You’re dying. In twenty years, or in six months, or on this coming Wednesday you’re going to die. Whichever it is; there’s no escape. So what are you doing with the time you’ve got left?

Do you even know?

Normally Mind Control Double Features pair complementary films. Not this week, you poor poor dying person. This week we’re going to contrast in almost every possible way. We hope the resulting effect twists your head around like a owl’s and makes the inevitability of your impending death that much more undeniable.

Because you’re dying. Right now! Or any day, at least. Tomorrow? Yes. Probably tomorrow.

In case you do survive long enough to watch these two films, you will notice that they are starkly different in genre, in period, in style, and — at first glance — in terms of their content.

They fit together perfectly.

Ikiru (1952)

Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru (meaning ‘to live’) tells the story of a calcified bureaucrat. With his wife dead, his son grown and married and self-absorbed, and his job a rote repetition, it is unclear — to this mummified man or to anyone else — what his days are good for. He has not even seriously considered the question for years.

Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru (meaning ‘to live’) tells the story of a calcified bureaucrat. With his wife dead, his son grown and married and self-absorbed, and his job a rote repetition, it is unclear — to this mummified man or to anyone else — what his days are good for. He has not even seriously considered the question for years.

Then he learns that he has stomach cancer and will die within half a year. Just like you.

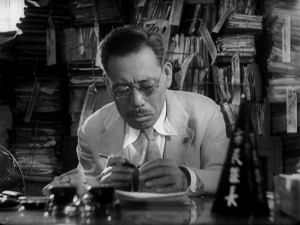

Our civil servant, Kanji Watanabe (Takashi Shimura), is suddenly forced to confront the waste of his life. But phrasing it in that way isn’t quite accurate. It doesn’t feel like Watanabe’s life has been wasted, for his life thus far has not been comprised of precious substance. Life itself is not precious. Instead, what Watanabe discovers is that he has wasted his meaning. He has had plenty of days wielding his official stamp, and caring for his son, and sitting at his desk but long ago he let the vibrancy and urgency bleed from it all.

He had a life; he just forgot to pay attention to it.

Ikiru is the investigation of Watanabe’s reawakening and his death. Like many Kurosawa films, its trajectory follows a meandering path, concerned more with a character’s progression than with dramatic events. Like many Kurosawa films, it is affecting and poignant and beautiful. Ikiru is frequently visually arresting and clever.

Imagine yourself in old Watanabe’s shoes. Maybe that’s easy — maybe your life has long ago been bled of urgency and intention. And now, definitively, you are told you will die. (Psst. You will die.) What is it that you do with the opportunity you have left? What meaning can you muster from your remaining life?

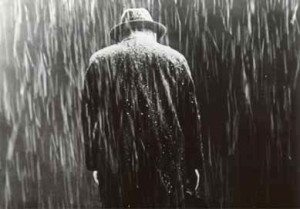

In Ikiru, petty things first attract our doomed bureaucrat’s attention. He lets his job twist. He immerses himself in pleasures, spending his hoarded yen, seeking the company of the young and vivacious. Then, after most films have ended, this one surprises you with its beginning. At what should be the end of its life, Ikiru finally comes to terms with what it must be and refuses to be anything but that. Even when death itself refuses to delay, Watanabe and Ikiru press quietly on.

The film’s structure here confounds your expectation. Effectively, it makes you reconsider Watanabe, what a man like him can be, and what an individual such as yourself can be. Whether that eventuality is likely or not. Whether a soul realizes it in time or doesn’t.

You will watch Ikiru and experience Watanabe’s tardy awakening. Like the other characters in the film, you will refuse to see or abashedly accept the insistence his focused awareness allowed him. And then, most likely, you will forget Watanabe. You will forget the lesson you learned through him and you will roll slowly back down the hill to the shallow divot of your existence.

Then, someday perhaps, someone will tell you how long you have left. And, even if it kills you, you will try to wring the meaning from your life. If it’s the last thing you ever do.

Into the Abyss; a Tale of Death and Life (2011)

I would be hard pressed to find a film that, on the surface, feels more estranged from Ikiru.

I would be hard pressed to find a film that, on the surface, feels more estranged from Ikiru.

Werner Herzog’s documentary Into the Abyss purports to be about the death penalty, focusing on a depressingly pointless triple murder committed at the beginning of this century in Texas. Herzog interviews the victims’ families, the two young men who were convicted of the crimes, and others whose lives brushed against theirs.

This film is only superficially about the death penalty, though. It is really about how we waste our lives, but to phrase it that way is not quite accurate. It is more about our lack of intention. It is about how we stumble through our lives unaware of what they are until it is too late to do anything about it.

Only a death sentence — and sometimes not even that — can rouse us from the inertia that depresses us into the comfortable crevasses of society.

Watching Into the Abyss, at first I was lulled. This film is no Thin Blue Line or Paradise Lost, in which innocents are railroaded by perverted justice. Herzog does not seem to even really care if Michael Perry and Jason Burkett really murdered three people because they coveted their car. Both boys variously imply their innocence and admit their guilt and smile and repent and forgive.

It was only as the documentary progressed and Herzog dragged me off on tangents to meet the people who cosset and crowd these boys that its actual intent becomes clear.

The one thing that almost no one in Into the Abyss does at any time is inhabit their lives. Yes, there are moments of genuine grief and contrition. Many people voice regret and pine for opportunities squandered. Only at the end, though, does anyone demonstrate that they understand in any way that it is the potential intention of their lives that they have wasted, as opposed to just another day.

In the face of tragedy and in the face of callousness and in the face of love, these people consistently reject the chance to truly look at themselves and choose their own direction with awareness.

About the film, Herzog says:

This is not an issue film; it’s not an activist film against capital punishment… it’s not the main purpose of the film.

Because Into the Abyss is not about life being precious. On the contrary, life is ubiquitous. You literally cannot throw a rock without hitting something alive — person, mouse, grass, paramecium, whatever. What is precious is each moment of life lived in awareness, with intention.

You can have a life like that. All you need to do is wake up.

And you should, even if it’s the last thing you ever do.

I saw Ikiru recently on Turner Classic Movies. God, I love Turner Classic Movies. It is a beautiful and stirring film. It’s amazing how good cinematography can make a drab office look interesting.

Now, pardon, I have to go smell some roses.

For me, it was that last act — where it all just jumps ahead and takes you out of his POV and into everyone else’s. This is how Watanabe appears to the drones: crazy and sad. And yet, when he’s gone, they see he did something no one else dreamed possible. That’s not building the park, but being content to go, satisfied with his life.

I saw Ikiru years ago. I need to watch that one again. I liked Into The Abyss too, but then I like all things Herzog. All of his movies go below the surface. They’re all asking why people do what they do, and what it means to be human.

I think you’ll appreciate a re-watching of Ikiru. It really does make a surprising companion for Abyss.

Reads like the ultimate Yom Kippur sermon. Excellent.

You should watch this double feature, Dad. I think you’d really get a lot out of it.