There are two kinds of movies about high school. Those set in the present, in which a harsh light is blasted onto the horrible nightmare of youth, and those set in the past, in which high school, whatever its short-comings, is remembered as magically sweet and life-changing.

I wrote about two of the former recently, The Blackboard Jungle and Class of 1984, movies made by adults who, nostalgic for their own dreamily profound teenage years, saw around them a modern high school hellscape turning children into monsters. Look at the horrors today’s teens must face!, they seem to be shouting, save them before it’s too late!

In a similar vein are movies like Heathers and Mean Girls, made by film-makers only obliquely nostalgic for their high school days. For them, high school sucked, but hey, now they’re making movies, things worked out pretty good, and with a sense of humor they can look back and show the horrors of high school in an amusing light. Or a light in which you murder all those kids you hated most at the time. Movie revenge! The sweetest kind.

High school movies set in the past, however, are inevitably aglow with the warm light of nostalgia. They are a response to the terrible life today’s teens must lead, whenever “today” is. Everything always sucks in the present. Everything was always grand in the past. Remember when you were young? How fresh and innocent the world was? How it was filled with wonder and hope? Now look at! It’s all turned to shit and Clorox bottles, and Lake Erie is filled with giant, man-eating lampreys. For example.

In this week’s Mind Control Double Feature, we get nostalgic for high school movie nostalgia. We’ll go back 40 years to the ‘70s to remember the ‘60s, then ahead 20 years to the ‘90s to remember the ‘70s. So sit back, close your eyes, and remember how sweet life was when you were young. Only then open your eyes; there’s movies to watch.

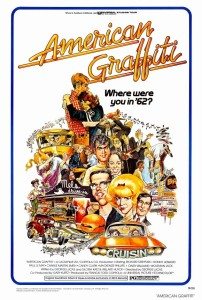

American Graffiti (’73)

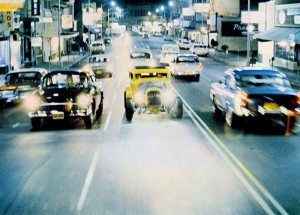

Long before George Lucas turned into a 900 pound lizard-monster biting off the heads of anyone dumb enough to have enjoyed his movies, and doing worse still to those who didn’t, he made American Graffiti, a movie meant to evoke his teen years growing up in Modesto, California, where he spent his nights cruising in cool cars up and down the main drag, and racing them on the backroads.

The story goes that after making his weird, depressing, sci-fi debut, THX 1138, Coppola dared Lucas to make a commercial movie. It took a number of screenwriters and a number of years, but American Graffiti was the result.

At first no studio wanted it. Universal eventually agreed to fund it, but didn’t like the end result. They were going to put it out as a TV movie. Wiser heads prevailed when word of mouth began to spread. They upped the ad budget, released it, and struck gold. American Graffiti remains one of the most profitable films ever made (when comparing budget to profits).

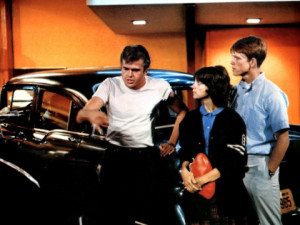

It’s got the now-prototypical story device of following a bunch of teens around over a single night, the night before graduation. There they sit, perched on the knife edge separating past from future, childhood from adulthood. What will they do on their last night as carefree kids? They will have good times, hard times, make decisions, some foolish, others wise, and come out better people, changed people, in the morning. Awww…

American Graffiti is set in ’62. The kids are played by Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, Paul Le Mat, Charles Martin Smith, Candy Clark, Mackenzie Philips, Cindy Williams, and still others, including Harrison Ford as the older Bob Falfa, and Wolfman Jack as himself, spinning records all night long.

The music followed the model set by Easy Rider: no score, just rock ‘n roll songs, different ones for almost every scene.

There’s no story that needs relating here. The question for each of the characters is: what will they do next? And more immediately: what will they do tonight? Will they join the “punk” gang? Will they race against Falfa? Will they find the mysterious dream girl (Suzanne Somers) in the white Ford Thunderbird? Will they get rid of the annoying freshman girl? Will they stay with their sweethearts? Break up with their sweethearts? Live forever in their dead-end town? Go to college and an unknown future? Dance?

American Graffiti is sweet and funny little movie. Made in the early ‘70s, an era of dashed ‘60s dreams, exceptionally corrupt politicians, endless war, and dark, soul-searching movies reflecting it all, American Graffiti was a rare beam of light. It’s frankly amazing that George Lucas made it. I guess the money and cynicism hadn’t yet eaten away his soul.

Only hold on a second. If everyone, once grown up, is nostalgic for their childhood, then mustn’t the ‘70s have been just as glowing, innocent and romantic as ’62? I’m glad you asked that. Next up:

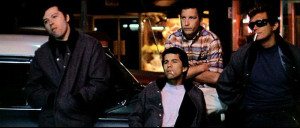

Dazed And Confused (’93)

Twenty years after American Graffiti opened, Richard Linklater made his own one-night-in-the-life-of-high-school-kids movie, and when did he set it? In the magical days of his youth: 1976.

For Linklater, high school wasn’t about drag racing. It was about finding a party to hang out at and scoring Aerosmith tickets. Which is essentially the only story the movie has to offer. It’s enough.

The kids are played by a whole damn bunch of actors, many of them new to film, including Ben Affleck in one of his more believeable roles (an ass), Matthew McConaughey in one of his most memorable roles (with the best line of the movie; you’ll know it when you hear it), and Parkey Posey being all kinds of hilarious. Also showing up are Renée Zellweger, Nicky Katt, Milla Jovovich, Wiley Wiggins, and many more.

The movie starts on the last day of school. We follow two groups of kids: juniors on their way to becoming seniors, and eighth graders on their way to becoming freshman. Turns out many rituals between these groups existed in Texas in ’76, including the older boys making wooden paddles with which to beat and terrorize the younger ones. Fun times.

More importantly, everyone needs a party to go to. There is much beer drinking and dope smoking, plenty of the era’s rock songs on the soundtrack (though despite being called Dazed And Confused, Led Zeppelin refused the use of any of their songs), and all of the major characters get to experience one little character defining change over the course of the night.

I suppose you could call Dazed And Confused the stoner response to American Graffiti, because of both the behavior of the former’s characters and the style of its film-making. Linklater is a chill kind of director. His characters aren’t in any hurry to do anything, yet the story never drags. It’s funny in the way all the boring, stupid crap you did in high school is funny, and as meaningful too. Which when you’re in high school, it is all meaningful. To you, it’s all there is.

When this movie came out I saw it often. It told the tale of high school more truthfully than I, at age 22, had ever seen. Heathers was surely more outrageous, The Breakfast Club more archetypical, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off more what you wished it had been, but Dazed And Confused—that was the movie that told it like it was.

Couldn’t agree more about Dazed & Confused. There are so many little details they got right. Like the playing of that game with the folded up piece of paper in class–one kid flicking it with his middle finger, the other kid holding up his fingers as goal posts. Like the aimless driving around in cars. Like some of the stoned dialogue. Like the clothes (so many movies have tried so hard, but few have gotten it right.) Like the inclusion of shots of a pinball machine. Like the ugly cruelty of some of the kids to each other that would probably be forgotten by the perpetrators at night’s end, and the generous acts of kindness by others….

Yep. Both great films. And I think when done watching these two everyone should watch Freaks & Geeks.

Yes and also yes to all of those things you have both just said.