe, from the start, that if anyone’s going to go stir-crazy and beat his family to death, it’s this guy. King paints him as totally unhinged, waiting for any little push over the edge.

Kubrick does the same thing. I was actually surprised reading the book just how faithful Kubrick is. It’s as though Kubrick saw inside the book, saw through the wordiness, saw through the parts that don’t work, and pulled out the essence of the story for his film. Which essence, obviously, is not what King meant for his book to convey. But what an author means to do is often at odds with what he does.

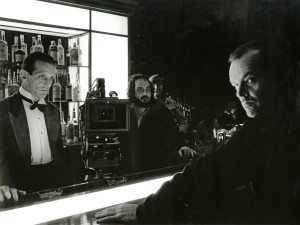

Here’s Kubrick on the adaptation:

With The Shining, the problem was to extract the essential plot and to re-invent the sections of the story that were weak. The characters needed to be developed a bit differently than they were in the novel. It is in the pruning down phase that the undoing of great novels usually occurs because so much of what is good about them has to do with the fineness of the writing, the insight of the author and often the density of the story. But The Shining was a different matter. Its virtues lay almost entirely in the plot, and it didn’t prove to be very much of a problem to adapt it into the screenplay form … To be honest, the end of the book seemed a bit hackneyed to me and not very interesting. I wanted an ending which the audience could not anticipate. In the film, they think Hallorann is going to save Wendy and Danny. When he is killed they fear the worst. Surely, they fear, there is no way now for Wendy and Danny to escape. The maze ending may have suggested itself from the animal topiary scenes in the novel. I don’t actually remember how the idea first came about.

The ending of the book (book spoiler!) hinges on the boiler in the basement of the hotel. It’s old and the pressure builds up such that Jack has to “dump” the pressure off twice a day so the thing doesn’t explode. Which is to say, you know how the story’s going to end from the very start. Jack, totally consumed by the hotel, forgets to dump the boiler. The hotel explodes. Danny, Wendy, and Hallorann escape.

I think Kubrick’s ending is far more powerful. Danny outwitting Jack in the hedge maze is more satisfying than his “remembering” the boiler and telling the monster his father has become about it. How could the hotel itself have “forgotten” that most important part of “itself”? Seems like a massive logical hole in the book.

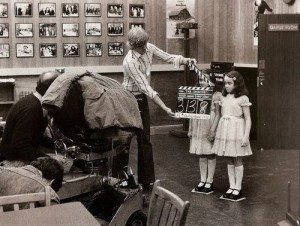

King calls the Wendy of the movie, in the BBC interview where all this latest hubbub began, “one of the most misogynistic characters ever put on film.” As though the Wendy of the book is much different. Once again, as with Nicholson, King seems to be basing this on seeing actors as opposed to writing about characters. Wendy in the book is just as terrified of Jack as Wendy in the movie. Both Wendys use kitchen knives as their weapons. In the book, Jack actually pounds her with a roque mallet before she stabs him in the back, killing him. Imbued with the power of the hotel, he rises despite being dead, and terrorizes her and Danny until the hotel blows up. Wendy does nothing else in the book to save herself and Danny. Her only role in the book is to worry.

In the movie she’s presented as a much homelier character, as someone you can believe doesn’t have the strength of character to leave Jack. Says Kubrick of Shelley Duvall:

I think she brought an instantly believable characterization to her part. The novel pictures her as a much more self-reliant and attractive woman, but these qualities make you wonder why she has put up with Jack for so long. Shelley seemed to be exactly the kind of woman that would marry Jack and be stuck with him. The wonderful thing about Shelley is her eccentric quality — the way she talks, the way she moves, the way her nervous system is put together.

Bizarrely, the Salon article calls alcohol “incidental” in the film, another indicator that the author simply isn’t paying attention. In the wordy book, Jack’s desperation for a drink—he’s been on the wagon for a little over a year—is discussed on virtually every page. It’s what defines him.

Alcohol isn’t brought up in every scene of the movie because that’s not how movies work. You have to pay attention in a skillfully made movie. Jack drinks in the movie at a very specific moment, and when he does, everything changes. He meets Grady and is given his instructions: kill his family.

Kubrick is a master of adaptations because he understands that there’s no sense in being “true” to the source material. What matters is making a movie that works on its own terms. Books and movies tell stories in very different ways. To forget this, to try to literally “visualize” a book, is to end up with a movie that’s dead on arrival.

For example, in the book, Danny has numerous visions of what’s to come at the Overlook, prime among them one where a shadowy figure lopes down a hallway swinging a bloody roque mallet, crying out, “Come and take your medicine!” Scary enough, and of course it’s a vision of the end of the book, when Jack will be revealed (surprise!) to be that shadowy character. In the movie, Danny has but one vision of the future: the elevator opening to let out an ocean of blood. This works because this weird, hallucinatory image stands in for “vast and inexplicable horrors to come,” exactly what Danny will have to face. It’s a cinematic way to visualize Danny’s nebulous visions. It sticks with the audience, that’s for damn sure. It’s representative of horrors–left to us to imagine.

The ideal adaptation sees one artist using another’s work as inspiration. What point in trying to copy it outright? It amazes me that people would want a book translated on-screen identically. To what end? You’ve already got the book. It’s not going anywhere. It’s not being changed. Imagine if a writer said, “I’m going to re-write The Shining! I’ll do my best to be faithful.” The only way such a thing could be interesting is if the new author wrote the story in their own way, with their own language, their own obsessions, their own interpretation. The same goes for movies. The best adaptations represent artists in their own right telling their own versions of a story.

Is there something to the notion that King’s ego is, in some small way, bruised? After all, the movie version of The Shining contains some of the most iconic scenes and images in the history of film. It’s stature has only grown with time. It’s made by a master director. Whereas the book is never going to find its way on to any list of greats. It would have to bug King a little bit that when people think of The Shining–his story, his characters—they picture the movie.

So in the end, King’s dislike of the movie is understandable. He will never be able to see the beauty of Kubrick’s version of The Shining. He may think he has logical reasons for disliking it, but he does not. His reasons are deeply personal. The rest of us are the lucky ones. We get to go on loving the movie for what it is: one hell of a good horror flick.

Funny coincidence. I also went through a King phase in the late 80s, starting when I was 14. I devoured everything he published up until 1990. Then I swiftly lost interest. The Shining was the first I read, and was always one of my favorites, but I think once was enough.

It’s a little sad that King can’t appreciate Kubrick’s film. Like the scene when Jack finds Wendy reading his “book.” King thinks it was a missed opportunity to shock the audience. It reminds of something King once said about using gore in his fiction. He basically said that it was the last resort because it was too easy, that he would try to scare and disturb his reader every possible way, but that sometimes he will go for the easy gross out. He should have known that the same applies to horror films: cheap scares are easy. Building up dread takes more work. How could he not realize that’s what Kubrick was doing? It must be because he could not watch the film with open eyes.

Oh yeah, the passage is from Dance Macabre. I can’t find the whole passage online, but here are oft-quoted excerpts: “The 3 types of terror: The Gross-out: the sight of a severed head tumbling down a flight of stairs, it’s when the lights go out and something green and slimy splatters against your arm. The Horror: the unnatural, spiders the size of bears, the dead waking up and walking around, it’s when the lights go out and something with claws grabs you by the arm. And the last and worst one: Terror, when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute. It’s when the lights go out and you feel something behind you, you hear it, you feel its breath against your ear, but when you turn around, there’s nothing there.” And, “I recognize terror as the finest emotion and so I will try to terrorize the reader. But if I find that I cannot terrify, I will try to horrify, and if I find that I cannot horrify, I’ll go for the gross-out. I’m not proud.”

“I’m not proud.” Well, there you go. King wrote a book about ten years ago on his writing method, which is: he has an idea, and he starts writing, with no ending in mind. When he gets to the end, he goes over everything once, and presto! A book. He’s a guy at a campfire telling a scary story. Not a bad thing at all, but probably best when you’re a kid.

What always made the moment where Wendy discovers the writing so chilling for me is that as the camera moves from behind the pillar we see Wendy’s back from what we think is Jack’s POV, until Jack himself slides into the frame and we also see his back. It’s the hotel watching, not just Jack; if it were just Jack’s perspective we wouldn’t see him from behind sliding into the frame. It’s a small, subtle moment that gives the hotel a presence, a set of eyes, and a creepy as hell voyeuristic personality. I love both the book and film, but for different reasons. I can imagine it being difficult for King to give up emotional ownership of what he loves about his own book, but the film has an aura and brilliance all its own.

Good observation. Somehow I imagined I’d said the same thing, but nope. I sure didn’t. The hotel is always watching. What a great movie.